ED: No-one wants later deformity from childhood trauma to the elbow. Timely advice or intervention from an experienced orthopod is handy if you can get it.

Paediatric elbow injuries are relatively common and amongst the most challenging and difficult injuries to treat. Prompt recognition and appropriate first aid management is essential which requires accurate clinical assessment and interpretation of plain films and where needed, paediatric orthopaedic referral.

Functional anatomy

A “simple” hinge joint, the elbow is kept stable by a complex combination of bony articulations and medial and lateral ligaments. Various ossification centres around the elbow can create confusion and can be mistaken for fractures. Try the CRITOE mnemonic for their appearance:

C – Capitellum (1-2 years of age)

R – Radial epiphysis (3-5 years)

I – Inner epicondyle (medial epicondyle; 5-7 years)

T – Trochlea (7-9 years)

O – Olecranon (9-11 years)

E – External epicondyle (lateral epicondyle; 11-13 years)

Ossification centres later fuse to their relative bones between the ages of 14-18 years (girls roughly two years prior to boys) until then, ‘if in doubt, X-ray the other side’ is a helpful saying.

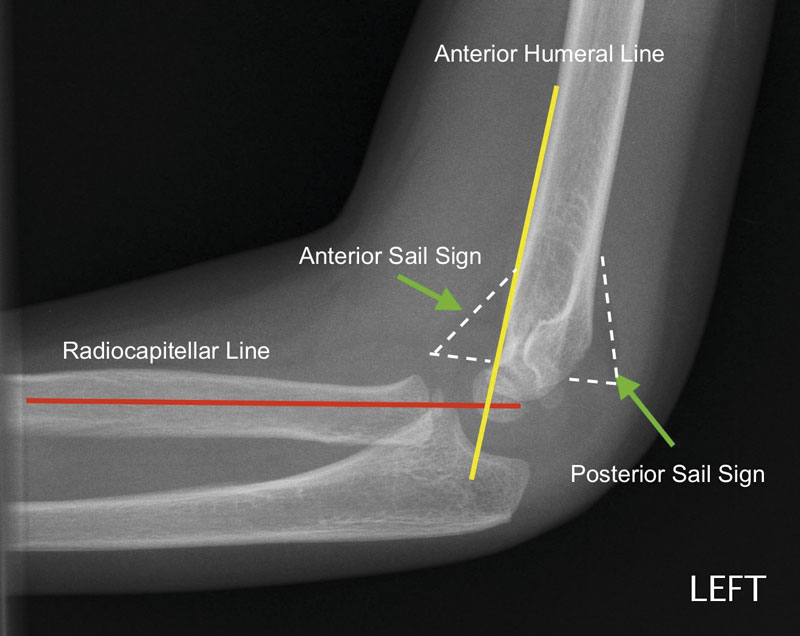

With X-rays, identification of anterior or posterior “sail sign” (Figure 1) is important. If present, it represents a joint effusion or haemarthrosis. Why is this important? Children rarely “sprain” ligaments; they either avulse them or fracture bones. After trauma, a sail sign indicates an occult fracture, and appropriate immobilisation should be undertaken.

Pulled elbow (Nursemaid’s elbow)

Usually before the age of five, this injury is secondary to longitudinal traction of the arm with the elbow extended e.g. a parent grabbing the arm of their falling child or pulling the child by the hand. The annular ligament subluxes over the radial head and becomes entrapped within the radiocapitellar joint. There is pseudo-paralysis of the affected limb, with the arm usually hanging in extension and pronation.

Treatment of this injury is appropriate in the office: with a thumb over the radial head, reduce with forced supination and flexion of the elbow; often a palpable click is felt and pain relief is almost instantaneous.

Lateral condyle fracture

Not complex to manage, this fracture is often difficult to identify. Failure to recognise and immobilise a non-displaced lateral condyle fracture can lead to non-union (with later cubitus valgus and ulnar nerve palsy). Unless completely undisplaced, these fractures are usually stabilised surgically and so should be referred appropriately.

Monteggia fracture/dislocation

This injury combines a proximal ulna fracture with a radial head dislocation. Some are exceeding obvious, whilst some may be quite subtle with mild plastic deformation/bowing of the ulna shaft. The key to diagnosis is to ensure that the radial shaft/head aligns with the capitellum on all views (Figure 1).

Whereas most acute injuries can usually be managed with simple manipulation and immobilisation, late-presenting Monteggia fracture/dislocations are more of a challenge, requiring open reduction, osteotomy and/or ligament reconstruction.

Elbow dislocation (+/- medial epicondyle fracture)

Elbow dislocations are not uncommon amongst sporting adolescents. Most are simple dislocations, managed in the ED with closed reduction under sedation.

However, in children, associated fractures of the medial epicondyle are not infrequent.

