Former copper Rob Atkins has used his own story with PTSD to co-write a book to help others talk to their families about this significant mental health issue.

By Ara Jansen

Rob Atkins calmly explains that he was sitting on a hill, with a rifle. At that moment, his faithful assistance dog poked his head through the crook of Rob’s arm and licked his face. He came back to himself and took a deep breath.

“I decided not to kill myself that day,” says for the former police officer. “My dog was a lifesaver.”

When dealing with his own PTSD, Rob later told his wife they should write a book about how to share the mental health condition with the kids because there didn’t seem to be one for first responders.

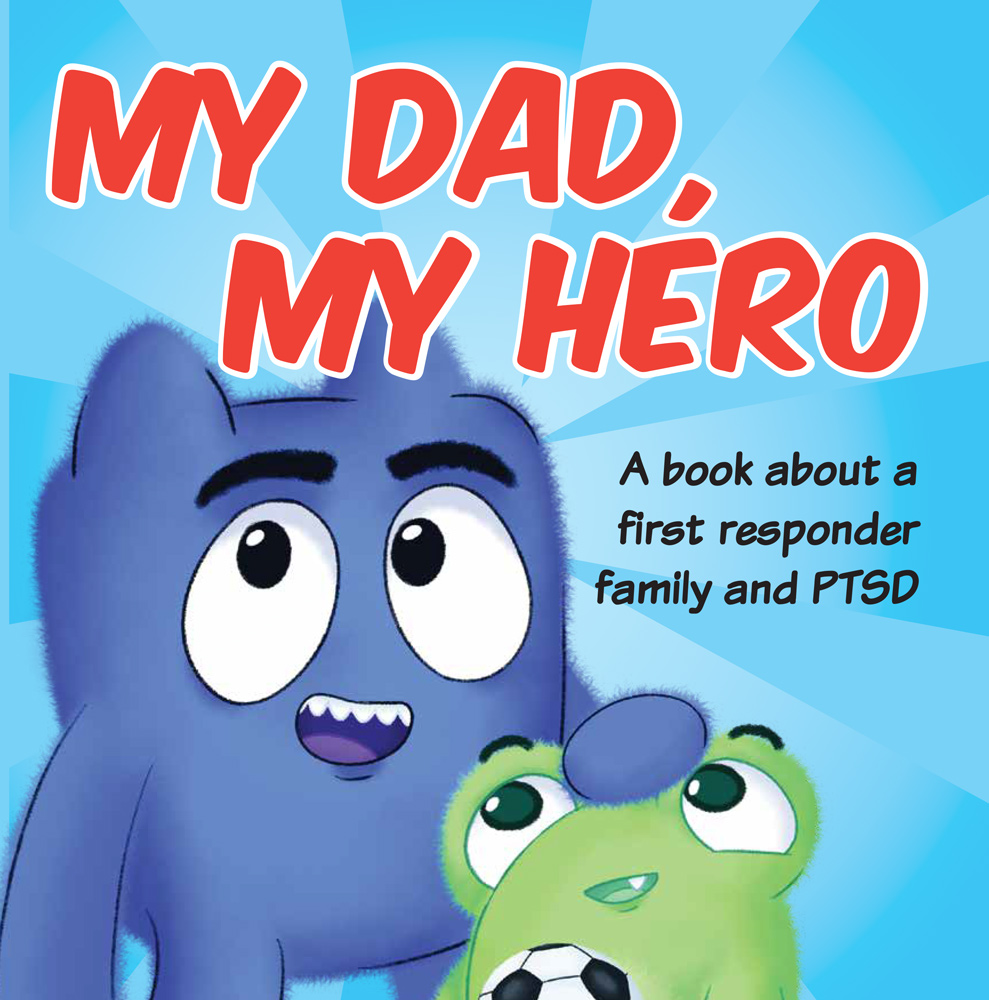

At the time it was a throwaway line, but three years later, My Dad, My Hero has been released. It’s a children’s book designed to help families of first responders open up conversations about post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other mental injuries.

With the help of experts, Rob and his wife Chrysti have written the book which can be read with parents for kids in primary school, or independently for slightly older readers.

Ten per cent of professional first responders experience PTSD and similar mental health challenges due to the nature of their work, so the book provides an accessible and compassionate resource for children and families to understand these often-complex issues.

Professional first responders – firefighters, police, ambulance and 000 operators – face extraordinary pressures in the line of duty. The mental toll of witnessing and hearing traumatic events can lead to long-term emotional injuries, affecting not only the individuals but also their loved ones.

The book helps bridge the gap in understanding by explaining PTSD and its impact in a way that is approachable for children, gentle and compassionate.

The book helps bridge the gap in understanding by explaining PTSD and its impact in a way that is approachable for children, gentle and compassionate.

Rob was a police officer of 24 years and a soldier for six years before that, including peacekeeping in the Solomon Islands. He has cumulative PTSD (CPTSD), which he describes as death by a thousand cuts, resulting from prolonged trauma.

In his case, it was working as a police officer in Victoria and watching daily human carnage, violence and aggression, then later going home where his kids would want to play, but he was often too angry.

“Children often feel like it’s their fault,” says Rob. “Through the book we’re keen for kids – and the partners of first responders with PTSD – to know that they are not alone.

“Writing the story was quite easy but what was hard was finding the correct language, so we got some help from two psychologists to make sure we were on the right track.

“While my boys are now 16, 19 and 21, this is the book I would have wanted to share with them when they were little. I have a tremendous amount of guilt about the pain and fear I cost my family.”

Rob recalls that as a dad to his young boys he thought he was “killing it”. When the boys ran to greet him at the door when he arrived home, he didn’t realise they were testing to see if he was in a bad mood. If he was in a good mood, they’d play together. If not, the kids would run and hide. Rob says he now knows why they were always wondering what version of dad they would get – angry dad or fun dad.

“I became more and more the angry dad who walked through the door. With this book we wanted families to know they are not alone. For quite a long time I couldn’t read it without crying because I felt so much guilt.

“I became more and more the angry dad who walked through the door. With this book we wanted families to know they are not alone. For quite a long time I couldn’t read it without crying because I felt so much guilt.

“This book is a communication tool for parents to start a conversation. Showing the kids it’s not their fault and they haven’t done anything wrong. After the story, the second part of the book offers things mum and dad can do to help themselves feel better. For example, kids can encourage their parent to go out for some exercise, that maybe they can do together.”

The book has been published by Victorian-based The Code 9 Foundation as a fundraiser with a serious message. The foundation – cofounded by Rob – provides a place of support for current and veteran professional first responders and 000 operators who live with PTSD, depression, anxiety and other mental health conditions that result from their service to the community. Code 9 in Victoria is the call signal for an officer in trouble.

Among other initiatives, the foundation funds a number of assistance dogs each year, meals and home support, respite weekends and a camp for teens in households with a parent with PTSD. They have around 3500 members in their private forum across the country.

Copies of My Dad, My Hero are available in paperback for $22 at www.code9ptsd.org.au and www.mydadmyhero.com.au