Australian researchers, led by WA’s Dr Sebastian Leathersich, have demonstrated that there is a 30% higher chance of IVF using frozen embryos being successful if the woman’s eggs are collected at a specific time of the year.

The study, published in Human Reproduction, found that the overall live-birth rate was 31 births per 100 people if eggs were harvested in summer, compared to 26 births per 100 people if they were collected in autumn.

The live-birth rates when eggs were collected in spring or winter lay between these two figures, and the differences were not statistically significant.

The researchers also found a 28% increase in the chances of a live birth among women who had eggs collected during days that had the most sunshine compared to days with the least sunshine.

Dr Leathersich, an obstetrician, gynaecologist and Fellow in Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility at Fertility Specialists WA and KEMH, explained that, until now, there were conflicting findings on the effects of the seasons on pregnancies and live-birth rates following egg collection and embryo freezing.

“It’s long been known that there is seasonal variation in natural birth rates around the world, but many factors could contribute to this including environmental, behavioural, and sociological factors,” he said.

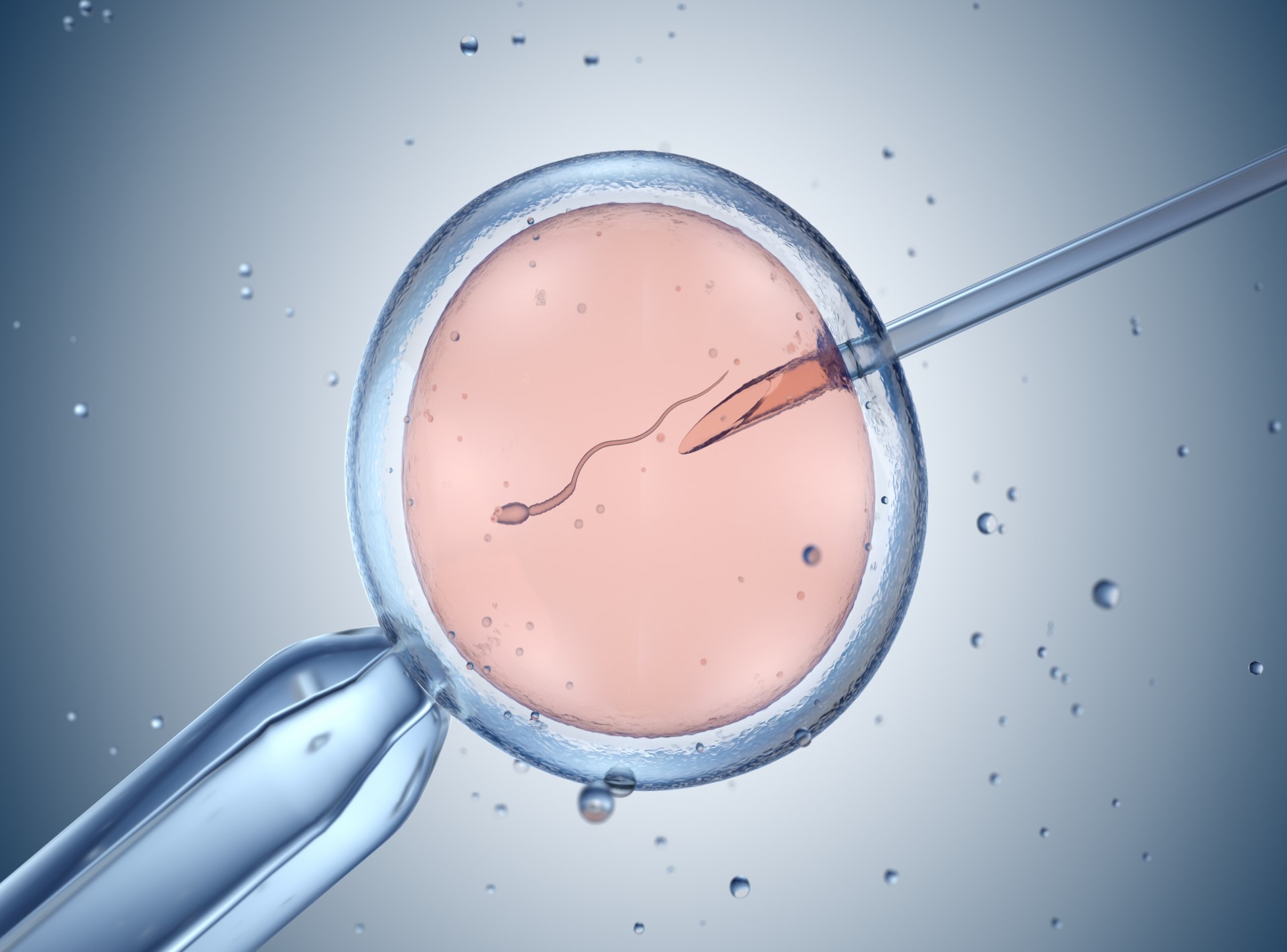

“Most studies looking at IVF success rates have focused on fresh embryo transfers, where the embryo is put back within a week of the egg being collected, and this makes it impossible to separate the potential impacts of environmental factors on egg development and on embryo implantation and early pregnancy development.

“Yet these days, many embryos are ‘frozen’ and then transferred later. We are effectively separating the conditions around egg collection from the conditions at the time of transfer, demonstrating that environmental factors when the eggs are developing are as, if not more, important than environmental factors during implantation and early pregnancy.”

Dr Leathersich and his colleagues analysed outcomes from all 3,659 frozen embryo transfers, with embryos generated from 2,155 IVF cycles in 1,835 patients, that occurred at a single clinic in Perth between January 2013 to December 2021.

Birth outcomes were examined according to season, temperatures and the actual hours of bright sunshine (as opposed to calculating hours from sunrise to sunset) using data from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology to specify three classifications: low sunshine days (0 to 7.6 hours of sunshine), medium sunshine days (7.7 to 10.6 hours) and high sunshine days (10.7 to 13.3 hours).

