Eric Martin explores how WA’s clinical trials are run and what impact the COVID pandemic has had on drug and treatment development.

Eric Martin explores how WA’s clinical trials are run and what impact the COVID pandemic has had on drug and treatment development.

While new medicines and treatments are extensively tested in laboratories and in animal studies, to understand how a new drug works in humans it needs to be tested in vitro in a clinical trial.

Clinical trials demonstrate the drug’s safety and efficacy and optimal dosages, the results from which can lead to the development of treatments that can prevent thousands of deaths each year and improve the lives of the many people who suffer from various medical conditions.

Australia currently enjoys a strong international reputation as a destination of choice for clinical trials: in 2019, there were 1,820 ongoing trials in Australia which contributed an estimated $1.1 billion a year to the economy and the industry continues to grow.

Linear, a not-for-profit organisation owned by the Harry Perkins Institute, is a leader in the field, with more than 20,000 clinical trial participants.

Medical Forum spoke with Dr Lara Hatchuel, its associate medical director, about the significance of Australian clinical trials and what impact COVID has had on their operation.

“It does seem slightly unassuming, but there’s a lot of benefits to bringing trials to Australia: our diverse population and the fact that we can get slightly more streamlined regulatory approval than in the United States. These are drawcards to coming and doing research in Australia,” Dr Hatchuel said.

However, as Linear’s target market has traditionally included backpackers and international students keen to earn some extra cash to fund their time in Australia, COVID has had a significant impact.

“The COVID pandemic has certainly posed a challenge. The travel restrictions have affected volunteer recruitment because we rely on volunteers from across the world, as well as the eastern states,” she said.

Missing backpackers

“Travellers would usually have their first stop in Perth, contribute to research, do a fantastic trial and be paid for it, which would fund the rest of their travelling experience. Since the borders have been closed, we have seen saw a decline in interest.

“Travellers would usually have their first stop in Perth, contribute to research, do a fantastic trial and be paid for it, which would fund the rest of their travelling experience. Since the borders have been closed, we have seen saw a decline in interest.

Another COVID-related challenge has been the need for people to isolate because they have either contracted the virus or been deemed a close contact.

“We’re just starting to feel the effects of it now, whereas globally, I can imagine this has been an ongoing problem,” Dr Hatchuel said.

“Yet because clinical trials are so vital to developing safer, more effective drugs, we are still deemed an essential service and we have never halted operations, which is something we’re quite proud of.

“We have really robust COVID policies to safeguard our unit, to protect our staff, and to protect our patients. We have a vulnerable group of people in our unit, which are our oncology patients, and we have taken some great steps to keep COVID out of our unit, and we’ve been successful to date.”

There has also been a silver lining to the pandemic, with interest in clinical trials increasing alongside social commentary on the approval and rollout of mRNA COVID vaccines such as Pfizer’s Comirnaty and Moderna’s Spikevax.

“On the back of COVID-19 there is a greater awareness of the importance of conducting rapid, high quality clinical trials so that we can develop these breakthroughs for treating patients,” Dr Hatchuel said.

“We’ve certainly noticed that people are genuinely interested in contributing towards medical research. People apply for many different reasons, but there is a genuine interest now to help contribute to research, this altruistic wish to be a part of this cause.”

