Psychiatrist Dr Richard Magtengaard has a soft spot for the hearts, bodies and minds of those in the military, veterans and first responders.

Psychiatrist Dr Richard Magtengaard has a soft spot for the hearts, bodies and minds of those in the military, veterans and first responders.

By Ara Jansen

“Simply, you have to be very comfortable with angry men,” says Dr Richard Magtengaard.

Fascinated by people’s stories, this psychiatrist works primarily with defence personnel, veterans and first responders and the interesting and unique mental issues they face as a consequence of their jobs and duty.

While some of issues can be similar to those we all face – fighting with a spouse or an issue with a colleague – there are also experiences specific to them such as PTSD from combat, attending serious vehicle accidents, violent crime scenes and feeling adrift after leaving service.

Richard’s empathy and ability to relate to his patients come not only from his years of practice but also from having been in the military himself. He’s either seen or experienced much of what these people are seeking help for.

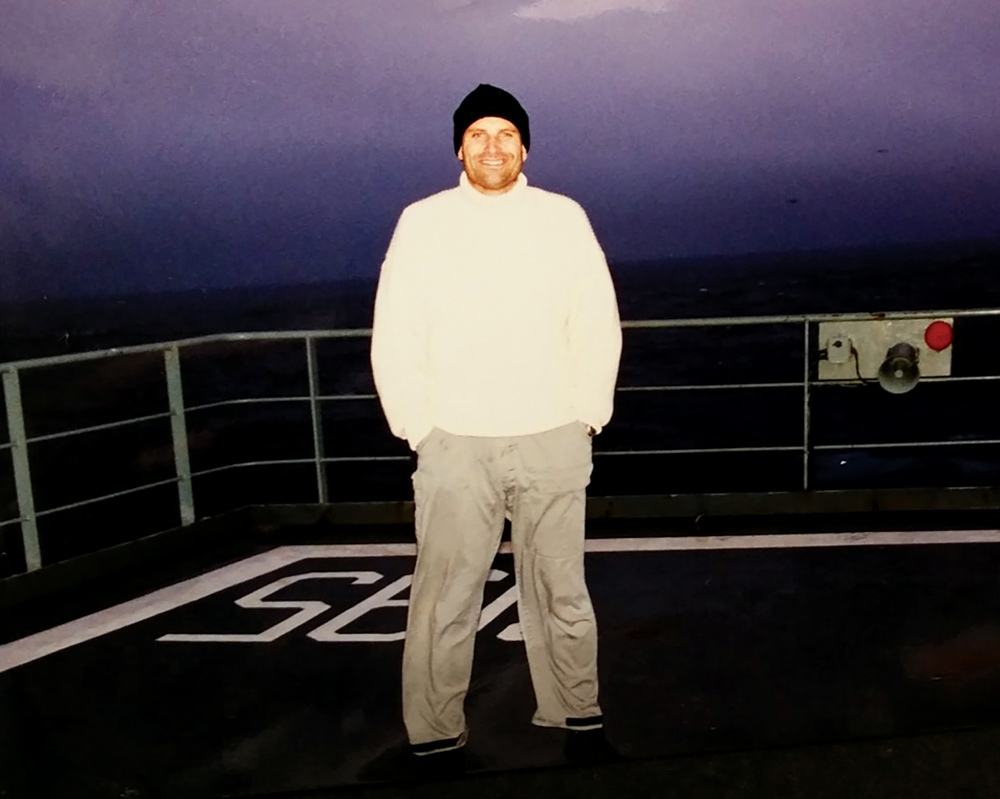

Growing up in Ceduna, South Australia, Richard joined the Royal Australian Navy and was a commissioned officer for 10 years. In his final two years he was posted to Fleet Base West on Garden Island off the coast of Rockingham. It was there he began studying medicine for the next step of his career. He went to Brisbane to continue his studies and returned in 2003 to Perth, where he bases his practice.

Richard initially worked in the public health system and went private in 2012. Now he specialises in mental health problems in veterans, defence personnel, first responders and their families. This includes post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), mood disorders, chronic pain, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and general adult psychiatry.

Uni v Navy

Uni v Navy

“I realised I didn’t want to be an academic and the idea of being at a desk didn’t thrill me,” says Richard. “I had a scholarship to do a bachelor of science at Adelaide University, which included a lot of biology courses.

“I met a number of medical students who were doing their six years and while medicine interested me, I was also interested in joining the Navy as a Warfare Officer (or similar). In retrospect I really think my medical practice benefited from the life experienced prior to studying medicine.”

Richard’s father had a construction company, which worked on the naval ships and submarines, which as a kid and young man gave him a chance to look around the decks and engine spaces.

“The idea of sailing out on them was intriguing and my naval service was rewarding in many ways. However, after 10 years I reached the point that many, if not all service personnel find themselves at. ‘Should I stay, or should I go?’

“The nature and rigours of service mean a lot of time spent away from home and that can have a detrimental effect on relationships with loved ones and time away from children that can never be retrieved.

Shared insight

“Having this shared experience with patients is highly valuable within our therapeutic relationship. Shared hardships, the nuances of service life, all of the unspoken aspects that allow me to empathise and understand, causing my patients to feel heard and understood.

