You may not have heard about arthrofibrosis but would be familiar with frozen shoulder (adhesive capsulitis), stiff knee, frozen elbow or stiff hip. These conditions are arthrofibrosis in different joints.

Despite a similar name, the pathology of arthrofibrosis, literally meaning fibrosis of a joint, is distinct from arthritis, although arthritic joints can have a degree of fibrosis that manifests as stiffness. Arthrofibrosis is a common and painful fibrotic joint disease that seriously reduces the quality of life for people of all ages and can cause permanent disability if not treated early and appropriately. Knee arthrofibrosis is particularly disabling, causing difficulty performing normal activities (e.g. standing, walking, driving and getting in and out of chairs).

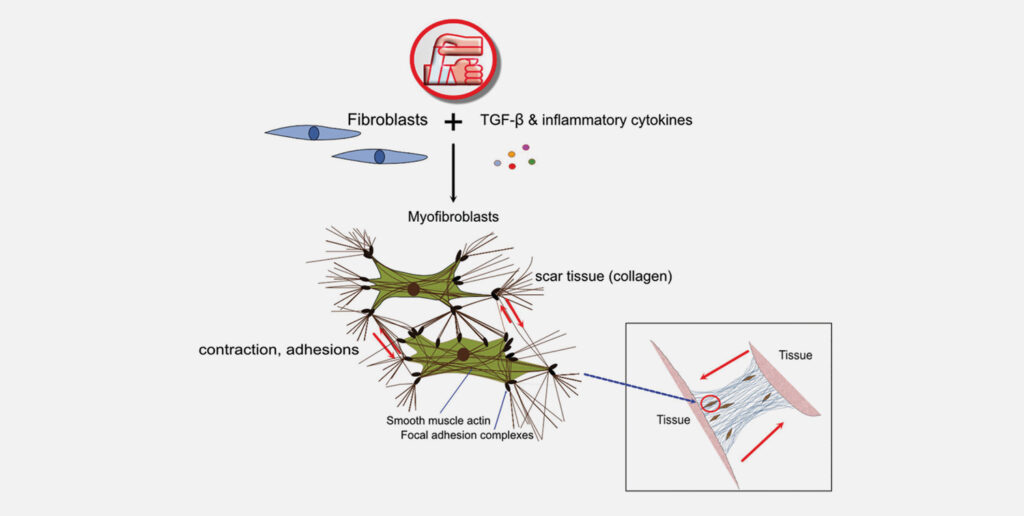

Fibrosis is a pathological state of over-healing characterised by ongoing scar tissue production, adhesions and contractions. It lies at the opposite end of the healing spectrum to diabetic ulcers (failure to heal). In joints, fibrosis can progressively invade fat pads, pouches, synovium, nerves and tendons.

Fibrosis can occur in any soft tissue, with organ fibrosis responsible for about 45% of deaths across the industrialised world, manifesting as congestive heart failure, cirrhosis, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and more.

Why does fibrosis occur?

The drivers are tissue damage, hypoxia and inflammation arising from injury, surgery or infection. With many genes involved in healing, genetics influences the risk of subsequently developing fibrosis. Autoimmune diseases and metabolic disorders sometimes contribute.

The drivers cause fibroblasts (and certain other cells) to transform into myofibroblasts, the scar makers. Myofibroblasts disappear in normal healing, but with chronic inflammation become senescent and immortal. Some risk red flags include early-onset osteoarthritis and a history of surgery in the affected joint.

About 8-10% of the population will develop shoulder arthrofibrosis, rising to 80-90% in diabetics. Following knee surgery or injury, approximately 10% will develop knee arthrofibrosis, although estimates vary. While shoulder arthrofibrosis often resolves after about a year, after 12 months knee arthrofibrosis rarely does.

Knee arthrofibrosis is particularly common after major surgery like TKRs or ACL reconstructions meaning that even young, active sporting people are at risk. Being healthy and fit, they are commonly advised to “push through the pain” and “work harder” in rehabilitation. Unfortunately, this highly motivated group will often take this advice and press on, worsening the damage and reinforcing the inflammatory cascade and subsequent fibrosis.

Paying careful attention to pain levels can create a window of opportunity in the first six to 12 months post insult to reverse arthrofibrosis. Research into organ fibrosis supports this.

For example, curing a liver infection early can reverse liver fibrosis. However, after the fibrotic processes are successfully halted, mature scar tissue can remain and limit range of motion (ROM) for years. This is residual fibrosis, differentiated from active arthrofibrosis by lacking pain and inflammation. However in a joint with active arthrofibrosis swelling, redness and heat is often minimal and easily overlooked.

Investigations include tests for autoimmune and metabolic conditions and synovial fluid to rule out chronic, low-grade infection. CT and/or MRI can rule out other conditions that may cause pain and loss of ROM. Unfortunately, MRI doesn’t readily provide an arthrofibrosis diagnosis, which is based on symptoms.

Highly modified and tailored rehab is essential for arthrofibrosis. Aggressive exercise (intensity and duration) of the affected limb is usually counterproductive and forced compliance of a joint while it’s trying to heal creates more pain, inflammation and fibrosis.

Special attention should be given to the Hoffa’s fat pad (infrapatellar fat pad), an essential immune organ. The Hoffa’s is frequently swollen in arthrofibrosis, becoming impinged and further inflamed during standing and walking. Offloading the joint using crutches for four to six weeks post-op/injury allows this to settle while regular passive stretching in the pain-free zone can increase ROM and reduce adhesions. Experienced physiotherapists recommend exercising other body parts rather than the affected limb until well down the recovery path, and then increasing use of the joint incrementally over time, as tolerated.

Aspirin (not other NSAIDs) and omega 3 fatty acids promote natural resolving pathways, and metformin and Losartan are used off label for their anti-fibrotic effects. Surgery is a last resort. Even with excellent care, the outcome is unpredictable and symptoms may worsen. Manipulation under anaesthesia – forcing ROM – risks severe complications and the immediately improved ROM is often rapidly lost.

People with arthrofibrosis need understanding and compassion. They are dealing with an invisible, painful disease that threatens their livelihoods and independence. More information is available at https://www.arthrofibrosis.info

Key messages

- Arthrofibrosis is a common but often missed condition

- Diagnosis is based on symptoms

- Correct treatment improves quality of life.

Author competing interests- nil