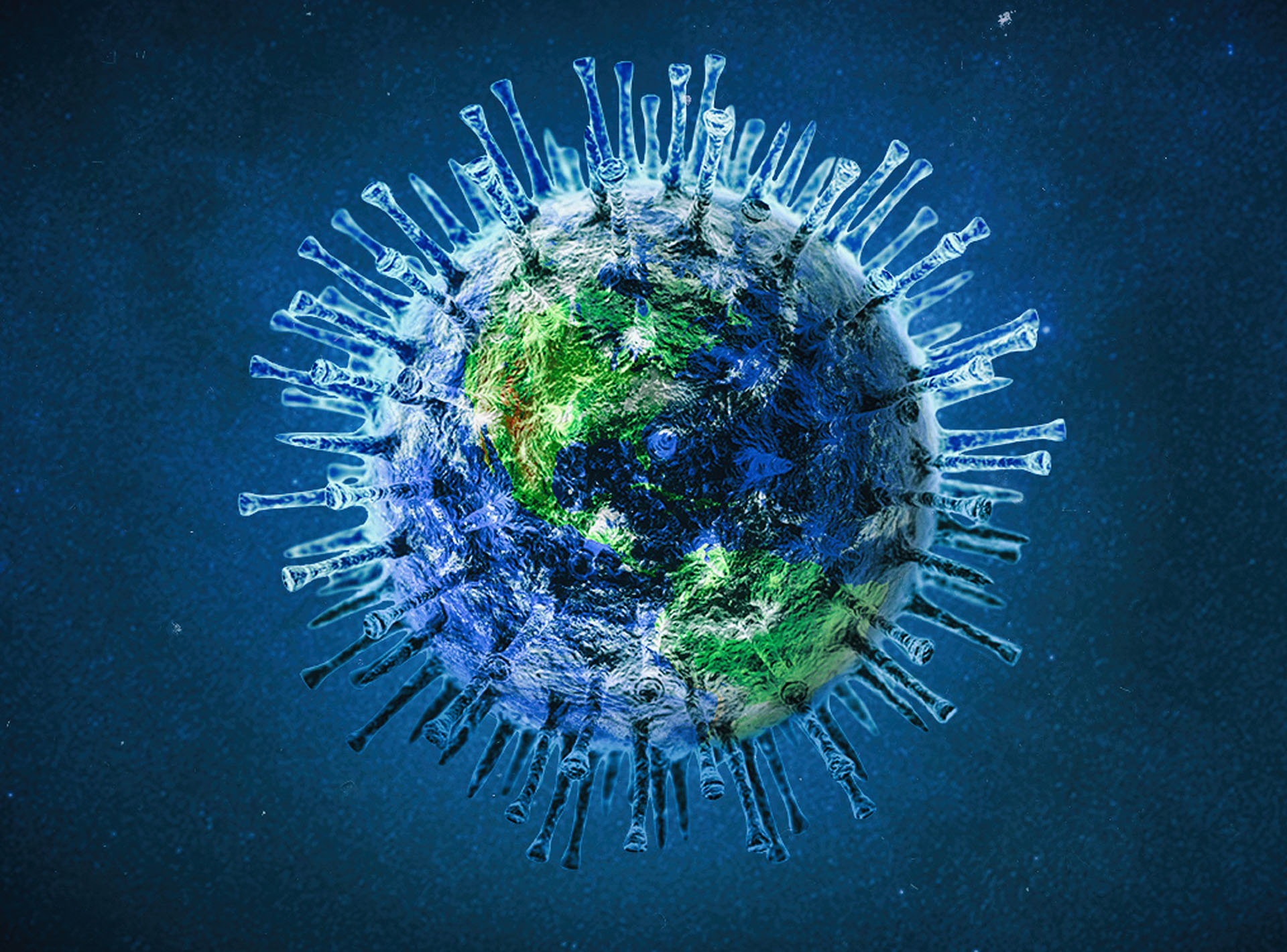

More than half of human diseases have been exacerbated by climate change according to a new study from the University of Hawaii.

More than half of human diseases have been exacerbated by climate change according to a new study from the University of Hawaii.

The comprehensive meta-analysis by UH found that the threat posed by 58% of diseases caused by pathogens, such as dengue, hepatitis, pneumonia, malaria, Zika and others, had been heightened by climatic hazards linked to global warming.

The startling results, published August 8th in Nature Climate Change, revealed that warming temperatures, precipitation, floods, drought, storm, land cover change, ocean climate change, fires, heatwaves, and sea level changes were all found to influence diseases triggered by viruses, bacteria, animals, fungi, protozoans, plants and chromists.

Camilo Mora, professor of geography at UH’s College of Social Sciences, director of the Carbon Neutrality Challenge and lead author of the study, explained that 218 out of 375 known human pathogenic diseases have been affected at some point by at least one climatic hazard, via 1,006 unique pathways.

“Given the extensive and pervasive consequences of the COVID pandemic, it was truly scary to discover the massive health vulnerability resulting as a consequence of greenhouse gas emissions,” Professor Mora said.

“This is just mind-blowing… we are messing around with fire when it comes down to climate change, because basically climate change… is like a key to a Pandora’s box when it comes down to diseases.

“There are just too many diseases and pathways of transmission for us to think that we can truly adapt to climate change – it highlights the urgent need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions globally.”

The researchers carried out a systemic search of more than 70,000 scientific papers for empirical examples about the impacts of 10 climatic hazards (warming, drought, heatwaves, wildfires, extreme precipitation, floods, storms, sea level rise, ocean biogeochemical change, and land cover change) on each pathogenic disease.

Crucially, their findings revealed that as pathogens are primarily transmitted by vectors (such as mosquitoes, ticks, fleas, birds, and several mammals), factors such as higher temperatures and precipitation changes often led to an associated expansion of these vectors’ range or territory.

Or in other words, climate change has forced pathogens and their vectors into closer contact with people. For example, the 2021 mouse plague in rural NSW was caused by a ‘perfect storm’ of climatic conditions – a long drought that killed off predators, followed by a mild, moist summer which encouraged them to breed.

Horrific scenes emerged of houses overrun with vermin and numerous reports of zoonotic infections were recorded.

Similarly, the converse is also true: climate change is bringing people closer to pathogens, with the forced displacement and migration of people due to weather events and warming encroaching on formerly wild habitats.

Climatic hazards have also enhanced specific aspects of pathogens, including improved climate suitability for reproduction, acceleration of the life cycle, increasing seasons/length of likely exposure, enhancing pathogen vector interactions (by shortening incubations) and increased virulence.

For example, rising sea levels have been implicated in increasing cases of leptospirosis, cryptosporidiosis, lassa fever, giardiasis, gastroenteritis, legionnaires’ diseases, cholera, salmonellosis, shigellosis, pneumonia, typhoid, and hepatitis – just to name a few.

Climatic hazards have also diminished human capacity to cope with pathogens by altering body condition; adding stress from exposure to hazardous conditions; forcing people into unsafe conditions; and damaging infrastructure, reducing access to medical care.

“We knew that climate change can affect human pathogenic diseases,” PhD student and co-author Kira Webster said.

“Yet, as our database grew, we became both fascinated and distressed by the overwhelming number of available case studies that already show how vulnerable we are becoming to our ongoing growing emissions of greenhouse gases.”