“So, I made the decision to leave and my interest in medicine was reignited, and after much application I gained my medical degree. I was fortunate to have this alternative plan, but I still found transitioning out of the navy a difficult period of adjustment.

“This is recognised as a high-risk period for personnel leaving service, so this is another aspect where my personal experience makes a real difference in my patient interactions.

“I wasn’t set on becoming a psychiatrist from the outset, but it was a specialty that always interested me and kept coming back to me. Surgery is often thought of as a military type of specialty and I was interested in obstetrics and gynaecology. Unsurprisingly though, babies don’t work to a regular timetable and proved to be almost as good as the navy at keeping me away from home.

“I really enjoyed the complexity of O&G and the interplay between the arrival of the children and the parents. I also liked the multi-disciplinary team but was really fascinated by how parents would express themselves and what they wanted.”

Through his studies, training and general grounding, Richard discovered grief counselling before transitioning fully to psychiatry. That’s where he really found his calling.

It has been in the past six to seven years that he’s come to focus on defence, veterans and first responders and the distinct set of issues they deal with.

“There are a number of studies that have come out that have validated just how tough it is to do these jobs. More recently, as a consequence of COVID, we really have to be looking after the people who are looking after us – and helping them look after themselves.

“It’s a validating space to work in. Thanks to groups like Beyond Blue there has been a large leap with defence veterans seeking help. You can be medically downgraded, which is a risk that comes with speaking out, depending on the area you work in. A lot of people feel stigmatised for speaking out, so it’s good to see help-seeking normalised.”

Bethesda focus

Bethesda focus

While Richard has been working with clients at Veteran Central in ANZAC House he has recently taken up on of the role of the director of the Military, Veteran and First Responder Program for Bethesda Clinic, which opens in Cockburn in September. The role oversees the development of specialist mental health inpatient and day programs for defence personnel, veterans and first responders as the clinic will have a strong focus on bespoke mental health services for this group.

Richard is developing programs specific to assisting individuals and their families who have sustained physical and/or psychological trauma in the line of duty.

“What ANZAC House does, and Bethesda will do, is provide an integrative service to bring together care such as dental, psychiatry and appointments for ears and skin or referrals to art therapy or something which helps engage with society.”

For example, Richard may work with someone who has anxiety and who might grind their teeth and need dental treatment. Having a system at a location where a person can access each specialist is hugely helpful. First it means someone can be treated faster, plus they don’t have to keep repeating their story, which in these cases can be painful and triggering.

While his own military service gives Richard insight into the lives and mental health of the patients, he says it doesn’t necessarily result in immediate trust from his patients, but there’s definitely a level of rapport that comes from having been in similar situations.

“Veterans are very loyal and if they have found a place of support, they will push their colleagues towards it.

“These are people who go in the direction of danger when everyone else runs the other way. They are brave and successful and come here asking for help. If you can convince them you are going to help them better understand themselves, link them to support and encourage things like exercise rather than just throwing drugs at them, that’s how you win them over.

“Plenty of people come out of the military and crush it. But others find dealing with these details causes significant anxiety.”

Military life is set out and runs to a schedule. When you leave it’s a case of relearning and retraining yourself around so many things, including some of the seemingly insignificant things such as what time you get out of bed.

Holistic care

Richard is excited about what the Bethesda facility will offer, particularly for the local community in the southern suburbs. He’s also enthusiastic about the rounded medical care being offered alongside more novel aspects such as prescribing a sensory diet, if that’s a better option than drugs. Or a green prescription – exercise and movement – if that will help alleviate an issue.

“If our first treatment step is to use drugs, then that informs our whole culture,” he says. “You have to get the setting right. I prescribe exercise as medicine and trauma-informed yoga with all my patients.”

Daily exposure to other people’s trauma stories means Richard must consistently tend to his own mental health. As a dad and husband, like his patients he wants to be consciously present in their lives.

While walking the dogs is relaxing, getting into the garden at home is one of his biggest pleasures. The Magtengaard veggie patch is bountiful enough that it feeds the family of four a couple of meals a week. Richard’s eldest is a budding chef and makes a mean pasta dish fresh from the garden.

“I get to spend my whole day having interesting conversations with cool people,” says Richard. “It’s a privilege to hear about someone’s hard time. And it’s also great to hear they’re not yelling at their kids anymore. You’re getting to help them repair a rupture.

“I admire these people for their strength. I don’t know how they do it – and I don’t know if I would be that stoic.”

Now in his 50s, Richard believes it is a time in life when you think about leaving your world in better nick. This is his way of doing that.

He’s found an ally in fellow veteran Dr Rory Morris-Butler, a retired British Army Medical Officer. His work at London’s Maudsley psychiatric hospital and during a fellowship in Canberra showed him the experience of working in military psychiatry in the UK could benefit Australian veterans.

The pair share a passion and understanding of veterans’ sometimes unique experiences and needs. Together, Richard feels they can offer a special level of care and understanding underpinned by gold standard evidence-based care and a holistic approach.