Anaesthetists have always played a leadership role in patient safety. Stanford’s David Gaba and University of South Australia’s William Runciman, both giants in their field of anaesthesia and patient safety, recognised the organisational similarities between aviation and anaesthesia and adapted aviation safety initiatives. In particular, the introduction of simulation, crew (crisis) resource management and the use of cognitive aids have been embedded in specialist training programs.

What is a cognitive aid?

In its simplest form, a cognitive aid (CA) can be defined as any external representation supporting the cognitive processes demanded by a task.

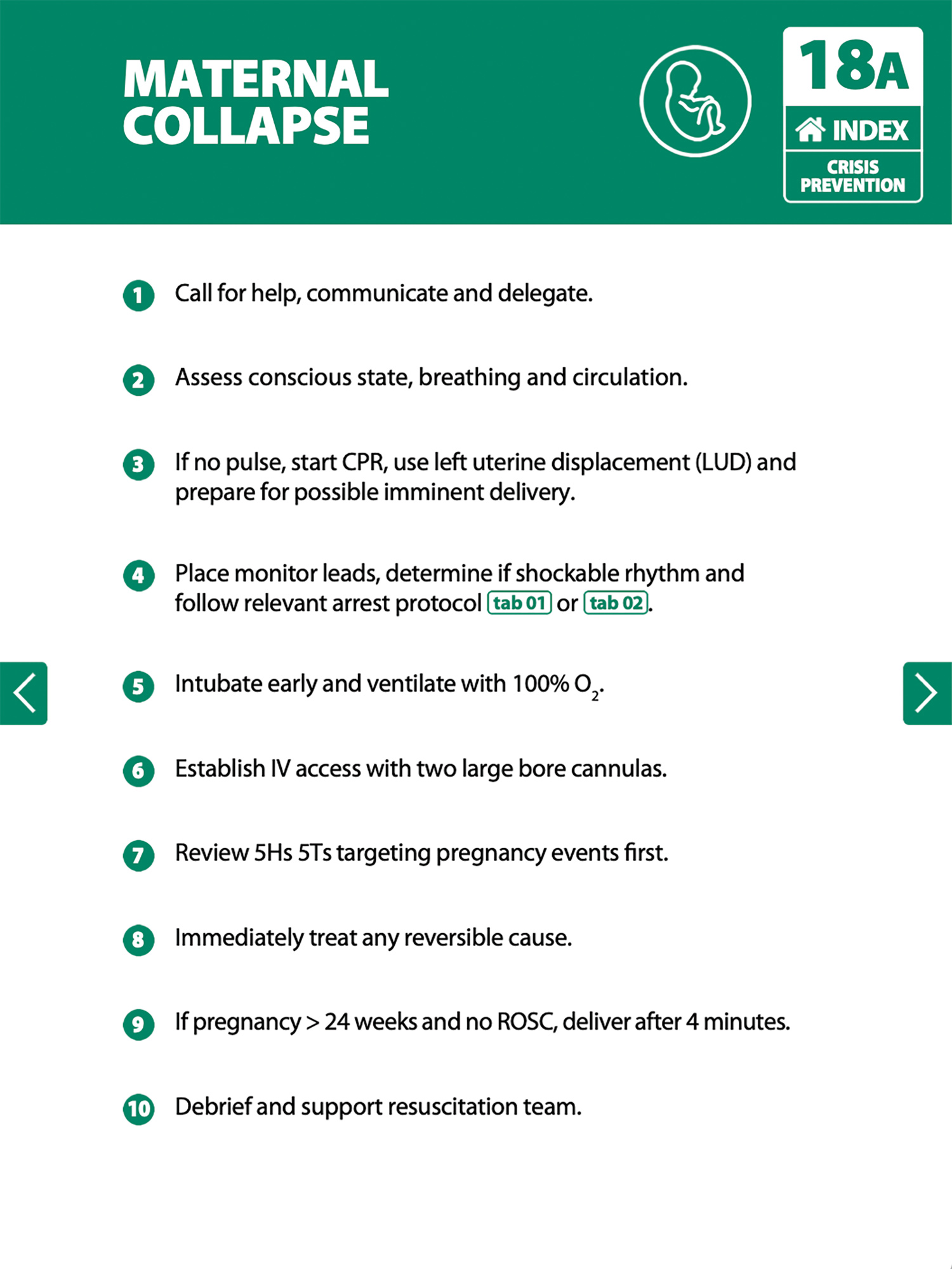

In the peri-operative environment they include checklists, ‘track and trigger’ charts as well as crisis manuals. CAs have been shown to improve mortality and morbidity rates in healthcare settings and are considered an integral component of patient safety. Simulation studies demonstrate better communication, a reduction in adverse events, improved implementation of evidence-based guidelines and less errors of omission.

Written or electronic checklists, guidelines and protocols are formatted specifically using minimalist design principles to assist the user in completing complex and ‘tightly coupled’ tasks (requiring high degrees of synchronisation amongst team members).

Integrated collections of single-page CAs for operating room emergencies were first implemented in 2003 by Gaba in US Veterans Affairs hospitals. This was followed by commercially available, colour-coded, aviation-type manuals such as The Anaesthetic Crisis Manual and freely available downloadable manuals or checklists such as the Stanford Emergency Manual and Harvard’s Operating Room Emergency Checklists.

Despite widespread use and the specific design parameters of aviation’s Quick Reference Handbook (QRH) checklists, on which many were based, crisis management cognitive aids in anaesthesia are not standardised. The most successful present a two-page layout with directives on one side and supportive information opposite.

The concept is relatively simple. Ideally, the operating room team responding to a crisis will be directed by a team leader. Depending on the context, this may be the anaesthetist, a member of the MET team or critical care consultant. The role of a ‘reader’ is assigned to a staff member who will use the appropriate manual protocol to follow team actions, confirming task completion or prompting when necessary if