Initial management of this injury is still emergent reduction of the elbow, but care should be taken to ensure a congruent reduction post manipulation as there is a risk of incarcerating the medial epicondyle within the joint. If there is any doubt about the adequacy of reduction or the previously visualised medial epicondyle fracture can no longer be seen, there should be a low threshold to post-reduction CT.

Supracondylar humeral fractures

The most common and potentially serious paediatric elbow injury is the supracondylar humeral fracture. These injuries are usually the result of significant trauma where a child has fallen on an outstretched arm. Depending on the mechanism of trauma and fracture displacement, they are commonly associated with neurovascular compromise. As such, careful assessment of distal neurological function and vascular perfusion is essential.

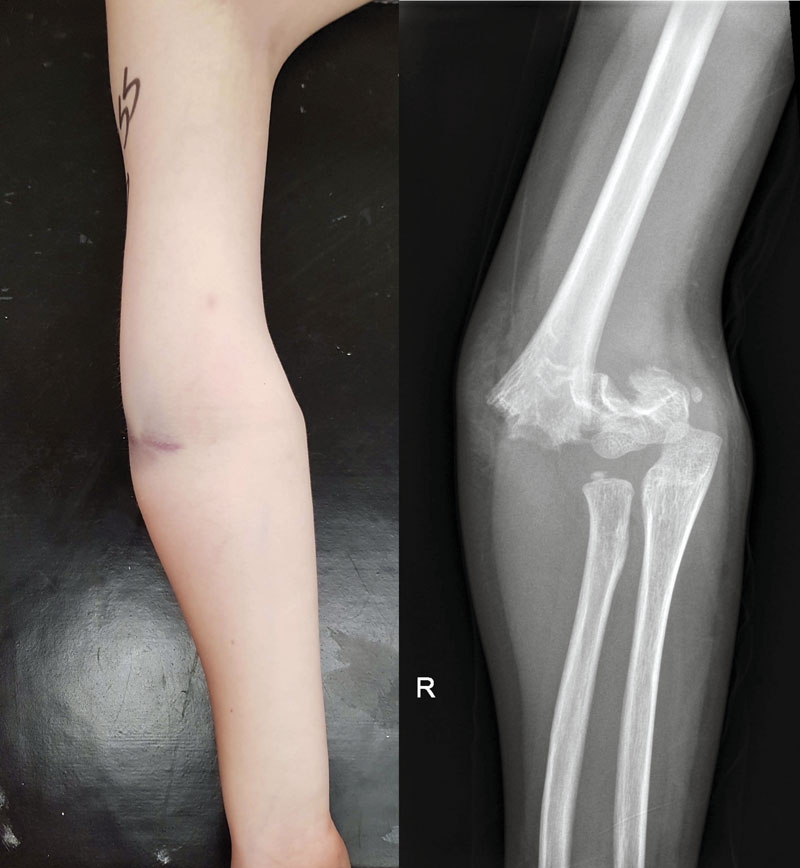

Other important clinical findings include clinical deformity, swelling, and anterior bruising or “puckering” of the skin (indicating the anteriorly displaced humeral shaft has impaled the brachialis to the skin) (Figure 2). Rarely, these injuries can be open fractures. In addition, care must be taken to exclude a forearm or wrist fracture in the same arm. Any of these signs indicate a high energy mechanism for which a high suspicion of possible neurovascular complications or compartment syndrome is warranted.

Radiologically, occult fractures can be diagnosed by the presence of a sail sign. Minimally displaced fractures can be identified on the lateral x-ray, with the anterior humeral line running in front of the capitellum (Figure 1).

Unless undisplaced, most of these injuries require orthopaedic input. Initial first aid includes analgesia, accurate assessment of neurovascular status and splintage (not the usual 90 degrees of elbow flexion but as for most elbow injuries but in a position of comfort for the child, which is usually relative extension). Any attempt at manipulation in the emergency department, regardless of the state of vascular perfusion, is not advised due to the risk of further damage. A cold, pulseless hand is an orthopaedic emergency.

Key Points

- Knowing the age relevance of various ossification centres around the elbow can minimise confusion.

- Accurate clinical and radiological assessment is the key to appropriate management.

- Orthopaedic referral as appropriate (if in doubt, immobilise and seek orthopaedic opinion).

References available on request.

Questions? Contact the editor.

Author competing interests: nil relevant disclosures.

Disclaimer: Please note, this website is not a substitute for independent professional advice. Nothing contained in this website is intended to be used as medical advice and it is not intended to be used to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease, nor should it be used for therapeutic purposes or as a substitute for your own health professional’s advice. Opinions expressed at this website do not necessarily reflect those of Medical Forum magazine. Medical Forum makes no warranties about any of the content of this website, nor any representations or undertakings about any content of any other website referred to, or accessible, through this website.