The current COVID-19 vaccines are no overnight sensation – they have been years in the making.

The current COVID-19 vaccines are no overnight sensation – they have been years in the making.

Dr Karl Gruber (PhD) reports

Despite a popular perception that COVID-19 vaccines were rushed through, in reality, they have been in a long-planned and carefully designed pipeline.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a human pathogenic coronavirus of zoonotic origin and was first reported in late December 2019 in Wuhan, Hubei province, China. The virus is the causative agent of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which claimed its first life in March 2020. A few months later, COVID-19 went global and proved to be one of the worst pandemics the world has faced in recent decades.

Today, more than 136 million people have been infected with the virus and nearly 3 million have died from the disease. The economic impact of the disease is enormous and continues to grow.

In the midst of the panic, fear, disease and death that COVID-19 is causing in many parts of the world, we have learned a lot about ourselves, our health care systems, our governments and our research capabilities.

One positive and perhaps the most amazing outcome of the pandemic has been the development of vaccines. Traditionally taking up to 10 years or more to develop, COVID-19 vaccines have been designed, tested and deployed within 12 months.

Today, 184 vaccine candidates are in pre-clinical development, nearly 100 are currently being tested in phase I, II or III clinical trials, and five vaccines are now widely available and being deployed worldwide. More than 754 million vaccines have been administered already and millions more are on the way.

The COVID-19 vaccine development process has been hailed as “a miracle of modern technology”, but in the minds of many, a lurking fear grows – that these vaccines were rushed into being, potentially sacrificing the safety of their users.

However, experts in vaccine development explain that nothing is further from the truth and while they have been made at an unprecedented pace, it hasn’t been at the expense of safety or efficacy.

Here is how it was done.

A not-so-new virus

A not-so-new virus

The COVID-19 virus is not an entirely new coronavirus – it has known relatives. In the past 10 years, two well-known coronaviruses made the jump from their animal host (bats, most likely) into humans. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) was first reported in the Guangdong province of China in 2002. The virus infected over 8,000 people across 29 countries, killing about 15% of those affected – an unusually high fatality rate.

Ten years later, in April 2012, we saw the emergence of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) coronavirus in Jordan. Since then, a total of 2574 laboratory-confirmed cases including 885 associated deaths have been reported globally with a staggering 34.4% fatality rate. MERS infections have continued to appear sporadically – the most recent laboratory-confirmed patients were reported in March 2020.

Coronaviruses are not the only viruses causing havoc among humans. Viruses such as Ebola, Marburg, Hendra, Nipah, or those causing influenza, have also led to significant morbidity and mortality around the world.

But an important outcome of these viral outbreaks has been their role as a warning agent. The clear risks and potential consequences of these zoonotic outbreaks made a mark on the mind of scientists as well as policy makers, who were shaken by the prospect of another, worse, global pandemic.

As a consequence, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness and Innovation or CEPI was founded five years ago.

Why CEPI matters

CEPI is a global partnership that brings together funding from public, private, philanthropic and civil society organisations. Their goal is to finance independent research projects that develop vaccines against emerging infectious diseases. It is backed by heavy players such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Wellcome Trust and the World Economic Forum. By June 2020, it announced raising more than $1.3 billion to support their COVID-19 efforts.

One of the first outputs of CEPI was to fund vaccine research programs against viruses such as MERS, Nipha, Chikungunya, Rift Valley fever and SARS-CoV-2. Since early 2018, CEPI has provided more than $200 million to fund vaccine development against Lassa fever/MERS-CoV.

Critically, it also provided more than $50 million for the development of new technologies in vaccine design. When COVID-19 came along, CEPI jumped into action.

“CEPI had effectively a competition. The competition was to come up with a vaccine technology platform that could develop a vaccine to a new virus within 16 weeks,” said Dr Norman Swan, host of the Coronacast podcast and the ABC Health Report.

Throughout 2020, five research groups received funding to develop vaccines against COVID-19. By June 2020, Clover Biopharmaceuticals had begun Phase I clinical trials in Perth to test the safety and immunogenicity of a protein-based vaccine candidate. This was the fifth CEPI-funded vaccine candidate reaching clinical trial testing.

CEPI has contributed to vaccines developed by Moderna Inc., Novavax Inc., University of Oxford and AstraZeneca, and Inovio, which had all started clinical trials by this time.

Trials under trial?

