The components of the standard comprehensive lipid panel – total, LDL- and HDL-cholesterol along with triglycerides – are well-known, as is the role of LDL-cholesterol as a key cardiovascular risk factor and target for risk-reducing therapy.

Other, somewhat unintuitively named lipid-related tests (apolipoprotein-B, apolipoprotein A-I, apolipoprotein A-II, LDL subfractions, and others), while useful in some patients, are likely to remain outside the mainstream. Lipoprotein(a), commonly abbreviated to Lp(a) and pronounced “lipoprotein-little-a” or “L-P-little-a,” is an exception that is nearly certain to gather pace as a part of routine clinical care in the near future.

Lp(a) is similar in size and structure to LDL, but carries a protein called apolipoprotein(a), which imparts additional atherogenic and prothrombotic effects. Its plasma concentrations are highly genetically-determined, more so than LDL, with relatively little influence from diet, exercise, and other environmental factors.

Its production and clearance pathways, while not fully understood, are distinct from those of LDL. This is partly evidenced by the fact that statins, which upregulate the clearance pathway for LDL particles, do not decrease Lp(a).

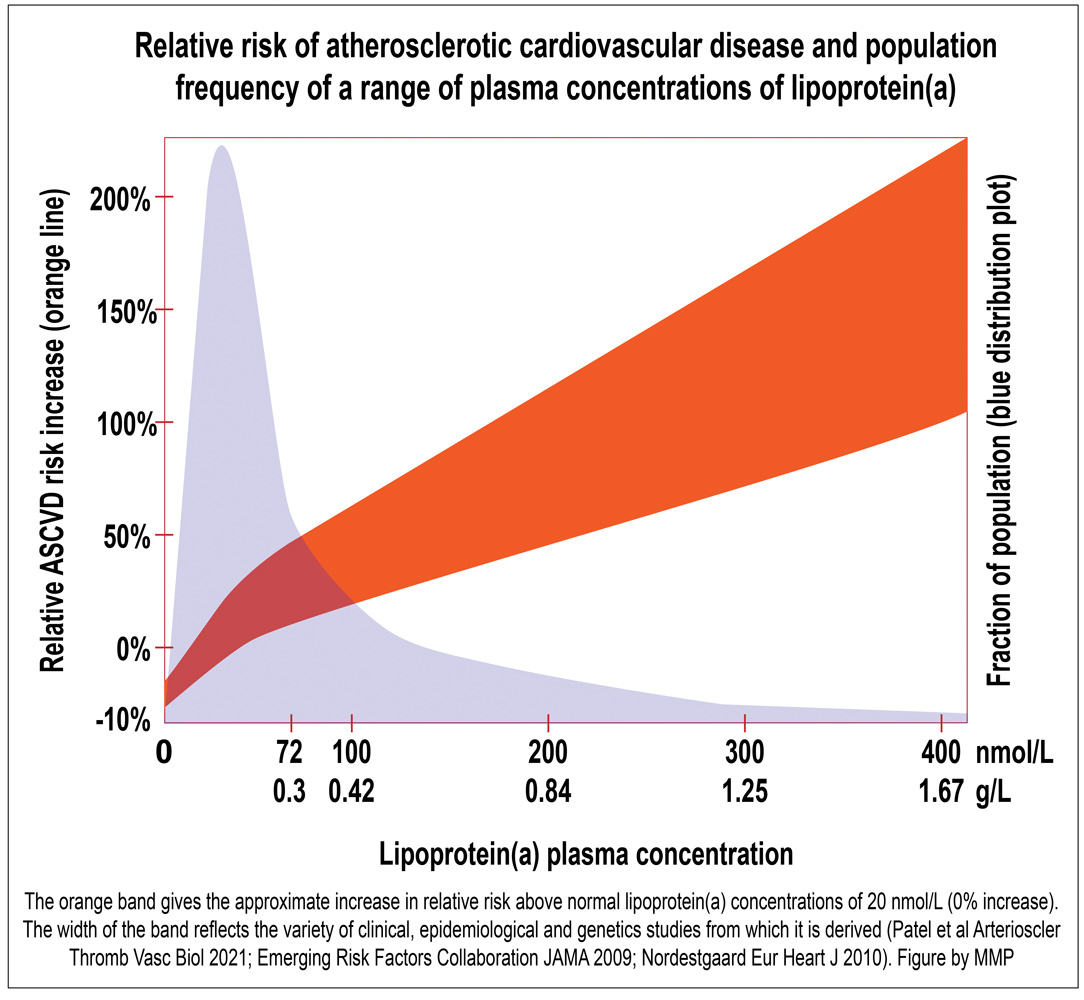

The atherogenic nature of Lp(a) is beyond doubt, based on large studies using the genetic technique of Mendelian randomisation. The relative risk of coronary artery disease is increased by at least double with very high concentrations of Lp(a), and perhaps significantly more (see Figure).

On this basis alone, some international guidelines have recommended that Lp(a) should be tested at least once in every adult’s lifetime. Others advocate testing Lp(a) in patients with other risk factors including premature atherosclerotic disease.

An unusual property of Lp(a) – that people with lower concentrations tend to have larger particles, and those with higher concentrations tend to have smaller particles – makes the accurate measurement of Lp(a) a unique challenge. As a result, not all Lp(a) assays available in Australia are highly accurate across the range of possible concentrations. Furthermore, some assays are calibrated to mass units (g/L or mg/dL) and others to molar units (nmol/L). The latter, which better reflects the number of Lp(a) particles, is more likely to become the measurement unit of choice.

In the meantime, some laboratories report mass units, some molar units, and some provide both on the report. However, direct conversion between mass and molar units is unreliable owing to the variable mass of Lp(a) particles.

In the meantime, some laboratories report mass units, some molar units, and some provide both on the report. However, direct conversion between mass and molar units is unreliable owing to the variable mass of Lp(a) particles.

Until effective Lp(a)-lowering therapies become available, treatment recommendations for patients with high Lp(a) centre on other risk-reducing strategies such as initiating or escalating statin therapy and paying close attention to other cardiovascular risk factors. Patients with very high levels may be considered by lipid specialist clinics for enrolment in clinical trials of novel Lp(a)-lowering therapies or even Lp(a)-apheresis, a process of regularly “filtering” Lp(a) from the circulation.

Whether therapeutically lowering Lp(a) reduces cardiovascular risk should first be answered in about 2024 by the results of a large randomised controlled trial of pelacarsen, an antisense oligonucleotide that degrades the mRNA that encodes apolipoprotein(a), thereby preventing the formation of Lp(a) particles.

Given subcutaneously once per month, it persistently lowers Lp(a) concentrations by about 80%. The results of the trial are keenly awaited.

There is not yet a Medicare rebate for the measurement of Lp(a). The out-of-pocket cost for the test is typically less than $50.

Key messages

- Measuring lipoprotein(a) for cardiovascular risk assessment is gaining prominence, particularly as lipoprotein(a)-lowering therapies advance through clinical trials

- Lipoprotein(a) is similar to LDL but has unique additional atherogenic properties, different clearance pathways and is not reduced by statin therapy

- Until specific lipoprotein(a)-lowering therapies are available, management of elevated lipoprotein(a) centres on other risk-reducing strategies, although high-risk patients may be considered for investigational agents or lipoprotein(a)-apheresis.

Author competing interests – the author has received consulting fees from Novartis.