“Low back pain and neck pain are the two largest causes of musculoskeletal disability” – Global Health Metrics, Lancet. 390, 2017

Pain in, or coming from, the spine is common. In a relatively small number of cases, spine surgery can help alleviate the pain. However, it is an inherently painful option and there is a clear proportion of patients who never really ‘climb out of the hole’ of pain and suffering post-surgery, nor feel an overall benefit from surgery.

Pain is one of the most complex human experiences and varies enormously between individuals. Many factors involved in the degree of the suffering experienced are outside of the surgeon’s control (though always considered and managed where possible). Some elements, however, are, to some degree at least, within the surgeon’s control.

Put simply, the basic problem with spine surgery is that the structures we need to access are deep and encompassed by muscle that contracts with almost every movement we make. We need to dissect this muscle from its attachments, stretching it open to gain visibility underneath. This defunctions and often denervates fibres producing mechanical disadvantage for the remaining muscle. All of this is painful.

We often need to dissect more muscle and sometimes bone than we would like to as we need to recognise various anatomical elements in order to form a three-dimensional picture of the pathology in order to operate safely. This is particularly so when inserting implants into the spine such as pedicle screws.

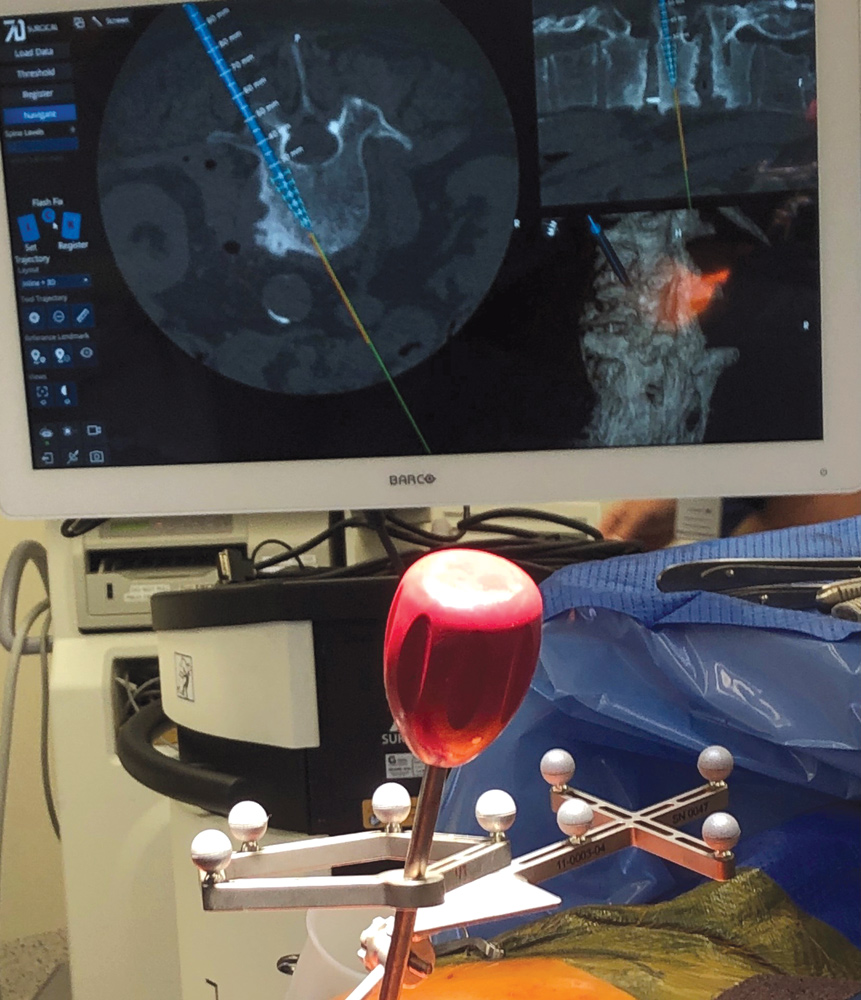

In traditional methods, we often need to ‘strip’ the spine fairly aggressively in order to place screws safely to get a sufficient view. Minimally invasive spine surgery methods attempt to reduce the degree of dissection and muscle trauma and, therefore, reduce the pain associated with the procedure. This reduction in pain has been well proven in the literature. One method to achieve pain reduction is using computer navigation and percutaneous screw insertion. This is, in essence, an augmented three-dimensional visualisation technology in that we place screws ‘virtually’ on a trajectory displayed on a computer screen, whilst simultaneously inserting the screw in real time into the patient.

In traditional methods, we often need to ‘strip’ the spine fairly aggressively in order to place screws safely to get a sufficient view. Minimally invasive spine surgery methods attempt to reduce the degree of dissection and muscle trauma and, therefore, reduce the pain associated with the procedure. This reduction in pain has been well proven in the literature. One method to achieve pain reduction is using computer navigation and percutaneous screw insertion. This is, in essence, an augmented three-dimensional visualisation technology in that we place screws ‘virtually’ on a trajectory displayed on a computer screen, whilst simultaneously inserting the screw in real time into the patient.

The system is loaded with a pre-op CT scan, we fix a 3D array to the patient, usually with a clamp on the tip of a spinous process or with a narrow pin into the top of the iliac crest, and we then ‘demonstrate’ a small portion of bony anatomy to the navigation device by tracing it out and the computer does the rest.

Navigation has been shown to improve the overall accuracy of pedicle screw placement but relying solely on navigation can increase the risk of implant misplacement as a result of technical errors.

Overall, minimally invasive spine surgery has been well shown to reduce pain, blood loss, hospital length of stay and speed of recovery. As with all complex surgery, appropriate patient selection greatly influences outcomes.

Key messages

- Spinal pain is common, multifactorial and not always relieved by appropriate surgery

- New computer-assisted surgery can improve outcomes in suitable patients

- Minimally invasive surgery can reduce pain, blood loss and hospital stay and speed up recovery.

Author competing interests – nil