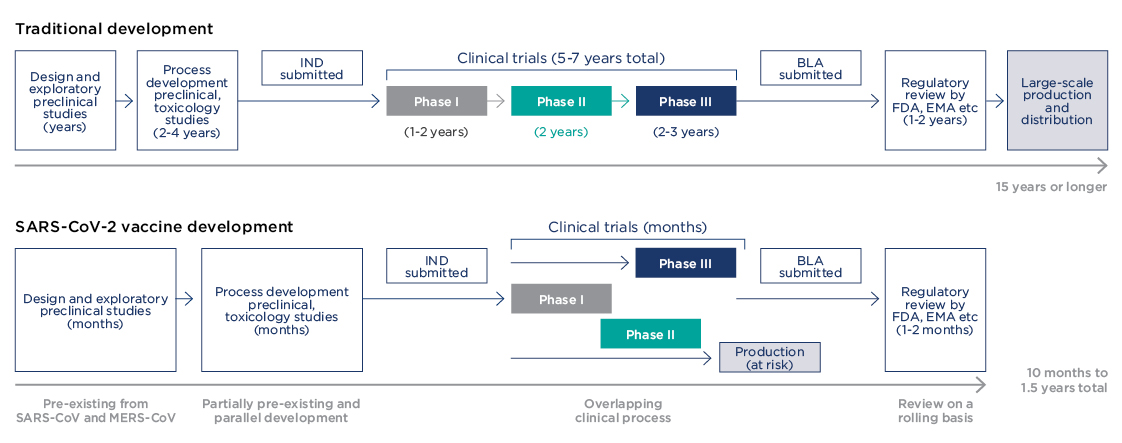

An important lesson from the COVID-19 vaccine development concerns the traditional pathway of clinical trials, which normally take 10 years or more before a drug can reach patients. In a recent article for The Conversation, Mark Toshner, Director of Translational Biomedical Research at the University of Cambridge, explained what this actually meant.

“I submit grants, have them rejected, resubmit them, wait for review, resubmit them somewhere else, sometimes in a loop of doom. When I am lucky enough to get trials funded, I then spend months on submitting to ethics boards. I wait for regulators, deal with personnel changes at the drugs company and a ‘change of focus’ away from my trials and, eventually, if I am very lucky, I spend time setting up trials: finding sites, training sites, panicking because recruitment is poor, finding more sites. I then usually have more regulatory issues and, finally, if my big pot of luck is not used up, I might have a viable therapy – or not. At this point, it might get delayed because of questions over profitability or any number of other obstacles,” he wrote.

So, whenever someone says 10 years consider … “It’s not 10 years because that is safe, it’s 10 hard years of battling indifference, commercial imperatives, luck and red tape. It represents barriers in the process that we have now proved are ‘easy’ to overcome. You just need unlimited cash, some clever and highly motivated people, all the world’s trial infrastructure, an almost unlimited pool of altruistic, wonderful trial volunteers and some sensible regulators,” Dr Toshner said.

So, what were the COVID-19 vaccine trials like? Unprecedented may be a good word, streamlined another.

“Trials were designed such that clinical phases are overlapping, and trial starts are staggered with initial phase I/II trials followed by rapid progression to phase III trials after interim analysis of the phase I/II data,” said Florian Krammer, an immunologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, in a recent review in the journal Nature.

Despite being streamlined, these clinical trials were also safe.

“All trials have been through the correct phases or process of any normal drug or vaccine. Hundreds of thousands of the very best of us volunteered and had an experimental vaccine. The world watched so closely that when a single person fell ill, we were all debating it,” Dr Toshner explained.

A key factor that played in favour of the COVID-19 vaccine was the availability of willing patients. For most drugs, recruiting enough patients for clinical trials is challenging. In the case of vaccines, for example, sometimes it takes years to recruit enough patients for a phase III clinical trial, the last milestone before going public. But not so with the COVID-19 vaccine.

“Because there were millions of people with COVID-19, they were able to recruit 40,000 people for each trial incredibly quickly, and because there was so much virus around, they got infected very quickly,” Dr Swan said.

Normally, for vaccine trials focused on a viral agent, scientists need to wait for patients to randomly become infected by the virus so that they can then test the vaccine.

“That’s simply a waiting game. We didn’t have to wait. People, unfortunately and tragically, were there and they got infected incredibly quickly and you got a result very quickly,” Dr Swan said.

Unprecedented approvals

Unprecedented approvals

The last step in the development of vaccines is regulatory approval for public use. This usually takes 1-2 years and only then can vaccines start global production. COVID-19 vaccines were approved within 1-2 months.

An important factor of their approval was that they had been tested in millions of people with no significant safety concern.

“At least in the Australian context, tens of millions had already had (COVID-19 vaccines) in the real world with no new safety signals emerging,” Dr Swan explains. “So, in terms of safety and effectiveness, thanks to the Israeli data and the British data, we are confident that they work in the real world and that they are not dangerous, at least in the short to medium-term.”

The only aspect of the COVID-19 vaccines that remains to be seen is the long-term safety as there just hasn’t been enough time elapsed.

“However, there is a very good track record in vaccines of not having problems in the long-term. So, this whole thing about a rush is a mirage,” Dr Swan said.

Perhaps a more worrisome question is how fast, efficiently and fair is the distribution of COVID-19 vaccines. So far, only one country, Israel, has vaccinated more than 50% of their population, while most countries have significantly lower vaccination levels.

As of 9 April 2021, the Australian Department of Health reported that 1,138,866 doses of COVID-19 vaccines had been given – or about 4.5% of the total population. At the time of writing this article, the Australian government had backed down from their vaccination targets due to multiple issues with distribution and administration of vaccines, and with the growing issues surrounding the safety of the AstraZeneca vaccine, which is now not recommended for those under the age of 50.

Another problem is equity. Rich countries are being accused of hoarding vaccines, while poor countries are struggling to get enough doses to vaccinate their frontline health workers.

Only time will tell how Australia and other countries will move forward with vaccination efforts, but clearly more work is needed to address all the issues at hand.