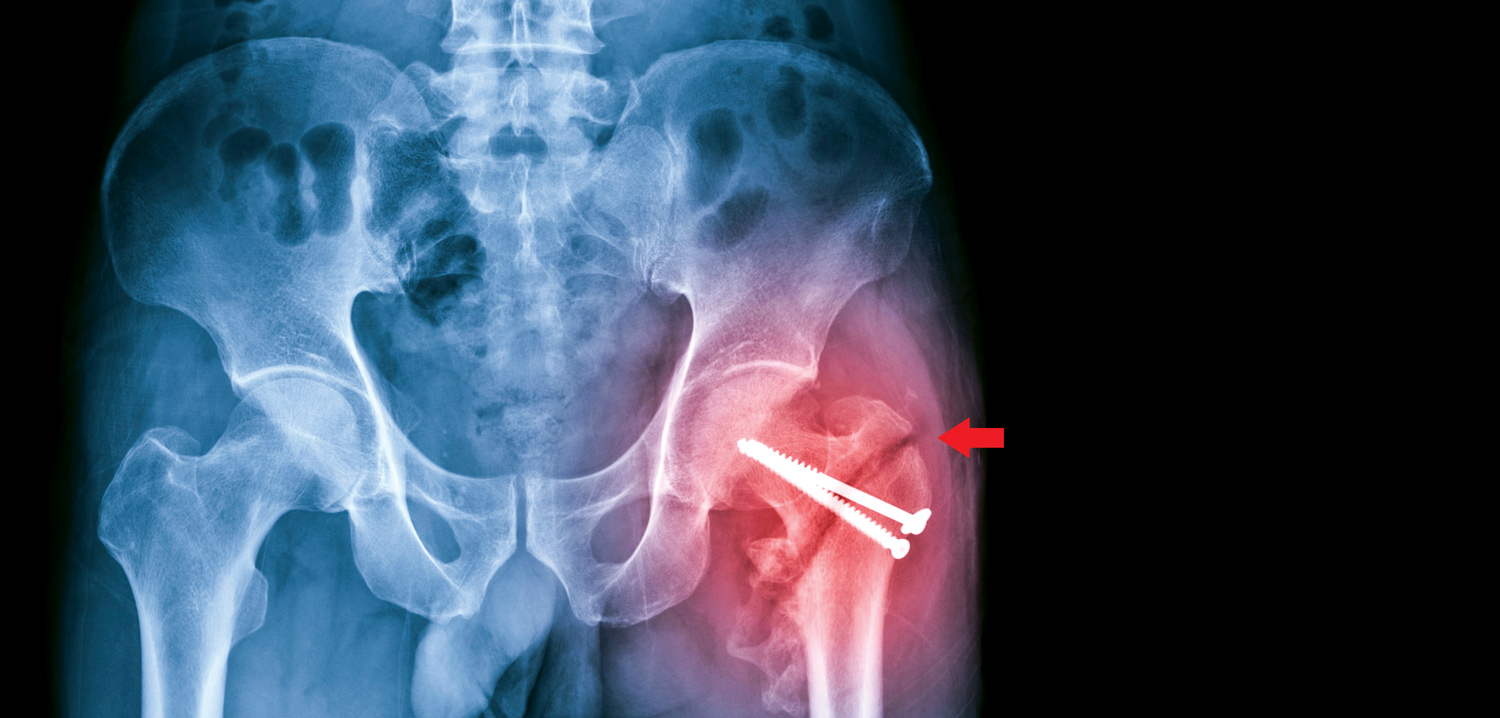

Every year, more than 19,000 Australians – many of them elderly – fracture their hip. Now revised guidelines are aimed at ensuring they get more timely treatment.

Every year, more than 19,000 Australians – many of them elderly – fracture their hip. Now revised guidelines are aimed at ensuring they get more timely treatment.

By Cathy O’Leary

WA geriatrician Dr Hannah Seymour knows only too well that time can be the enemy when treating people who break their hip, particularly when facing geographical barriers.

Based at Fiona Stanley Hospital, her experience of working closely with older patients who have had a hip fracture means Dr Seymour understands that prompt surgery reduces pain, speeds recovery and reduces time spent in hospital.

Yet as hip fracture surgery can only be performed at larger hospitals with suitable facilities, some people in regional and remote areas have to be transferred long distances. In 2022, 14% of hip fracture patients in Australia were transferred from another hospital for their surgery.

However, updated guides for the care of hip fractures are now calling for hospitals to move more quickly to get patients into theatre – and up walking after their surgery.

The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) launched a revised national clinical care standard for hip fracture in September at the binational Hip Fest 2023 conference, hosted by the Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry.

Cut the wait

The standard was first launched in September 2016 to guide consumers, clinicians and health services on delivering appropriate care to people with a hip fracture. The revised standard reduces the recommended maximum time to surgery, along with other improvements for better care.

The commission said many people with a hip fracture were waiting longer than was optimal for surgery, despite some hospitals making big improvements in the past few years.

Australia’s ageing population made improvements to hip fracture care even more important, as most fractures occur in people aged over 65 who are more vulnerable to complications.

Hip fracture significantly increases an older person’s risk of death, with one in four people dying within 12 months. Of those who survive, many lose their ability to live independently or return to their former lifestyle.