The concept is relatively simple. Ideally, the operating room team responding to a crisis will be directed by a team leader. Depending on the context, this may be the anaesthetist, a member of the MET team or critical care consultant. The role of a ‘reader’ is assigned to a staff member who will use the appropriate manual protocol to follow team actions, confirming task completion or prompting when necessary if

steps are missed.

Widespread implementation of crisis manual type CAs has not been as successful as the WHO’s Surgical Safety Checklist. This can partly be explained by reluctance of practitioners to accept that cognitively ‘offloading’ during crisis management using CAs is actually good medical practice – not indicative of weakness or incompetence.

Studies have repeatedly shown even the most senior clinicians can miss important steps in treatment guidelines, especially with high pressure, time sensitive and rare or infrequent events. CA support can alleviate anxiety associated with the ‘am I missing something?’ phenomenon and provide a shared mental model for all team members.

However, with emergency manual incorporation into curriculums and simulation training, as well as College and Society endorsement, newer generations of anaesthetists appear more accepting. With rapidly expanding medical knowledge and the medicolegal implications of adhering to best practice guidelines, it is likely routine use of manuals is not far away.

Despite these relatively recent developments in the field of anaesthetic crisis management, it is with a somewhat heavy heart that we anaesthetists must acknowledge the concept of resuscitation protocols and drills was first documented almost a century ago by a surgeon, W. Wayne Babcock, famed for the well-known instrument.

In his 1924 article, Resuscitation during anesthesia, Babcock asked:

“Have you a plan of action so developed that the right thing is always done in the emergency and time is not frittered away with useless or non-essential details?”

The aviation adage that regulations are written in blood reflects the loss of life underpinning checklists and protocols. It equally applies to healthcare. We should heed Dr Babcock’s advice and utilise crisis management cognitive aids to maximise team performance and provide the best emergency care.

Key messages

- Cognitive aids are an integral safety component of High Reliability Organisations (HROs) such as aviation and nuclear energy

- During complex life-threatening crises, individuals rely on cognitive tasking far beyond the information processing capacity of the human brain

- Evidence suggests the surgical safety checklist and crisis management cognitive aids lead to better patient outcomes.

– References available on request

Author competing interests – the author is a director of Leeuwin Press