“When we looked specifically at the duration of sunshine around the time the eggs were collected, we saw a similar increase to that seen for egg collection during the summer,” Dr Leathersich said.

“The live-birth rate following a frozen embryo transfer from an egg that was collected on a day with fewer hours of sunshine was 25.8%. This increased to 30.4% when the embryo came from an egg that was collected on days with the most hours of sunshine.

“When we considered the season and conditions on the day of the embryo transfer, this improvement was still seen.”

The temperature on the day of egg collection did not affect the chances of a live birth. However, the chances decreased by 18% when the embryos were transferred on the hottest days (average temperature of 14.5-27.80 C) compared to the coolest days (0.1-9.80 C), and there was a small increase in miscarriage rates, from 5.5% to 7.6%.

“There are many factors that influence fertility treatment success, age being among the most important. However, this study adds further weight to the importance of environmental factors and their influence on egg quality and embryonic development,” Dr Leathersich explained.

“Optimising factors such as avoiding smoking, alcohol and other toxins and maintaining healthy activity levels and weight should be paramount. However, clinicians and patients could also consider external factors such as environmental conditions.”

Oner factor that may play a role in the increased live birth rates after egg collection in the summer and during more sunshine hours include melatonin, with levels of this hormone usually higher in winter and spring when the eggs released in summer are still developing in the ovaries.

Differences in lifestyles between winter and summer months may also play a role.

“Finally, given the huge increase in so-called “social egg freezing” for fertility preservation and the fact that this group generally have flexibility about when they choose to undergo treatment, it would be very interesting to see if these observations hold true with frozen eggs that are thawed and fertilised years later,” Dr Lethersich concluded.

“Any improved outcomes in this group could have big impacts for women making decisions about their future fertility, but the long-term follow-up required means it is likely to be some time before we can draw any conclusions for this population.”