The updated standard for hospitals has reduced the maximum time to surgery from 48 hours to 36 hours, in line with international guidelines. For the first time, this explicitly includes patients who need to be transferred to a hospital that can perform the surgery.

Network needed

The revised standard calls on healthcare services to build effective systems and networks with other facilities to ensure coordinated transfer and help all patients receive timely surgery.

For Dr Seymour, this change in the standard will be a key driver to improve time to surgery for all patients.

“Nationally, we haven’t reduced our average time to surgery and are failing patients. It is disappointing and needs to change because frail, older people are lying in hospitals in pain for longer than they need to be.

“We know that it is possible to reduce the time to surgery if you have the right systems in place,” she said.

“We’ve shown in WA that it often takes just as long for a patient being transferred for surgery from a hospital 45 minutes away by car, as it does for someone flown in from hundreds of kilometres away. It doesn’t matter where you transfer from, all patients are waiting, even if they are just down the road.”

Dr Seymour has long advocated for older people needing a transfer to a larger hospital for hip surgery. WA Health has streamlined interhospital transfer, so there are now clear arrangements for hospitals in smaller WA towns to know where they need to transfer the patient.

The ACSQHC’s acting chief medical officer, emergency physician Associate Professor Carolyn Hullick, said there was an urgent need for health services to offer better care for people with a hip fracture, using the framework in the updated standard.

“Anyone who has seen someone live through a hip fracture knows it’s much more than a broken bone,” she said. “People with a hip fracture tend to be older, frail and more vulnerable, so it is critical the fracture is repaired quickly to reduce pain and get them on the road to recovery and back to independence.

“The data is sobering, as an Australian with a hip fracture is almost four times more likely to die within a year than someone of the same age who isn’t injured. This has an immense personal toll on individuals and families, in addition to the burden on our health system of around $600 million each year.”

Much has improved since the Hip Fracture Clinical Care Standard was introduced in 2016, according to ANZHFR annual reports, with 91% of hospitals performing hip fracture surgery in Australia participating to help improve their hip fracture care.

An evaluation of the standard in 2020 found that 98% of respondents reported that the standard improved care when implemented by their organisation; and 96% of respondents said the standard was relevant to their practice.

Times vary

But while some hospitals had substantially reduced their time to surgery, there was still marked variation.

In 2022, the average time to surgery ranged from 16 to 92 hours, with the longest waiting times for people being transferred for surgery. About 78% of patients had surgery within 48 hours.

Geriatrician Professor Jacqueline Close, Co-Chair of the ANZHFR and the expert advisory group for the standard, believes the updated standard will be a lever for change.

“The Hip Fracture Clinical Care Standard sets expectations for how every patient should be cared for, while allowing for treatment to be tailored to the individual,” she said.

“The adage ‘don’t let the sun set twice before hip fracture repair’ has merit.

No one wants to see their mum or dad fasting and in pain waiting for surgery; and shorter time to surgery is associated with fewer complications, better recovery

and survival.

“It is also more cost efficient to manage these patients well. Every day surgery is delayed, two days are added to the length of stay. The sooner you operate, the quicker patients can get walking and go home.”

Professor Close said the registry data showed Australia could do better in several key areas of hip fracture care. “The evidence tells us the sooner you are supported to get out of bed, the better your functional recovery. Last year, fewer than half of patients walked on the first day after hip fracture surgery.

“Also, only one third (32%) of patients leave hospital on bone protection medication for osteoporosis to prevent another fracture. We absolutely can and should do better,” she said.

For 85-year-old Esperance grandmother Jill Bower, it was a relief to know she was in good hands when she arrived by ambulance at Esperance Hospital after fracturing her hip. The ED team swung into action to transfer Jill from the coastal town to Fiona Stanley nearly 700km away, with the Royal Flying Doctor Service.

“At Esperance they gave me the nerve block in my groin for pain before they moved me, which was great,” she said. “Early the next morning they put me on the RFDS flight, and I arrived in Perth by midday. I went straight to Fiona Stanley Hospital because they’d been warned – so I got a bed straight away, I didn’t have to wait.”

The whole process meant that Jill had surgery less than 48 hours after presenting to Esperance Hospital. The next day, she began her recovery under the care of Dr Seymour.

“They got me up the day after surgery on a tall frame and I felt good. Later they changed me onto a four-wheel walker and had me walking up the hallways once a day, using the side rails to keep me moving.”

Jill completed her recovery in two smaller hospitals where she was able to build up her strength before heading home to Esperance on a regional flight.

Dr Seymour said that for a patient like Jill, Esperance was too small a place for surgery at the local hospital, but staff could deliver a nerve block and knew which hospital to call.

“The patient is put on our surgery list when they call, so are in the queue based on the time of fracture,” she said.

“Established communication channels are now in place, and much of the time we can operate in that 36-hour window because we have a system with transfer protocols and straight-to-ward arrangements.

“We have a partnership with the RFDS who know that Fiona Stanley Hospital wants to operate promptly and that the patient is already on their list, even though they aren’t physically in the hospital.”

The WA Country Health Service team also worked hard with their emergency departments to ensure staff were well-trained to deliver a nerve block prior to moving patients, ensuring effective pain relief.

Dr Seymour said it was encouraging that 90% of hip fracture patients nationally now received nerve blocks before surgery, but sometimes only in the operating theatre. She supports the increased emphasis in the revised standard on patients receiving nerve blocks before transfer to decrease pain during transportation.