Bunbury psychiatrist Dr Steve Blefari won’t let distance hold him back from helping solve the rural disadvantage in mental health care.

Bunbury psychiatrist Dr Steve Blefari won’t let distance hold him back from helping solve the rural disadvantage in mental health care.

Jan Hallam reports

Long before COVID, health workforce numbers and training in Western Australia have been worrisome issues that have kept health services searching for sustainable answers.

While metropolitan Perth may have its workforce challenges, they pale against those at the frontline and in the engine rooms of health services in the seven regions of our vast state.

Here, the population may be relatively few, but the burden of disease is great, with mental health one of the heavier items, and accessibility to services has undeniably played a significant role in that conundrum.

The WA Country Health Service has warmly embraced the ‘grow your own’ strategy, which, in 2022 can bank on doctors being produced by three medical schools and reap the benefits of the success of the Rural Clinical School WA (RCSWA) and WAGPET (both 20 years in the making).

There is mounting evidence that the longed-for ‘sticking’ of these locally grown medical students and young doctors after early exposure to regional practice is eventuating.

However, there remains barriers to achieving a stable multi-layered workforce, and longer-term career development and prospects can be counted among them.

Here there are some positive developments, with WACHS establishing a number of rural specialist pathways, and the newly minted psychiatry iteration is a good example of what happens when overwhelming need meets vision, leadership and commitment.

Medical Forum spoke to Bunbury psychiatrist Dr Steve Blefari, left, who along with colleague Professor Mat Coleman in Albany, has been working with WACHS and the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) to develop an integrated specialist psychiatry program that would allow its trainees to fulfil their AMC accreditation and fellowship requirements all within country WA.

Building blocks

“We have been working on this for a few years. With our work with the RCSWA and WACHS we have been running projects through the regional training hubs. And with Mat’s work as chair of the college’s Section of Rural Psychiatry we have found a synergy,” Dr Blefari said.

Between WACHS’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy 2019-2014 and the college’s Rural Psychiatry Roadmap 2021-2023, the will appears to have found a way.

A 2015 Department of Health workforce projection of a ‘high’ psychiatry shortfall in 2021 has already played out, a ‘critical’ shortfall is forecast for 2025, while current and predicted demand for psychiatric services is far beyond capacity if action is not taken.

Dr Blefari said that Australia had 13.5 psychiatrists per 100,000 people, and it was the same rate in metropolitan Perth. In the rankings, that puts Australia ninth, behind No. 1 Norway (48 per 100,00 and the OECD average of 15.3)

“In rural and regional WA, there are 4.3 psychiatrists per 100,000 people, which is a little bit more than Mongolia (4) but less than Bahrain (5.5),” he said.

“Looking at the WA training figures back in 2014, we took in 18 new trainees. Over the next six years we took annually 12, 21, 17, 19, 19 and 17 trainees. So, between 2014 to 2020, we have had no workforce growth at all,” Dr Blefari said.

“We have a very metro-centric medical education system, and that’s not just psychiatry. However, there has been an underinvestment in rural psychiatry and training, which means we have produced fewer trainees and that contributes even more inequity.

“This training bottleneck has exacerbated the cycle of disadvantage. And yet through the 15 sites of the RCS, rural WA sees a lot of medical students, and specialist training hubs are beginning to develop where young doctors can do their internship and also some of junior medical years.

“If you want to be a psychiatrist, you have to go back to Perth to do the bulk of your training.”

This missing link in the training process is also a missed opportunity to train and retain psychiatrists in the regions.

The specialist training cycle can be one of ever decreasing circles that starts with the number of trainee positions, which is dictated by mandatory terms and the number of supervisors … and of course funding.

In their hands

In their hands

“With the support of the WACHS Chief Executive and Board, WACHS is proposing to take control and do all of that, provide the funding, provide the supervisors and take over the training, essentially.”

Dr Blefari said.

“The long game is building mental health capacity in the regions. We have a lot of medical students on placement, we’ve got PGY1 and PGY2 placements doing mental health terms and we’re also now starting to do some GP registrar placements as both GP colleges (RACGP and ACRRM) have curricula for advanced skills in mental health. And we also have international medical graduates coming through our services interested in training in mental health.

“Interest in psychiatry is not the problem. In 2022, the WA metropolitan program had 70 applicants for 22 positions. So, there were nearly 50 people wanting to do psychiatry training who were turned away. This is not the case in other states.

