If the latest clinical research holds true, Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy (PAT) could revolutionise our understanding and treatment paradigms for mental illness.

Psychedelics are psychoactive compounds which impact our subjective experiences, allowing people to work through emotional conflicts and traumas which underlie and fuel mental illness. The neural correlates of these experiences are understood. Massive neuroplasticity and reorganisations are triggered by serotonin 2A receptors in the neo-cortex. These non-patentable compounds are unattractive to big pharma, leaving research and ‘marketing’ largely to not-for-profits and forward-thinking universities.

Psychedelic compounds are mostly found in nature, in fungi, plants and a few animals. They have been used by humanity as sacred healing compounds for millennia. The Nixon government’s ‘war on drugs’ led to these compounds being unscientifically banned in 1971. More recently, LSD and MDMA were synthesized in laboratories, and the search for synthetic psychedelics with clinically useful properties continues.

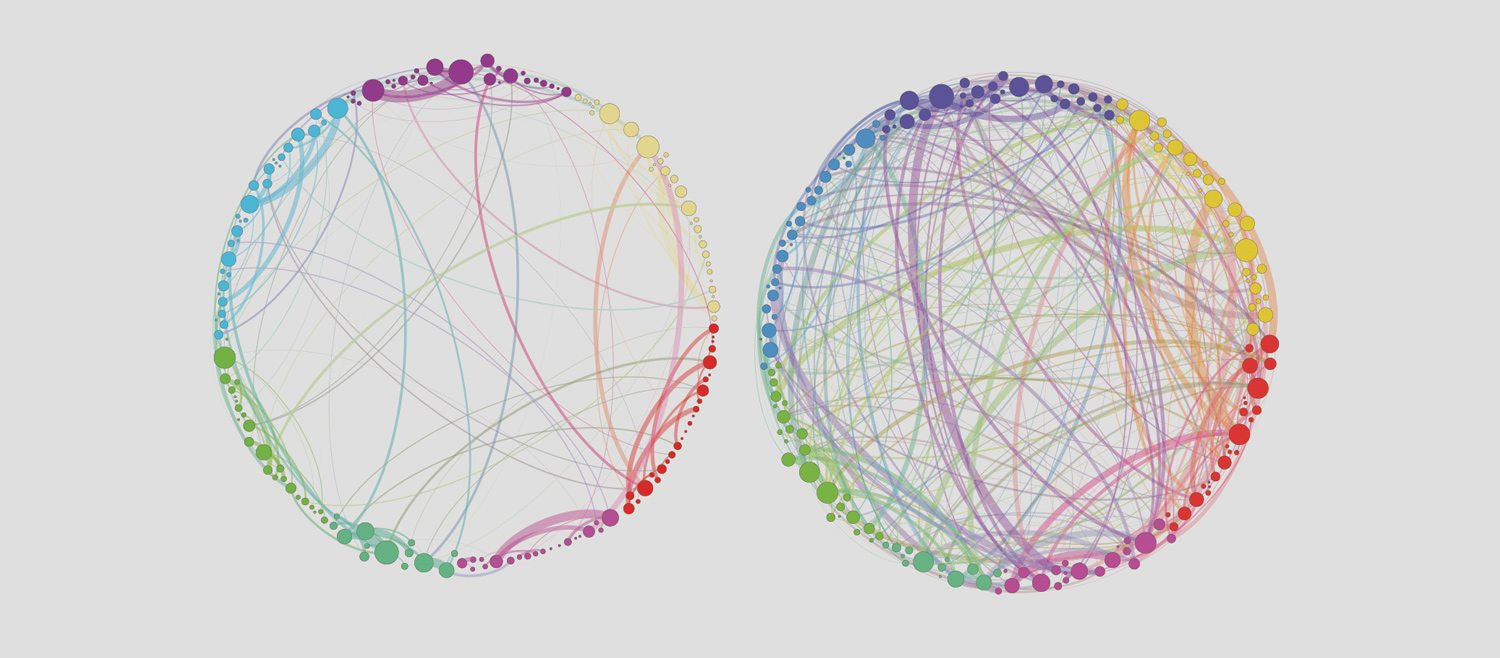

Psychedelics appear to work through serotonin-2A receptors in the neo-cortex. These receptors radically increase the connectivity between cortical neural networks which usually don’t talk to each other. This increases entropy in the brain, “dissolving” previously hard-wired and rigid connectivity.

