Pterygium is common, affecting 10% of Australian adults, associated with UV light exposure. The precise pathogenesis is unknown.

Theories on cause

One theory is that light passing in a lateral to medial direction is focused by the protruding cornea onto the nasal conjunctiva leading to localised, intense UV damage.

Histologically it consists of conjunctival epithelium with hypertrophied subconjunctival connective tissue.

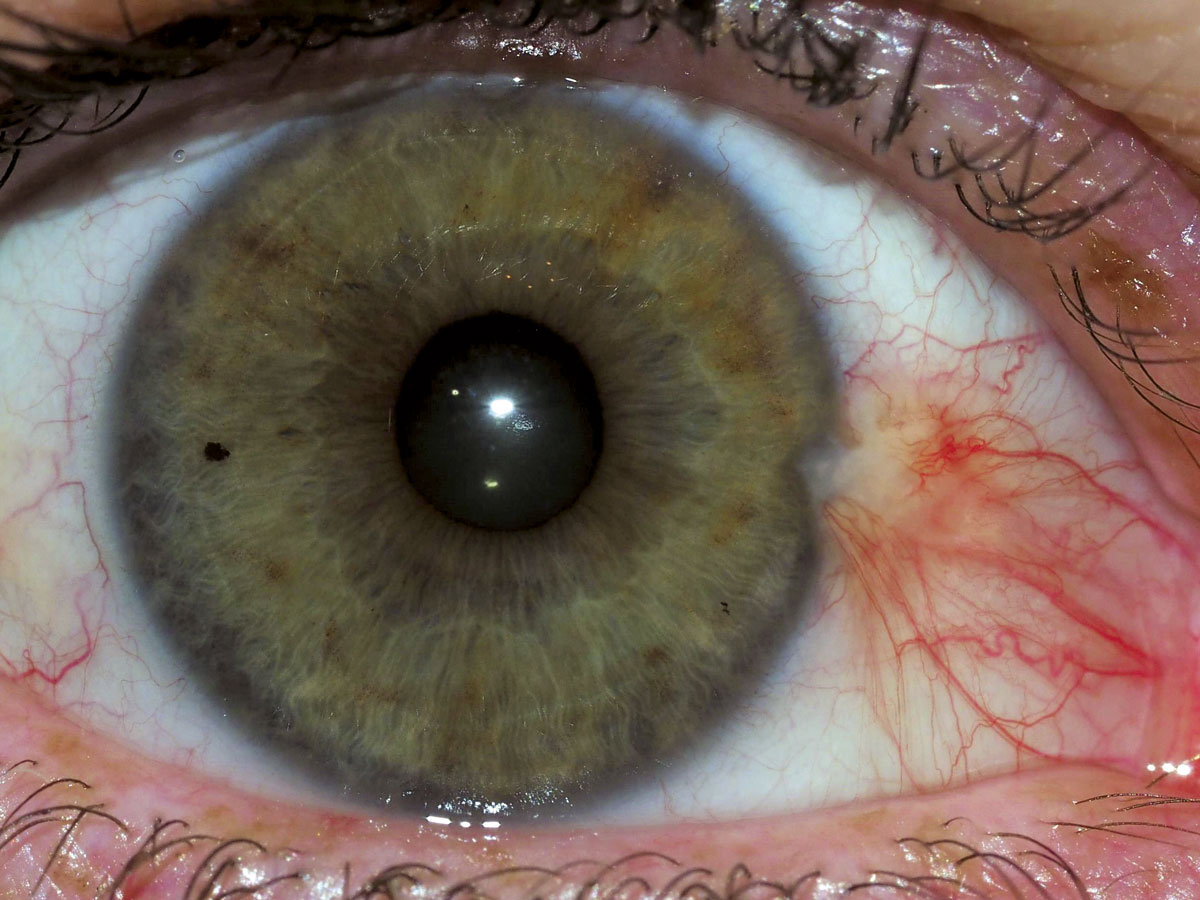

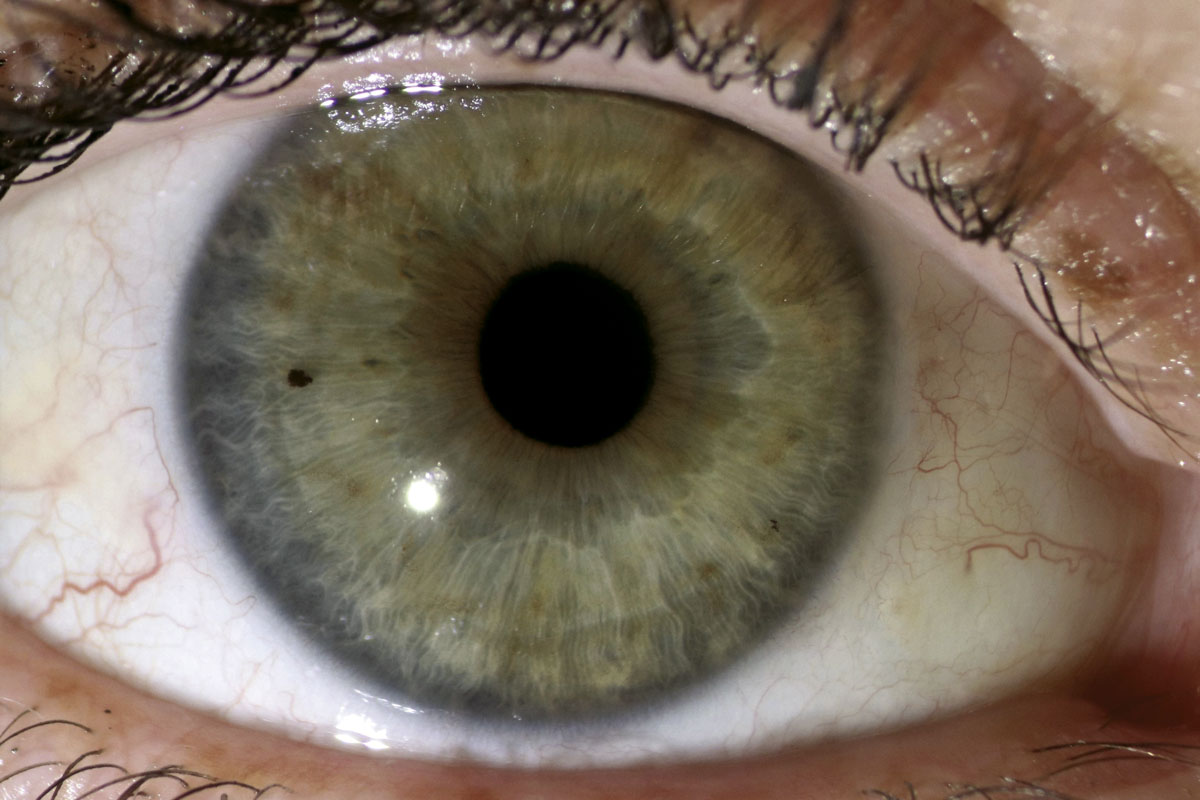

Clinically pterygia are fleshy, vascular growths which grow onto the cornea and are more common nasally. A histologically similar lesion is the pingueculum which has a pale yellow, fatty colour and is less vascular. This doesn’t extend onto the cornea.

Symptoms

Patients with pterygia often suffer irritation and chronic erythema. As the pterygium grows it distorts the cornea inducing irregular astigmatism which isn’t correctable with spectacles. When the pterygium approaches the visual axis, the vision deteriorates further because of light scatter or blockage from the pterygium itself. Rarely large pterygia can limit ocular motility and cause diplopia.

