Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in Australia, for both men and women, with new cases numbers rising each year. Lung cancer causes more deaths than breast, colorectal, and cervical cancers combined – cancers for which national population-based screening programs already exist.

Survival rates from lung cancer are low because it is usually late-stage disease by the time of diagnosis. The key to improving the length and quality of life of Australians with lung cancer is to diagnose it earlier.

In 2019, the Australian Minister for Health, Greg Hunt, requested that Cancer Australia inquire into the appropriateness, feasibility, and potential process of a national lung cancer screening program. From this, an evidence-based lung cancer screening program plan (the Program) was designed to maximise the benefits and minimise the harms of screening. It would mirror and complement the other national cancer screening programs.

It was found that such a screening program would reduce lung cancer mortality in Australia by at least 20% in the screened population and improve the quality of life of Australians affected by lung cancer. It was estimated that in the first 10 years of such a program, more than 70% of screen-detected lung cancers would be diagnosed at an early stage (currently less than 20% are), over 12,000 deaths would be prevented and up to 50,000 quality adjusted life years would be gained.

The recommendation for a program received widespread support in the medical and lay communities.

International experience

Two large and well-designed trials of Low Dose CT-screened (LDCT) versus non-screened long-term cigarette smokers in the US and Europe both showed a substantial reduction in disease-specific mortality.

In the UK, targeted LDCT screening programs have been introduced in Liverpool and Manchester. In the US, screening has been introduced at about 2000 centres, albeit with no national registry, generally relying on the American Thoracic Society and American Lung Association protocols. Lung cancer screening is also being trialled or implemented in Canada, Spain, Poland, South Korea, Brazil and Israel.

Currently in Australia a modicum of “case finding” with LDCT is conducted by GPs and specialists. There is no organised population screening program for lung cancer. The Cancer Australia proposal would be a federal program delivered with the cooperation, input and support of state and territory governments.

False positives and negatives

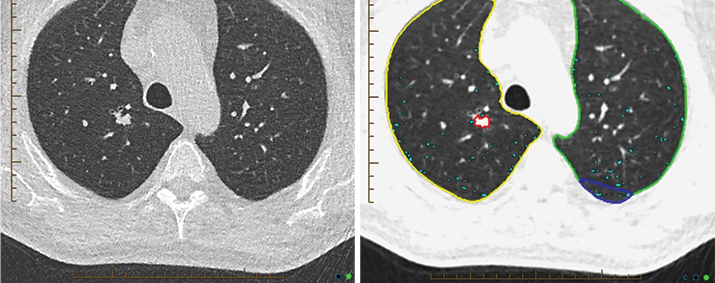

Using volumetric (instead of a simple diameter) measurement of nodules in the more recent European trials reduced the rate of false positives substantially (only 1.2% in the largest European trial). Volumetric measurement will be required in the Australian program to reduce the false positive rate as well as unnecessary invasive procedures, biopsies and surgeries.

The reported rates of false negatives in international trials are low (1%) and are therefore not considered a significant problem for LDCT screening.

The current best estimate of overdiagnosis is 8.9% (11-year follow-up). In the Australian program, rates of overdiagnosis will be minimised using a risk assessment tool for eligibility, performing volumetric analysis in concert with advanced nodule characterisation techniques such as artificial intelligence, and utilising contemporary nodule management strategies.

LDCT scans are purposed for nodule detection and not, for example, mediastinal pathology. They are typically less than 1.5mSv though with the most advanced technology substantially less. For comparison, annual background radiation is approximately 2.5mSv. Modelling of dose exposures indicates there will be only a minor risk of significant long-term biological harm to participants. The benefits of LDCT screening for lung cancer will far outweigh potential harms.

Other harms include morbidity or mortality from downstream investigations or treatments. The compelling international evidence supports the conclusion that such harms are uncommon and usually manageable and should be considered in the context of substantial improved survival rates.

Going forward

The population cohort for the Australian program is proposed as current or former smokers aged 55 to 74 years. An internationally validated risk assessment tool, called the PLCOm2012 (Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer) model, will be applied to people on entry to the program to assess their suitability. This tool requires the age, ethnicity, education, personal and family history of cancer and smoking status and smoking intensity of each patient. This PLCO model has performed well in validation studies and is promoted in most international screening guidelines.

For most patients, the likely referral pathway will be through their General Practitioner. The referrer will be responsible for obtaining informed consent. Other entry points may be self-referral or organised entry (a potentially eligible participant is proactively identified from existing medical records).

It was proposed that current smokers entering the program be encouraged to access a smoking cessation education program. There is evidence that trial participants who are educated at this opportunity have higher quit rates than the general population of current smokers.

The program will require radiology providers to adhere to national quality control standards and report data to a centralised register for monitoring key outcomes, quality assurance and research purposes. It is expected that the radiologists’ LDCT readings will be complemented by artificial intelligence (AI) to improve accuracy for detection and characterisation of nodules. Incidental findings will be managed in accordance with contemporary clinical practices.

It is anticipated that the human, machine, and other resources demanded by the program will be met by the existing workforce and infrastructure. The total program costs are estimated to be $127 million in the first year, reducing to $76 million by Year 4. The estimated cost-effectiveness ratio is $83,545 per QALY gained. This compares favourably to the other government-sponsored screening programs.

The prospect of screening Australians at risk of lung cancer with LDCT is heartening because, if implemented carefully and handled well, it could manifest a remarkable increase in the length and quality of life of sufferers, at a reasonable cost.

As with other cancer screening programs, GPs will be central to the uptake and success. A successful program will also require dedication from multidisciplinary teams of specialists with adherence to national quality assurance guidelines as well as monitoring and reporting requirements.

Key messages

- Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death

- Following an inquiry, a screening program has been proposed

- It could increase survival and quality of life for those with lung cancer.

– References available on request

Author competing interests – nil