Tripping for a month may be too intense for many, but a new study from the US has shown surprising social learning benefits from consuming psychedelics.

Researchers at Johns Hopkins Medicine examined the impact of different substances on mice and found that psychedelic drugs were linked by their common ability to reopen “critical periods” in the brain when mammals are more sensitive to signals from their surroundings that can enhance social development.

Neuroscientists have long searched for ways to trigger this response and the team said that the findings, published 16 June 2023 in Nature, provide a new explanation for how the drugs work by revealing more about the molecular mechanisms impacted by psychedelics.

The team discovered that while LSD and psilocybin use the serotonin receptor to open the critical period, MDMA, ibogaine and ketamine did not.

Lead author Professor Gül Dölen explained that the length of the critical period in mice seemed to parallel the average length of time that people self-report the acute effects of each psychedelic drug – from two days to four weeks with a single dose.

“There is a window of time when the mammalian brain is far more susceptible and open to learning from the environment, but this window will close at some point, and then, the brain becomes much less receptive,” she said.

“This relationship gives us another clue that the duration of psychedelic drugs’ acute effects may be the reason why each drug may have longer or shorter effects on opening the critical period.

“The open state of the critical period may be an opportunity for a post-treatment integration period to maintain the learning state – too often, after having a procedure or treatment, people go back to their chaotic, busy lives that can be overwhelming.

“Clinicians may want to consider the period after a psychedelic drug dose as a time to heal and learn, much like we do for open heart surgery.”

In 2019, Dölen’s team found that MDMA, a psychedelic drug that arouses feelings of love and sociability, opened a critical period in mice.

At the time, she thought MDMA’s prosocial properties were the key factor, but her team was surprised to find in the current study that other psychedelic drugs without prosocial properties had a similar effect.

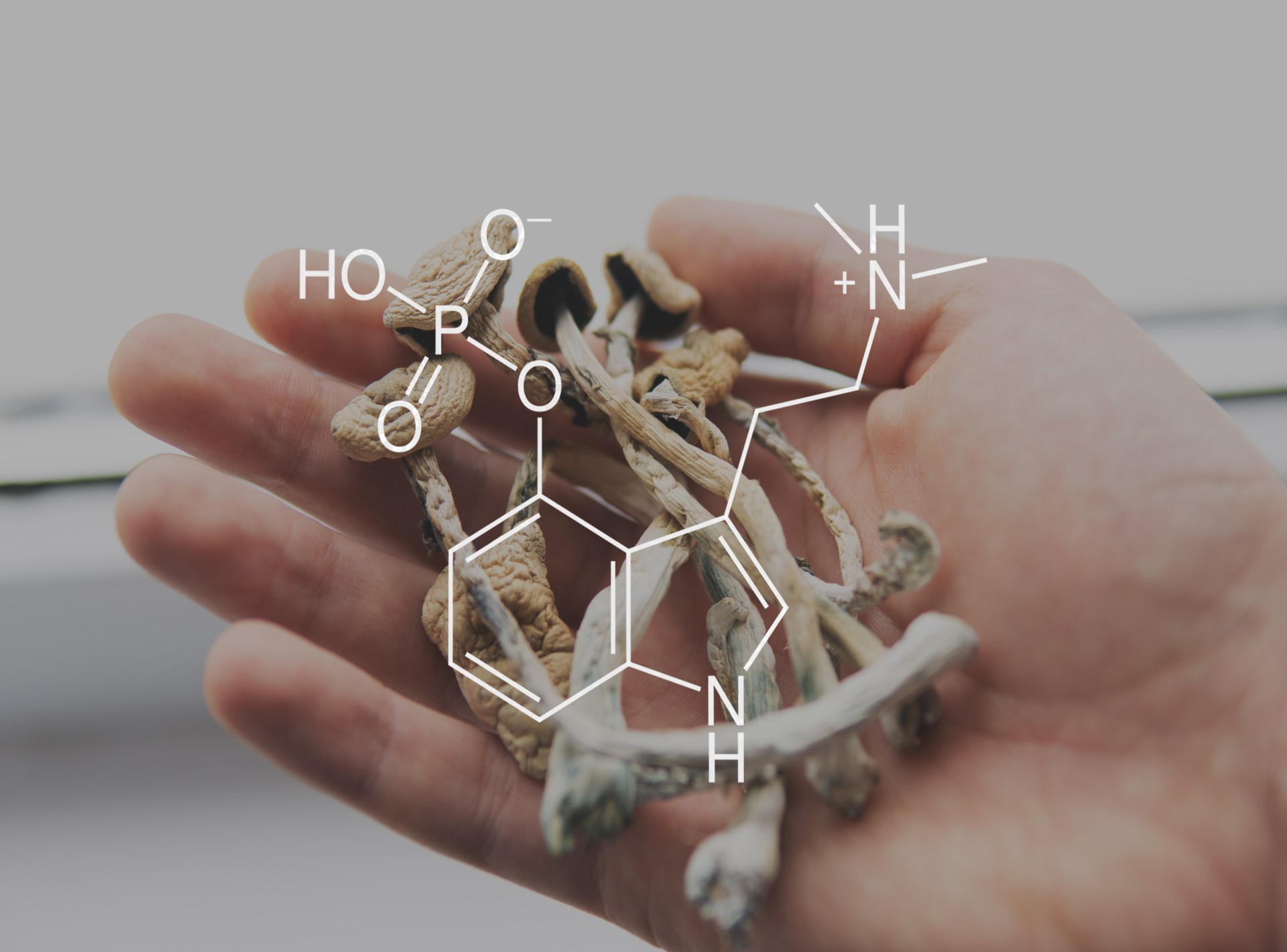

The researchers looked at the reopening potential of five psychedelic drugs — ibogaine, ketamine, LSD, MDMA and psylocibin — shown in numerous studies to be able to change normal perceptions of existence and enable “a sense of discovery about oneself or the world.”

They conducted a well-established behavioural test to understand how easily adult male mice learned from their social environment, and then trained them to develop an association between an environment linked with social interaction, versus another environment connected with being by themselves.

By comparing time spent in each environment after giving the psychedelic drug to the mice, Dölen’s team were able to see if the critical period opened in the adult mice, enabling them to learn the value of a social environment — a behaviour normally learned as juveniles.

For mice given ketamine, the critical period of social reward learning stayed open in the mice for 48 hours. With psilocybin, the open state lasted two weeks. For mice given MDMA, LSD and ibogaine, the critical period remained open for two, three and four weeks, respectively.

To explore other molecular mechanisms, the research team turned to RNA and found expression differences among 65 protein-producing genes during and after the critical period was opened, with about 20% of these genes regulate proteins involved in maintaining or repairing the extracellular matrix.

Professor Dölen believed the overall findings suggested the potential to treat a wider range of conditions beyond those in current studies of the drugs, such as stroke and deafness.

“Critical periods have been demonstrated to perform such functions as help birds learn to sing and help humans learn a new language, relearn motor skills after a stroke and establish dominance of one eye over the other,” she said.