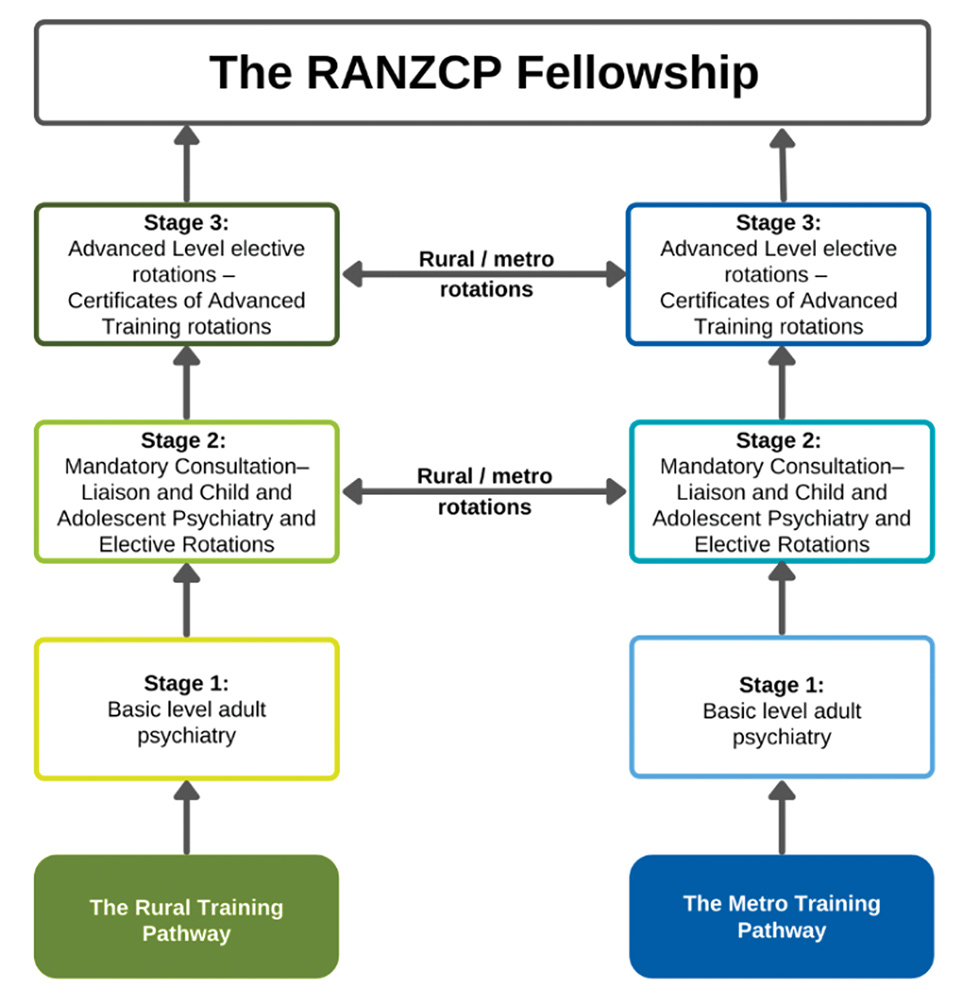

“We have lobbied the WA training committee to establish our own Rural Training Subcommittee and the original thought was to have a rural pathway within the metro training program. But now we will have a metro training program and a rural training program, though it will be nominated as a rural zone, which we are hopeful to have up and running in 2023.

“This will allow us to recruit directly to WACHS for first year registrars, and we’ll be able to keep them in placements all the way through their training, if they want to.

“There’ll be some opportunities for metro placements for subspecialty types if that’s what they’re interested in. For the rural zone, we’re really promoting rural generalist psychiatry and we’ll be able to provide the whole five-year program across many of our sites.”

Commonwealth funding through RANZCP for four (out of 30) national specialist training positions (STPs) has been secured ($125,000 per trainee and $90,000 for supervisors) and that is now active, and Dr Blefari is hopeful that funding will remain for supervisors until 2026. The application nominates sites in the six of the seven regions. It is hoped that the Goldfields will follow once its capacity develops.

Plan expands

WACHS already provides placements in the South West, Great Southern and the Kimberley and those three sites will develop into the main training hubs. Additionally, there will be work to accredit posts in Pilbara, Midwest and Wheatbelt regions. When the rural zone starts, there will be experiences throughout the state.

Given the unique needs within the regions, Dr Blefari said the diversity of experience for trainees will be vast.

“Within a five-year program, a trainee might spend the majority of their time in a regional centre like Bunbury but have the opportunity to go to Karratha or Port Hedland or Kununurra. If we give trainees these extraordinary experiences, they might then want to go back there to work.

“Within a five-year program, a trainee might spend the majority of their time in a regional centre like Bunbury but have the opportunity to go to Karratha or Port Hedland or Kununurra. If we give trainees these extraordinary experiences, they might then want to go back there to work.

“We work with experienced multidisciplinary teams and our supervisors are committed to producing excellent practitioners. There’s also lots of research going on in a range of areas including Aboriginal mental health and plenty of work outside of the clinic and hospital setting. WACHS has Aboriginal Mental Health staff embedded in the multidisciplinary teams and this learning experience for psychiatry trainees is invaluable.

“We also provide accommodation, and we don’t have any on-call, but we’re also honest about the downsides – the training cohort might be a little smaller and a lot of the education will be via video conference. You can’t pop out to Leederville for a coffee, and you’ll probably run into your supervisor at the pub.

“Often you will have to travel for exams, but due to COVID we’ve already worked with the college to provide some of those exams locally.

“In the hubs, we’ve got inpatient, community, child and adolescent, older age and consultation experiences available and lots of supervision and study support.”

For now, the rural zone is going through its accreditation with the college, but Dr Blefari is thinking long term.

Five-year plan

“We have come up with a five-year growth plan that I think we can realistically achieve across WACHS. If the rural zone is approved and we can recruit trainees directly, instead of metro giving us people with a rural preference, and then only for a short time, we can start recruiting, conservatively in the first year.

“When we recruit two to the South West and two to the Great Southern, on top of the trainees we’ve already got, which is about seven, then increase it incrementally, to have the first years come through those hubs initially then into Kimberley and Mid West and Kalgoorlie by 2027, we can graduate 34 psychiatrists over 10 years, which is really, really exciting.

“We know there are barriers and we are tackling them.

“We have to be innovative and forge on. We are committed to welcoming new trainees from 2023 onwards.”