Focus has been placed on the Default Mode Network (DMN), a ‘resting-state’ neural network correlated with self-referential thoughts and musings (like ‘ego’). 5HT2A receptors trigger neuroplastic changes, both functional and structural. These neurological shifts and events correlate nicely with the phenomenological experience of patients taking psychedelics.

The subjective experiences of patients include ego-dissolution (breaking down thought-filled, controlling, and rigid aspects of our minds), connection, access to emotions, memories and conflicts, access to unconscious material, and a reorganisation of previously firmly held beliefs about oneself and the world. Often difficult and challenging initially, like any good therapy, it is through the shadow, fear, and pain that true healing is found.

The subjective experiences correlate with therapeutic efficacy. This is fundamental in the mechanism of action of psychedelics and underlies their paradigm-shifting potential in treatment of mental illness. Often, psychiatric medications treat the symptoms by removing them (e.g. fear, anger, sadness). Psychedelics appear to work by giving us the courage to face disturbing parts of ourselves and work through them.

Thus, psychedelics are prescribed in the context of therapy. PAT is a new paradigm in which the power of a medication enhances good therapy to create a powerful modality of treatment allowing people to work through the underlying emotional conflicts and traumas, which may have triggered and maintained their mental illness. Patients say it can be akin to having a decade of therapy in a month.

In this paradigm, mental illness can be seen as a symptom, a manifestation of unresolved emotional conflict. Most people with chronic treatment-resistant mental illnesses had difficult developmental experiences, or other trauma. This can be ignored in our current paradigms, which focus on syndromes often at the cost of the individual’s personal narrative (what is different in this person?). Carl Jung forewarned that this approach to mental illness would jeopardise patients.

Over 160 current and recent trials demonstrate effect sizes well in excess of current treatments. In a series of MAPS Phase 2 trials with 105 participants (PTSD for average 18 years), 52% went into remission immediately after just three medicinal sessions combined with psychotherapy, and 68% after 12 months. Most of the remaining 32% had clinically significant decreases in symptoms. A phase-3 trial by MAPS will soon be published and preliminary results are even better.

Recent research found 68% of patients in remission from moderate to severe depression at six weeks after two sessions of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy versus 34% taking daily escitalopram combined with psychotherapy. Psilocybin had quicker effects of greater magnitude in reducing depressive symptoms and was well tolerated. Anxiety and suicidal ideation were also reduced significantly.

Numerous smaller open-label trials have had similarly outstanding results in a broad range of conditions. A trial of 15 chronic smokers had a 60% remission rate from nicotine at 2.5 years after a few sessions of psilocybin in addition to basic CBT. A similar trial of 14 subjects for alcohol use disorder found at nine months post eight-weeks of therapy including 2 MDMA sessions, only 21% of participants were drinking more than the recommended daily intake, and nine were abstinent, compared to 75% of participants who were subject to Treatment as Usual.

Equally impressive results have been found in death-related anxiety (up to 80% response) in those with terminal illnesses. The Canadian Government recently legalised psilocybin therapy for end-of-life mental-health treatment.

Not surprisingly, both psilocybin and MDMA have been granted ‘Breakthrough Therapy Status’ by the FDA. This rare designation is granted to medicines which are potentially significantly superior to existing treatments, to fast-track their approval.

The medicines are also being made available as treatments in the US, Switzerland and Israel through Expanded and Compassionate Use pathways. Several Australian doctors have received SAS-B approvals from the TGA (federally) for MDMA and psilocybin-assisted therapies. However, state-level regulation currently prohibits the use of these medicines for compassionate use in treatment-resistant patients.

Society needs to weigh a delicate balance. On the one hand, we have potential breakthrough treatments to heal treatment-resistant people suffering with chronic mental illnesses. People continue to suffer daily, and some may kill themselves. Without industry funding, resources are scarce to conduct large scale RCTs. On the other hand, we have standards of evidence which we have come to expect for all new treatments.

How long do we wait to allow compassionate use of these medications? How much evidence is enough? Who will push for access to these medications? Currently, due to regulatory issues (most significantly at the state level), these medications are not available to Australians. Given the suffering in our community, these questions are ethical as much as they are scientific. They demand deep consideration by all doctors caring for those with chronic mental health conditions.

Key messages

- Psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy may revolutionise mental health treatment

- Research is promising but

lacks funding - There are ethical as well as scientific questions.

References available on request

Author competing interests – the author is a director of Mind Medicine Australia