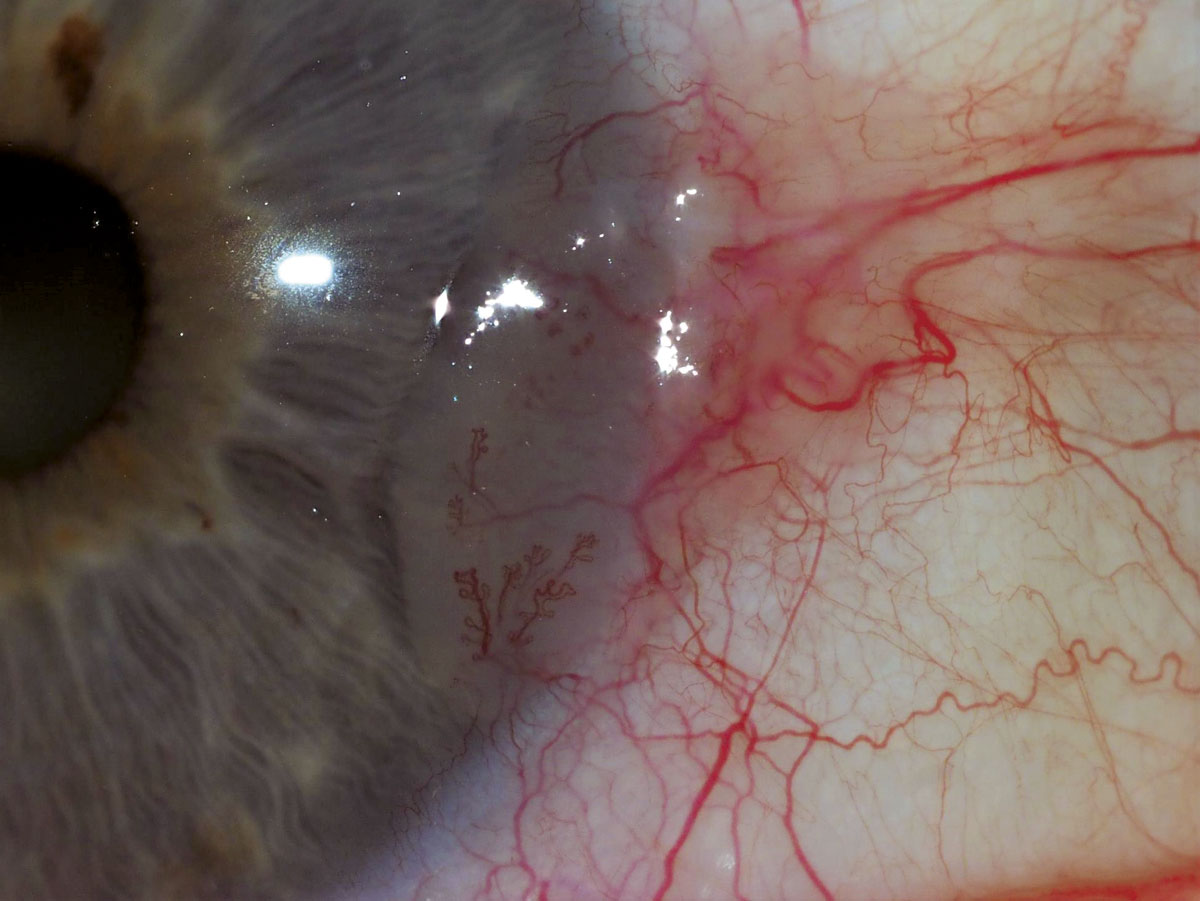

The differential diagnosis of pterygia includes pseudopterygia which are areas of conjunctival scarring on the cornea and ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN). Atypical features for pterygia include a non-nasal location, rapid growth and thickening, a gelatinous or leukoplakic surface and irregular or exuberant vascularity. Anecdotally patients which OSSN tend to be more symptomatic.

What can be done

Non-surgical options for pterygia include regular ocular lubrication and treating other ocular irritants such as posterior blepharitis and allergic eye disease. Short courses of topical steroids such as fluorometholone (FML) are appropriate; however, they shouldn’t be used long term due to the risks of raised intraocular pressure and cataract. I image all pterygiums to provide a baseline.

Surgery involves removing the pterygium and the adjacent subconjunctival connective tissue. The cornea should be left as smooth as possible.

If the defect left by the pterygium is left bare the recurrence and complication rate is unacceptably high. The current gold standard involves harvesting a thin conjunctival graft from the superior bulbar conjunctiva and securing this into the defect – a fibrin glue secures the graft and improves postoperative comfort by avoiding ocular sutures, with recurrence rate 5%.

Regional peribulbar long acting anaesthesia provides post-operative analgesia and doesn’t disturb the operative field (GA rarely required).

If a recurrence occurs, topical steroids and intralesional 5 fluorouracil are effective if used early.

Watch for mimicking squamous neoplasia

OSSN encompasses both conjunctival intra-epithelial neoplasia (in situ disease) and invasive squamous cell carcinoma – OSSN is rare but serious. Patients who are immunosuppressed, have extensive UV exposure or exposure to petroleum derivatives are at increased risk.

Impression cytology may have a role in differentiating benign from malignant lesions, however the false negative rate is high as only the surface cells are sampled. If OSSN is suspected the lesion is resected with cryotherapy to the margins.

The defect can be closed directly by mobilising adjacent conjunctiva, or amniotic membrane can be grafted into the defect to provide a basement membrane for healing. If the lesion is too large to be safely resected, or there are other contraindications to surgery, then topical interferon alpha 2A can be used, This is a well-tolerated treatment and has the advantage of providing a regional treatment to the entire ocular surface.

Key Messages

- Pterygium is common and can be managed with high patient satisfaction.

- OSSN is a rare but serious differential diagnosis.

References available on request.

Questions? Contact the editor.

Author competing interests: nil relevant disclosures.

Disclaimer: Please note, this website is not a substitute for independent professional advice. Nothing contained in this website is intended to be used as medical advice and it is not intended to be used to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease, nor should it be used for therapeutic purposes or as a substitute for your own health professional’s advice. Opinions expressed at this website do not necessarily reflect those of Medical Forum magazine. Medical Forum makes no warranties about any of the content of this website, nor any representations or undertakings about any content of any other website referred to, or accessible, through this website.