For common good

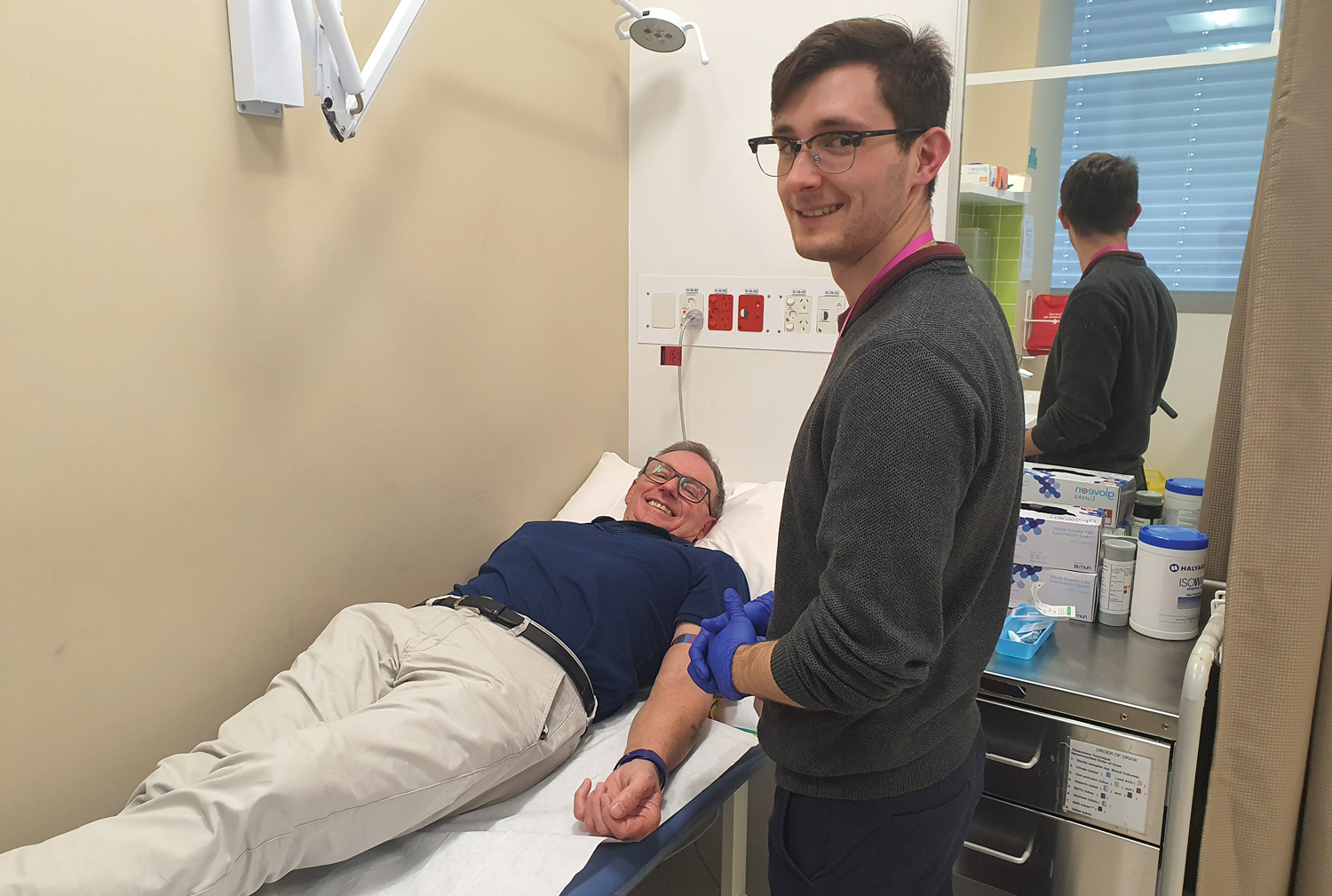

Timothy Roberts, a healthy, semi-retired business owner from Secret Harbour, south of Perth, participated in Linear’s COVID clinical trials early in 2020. He said it was from a genuine concern for his family, after seeing the initial impact of the pandemic unfolding worldwide, that motivated him to volunteer.

“I’d had no experience with medical trials whatsoever except that I knew they went on,” Mr Roberts said. “We’ve got three boys and they’re all in the early stages of their career working in different fields. And I’ve got an 86-year-old dad who’s really the world’s oldest teenager – he and my stepmum were about to hop on a cruise.

“At the time, we were getting those horrible scenes out of Italy of people in intensive care, so we encouraged him to cancel the cruise, like many, many people did around the world, and then we all went into lockdown.

“For the first time in my life I felt absolutely helpless in terms of anything I could do to make a difference.

“I saw the trials on the news, and I thought, that’s something I can actually do because up until then, the only thing I could do to contribute was to stay out of other people’s way and wash my hands.”

Mr Roberts said that he was surprised by the anti-vaccine sentiments that were beginning to surface within the community, which were largely unheard of before the pandemic.

“Prior to COVID, many people wouldn’t think twice about getting a vaccine: just 12 months before that my wife and I had been overseas on a holiday in Africa and we had to take a cocktail of vaccines to get there, and we had to have the equivalent of a vaccine passport,” Mr Roberts said.

“And we didn’t think twice about that.”

Mr Roberts was also unperturbed by the prospect of volunteering for a clinical trial at Linear.

“I’m a big fan of the scientific methodology and to take an experimental vaccine that’s going through that scientific process, to me it was really low risk,” he said.

“And it was something that I could do, which I felt added value to the fight to get us all back out there doing life.”

Not just COVID

While COVID has been a motivating factor for many, there are some who want to be involved for other reasons.

“We might be trialling a drug for a particular form of meningitis, or Alzheimer’s, or heart disease and a volunteer might have had someone affected by that disease – that’s certainly a motivating factor for them to put their hands up to volunteer,” Dr Hatchuel said.

“Of course, we get some students, travellers and medical students that are just interested in contributing to science. And, importantly, these volunteers, which we value so much, are compensated for their time while volunteering.”

Linear’s website lists payments of:

- Approximately $1,500 – $3,000 for 3-6 days in-clinic stay with follow-up appointments

- Approximately $2,500 – $5,000 for 6-11 days in-clinic stay with follow-up appointments, and

- Approximately $5,000 – $8,500 for 11+ days in-clinic stay with follow-up appointments.

Free food and free Netflix and wi-fi are the icing on the cake.

The other cohort of volunteers are those who have a disease or condition that has not responded to existing, conventional treatments in the hope that by participating in a clinical trial they may be part of finding a solution, with a chance of being healed in the process.

“That’s something that we’re trying to really enhance. It frustrates us that an oncology patient who has exhausted all conventional therapy just doesn’t always have access to these lifesaving trials,” Dr Hatchuel said.

Cancer trials

“One of our key missions is to effectively link a rare cancer to a trial, so we’d really love physicians to know about the work we do so that the minute they think cancer, they can immediately think, ‘what clinical trial can I put them on?’

“One of our key missions is to effectively link a rare cancer to a trial, so we’d really love physicians to know about the work we do so that the minute they think cancer, they can immediately think, ‘what clinical trial can I put them on?’

“That really is the forefront of medicine, where you’re at the cutting-edge and you actually have a good chance of curing something and that’s what we’re all about.”

Due to the wide variety of trials taking place, they can involve people of all ages, from children to the elderly, and with all types and stages of a disease or condition.

While most clinical studies need participants who have the disease or condition that a new intervention targets, healthy volunteers such as Mr Roberts also play a role in supporting the discovery of new treatments and interventions, particularly in early-stage trials.

If someone who is ill is given a medication and then gets better, it could be due to a natural recovery or to other factors. To determine if the intervention has worked, the data needs to be compared to a meaningful benchmark. Hence the concept of the active group and the control group.

All clinical trials have guidelines called inclusion and exclusion criteria that must be met in order to allow someone to take part –both aim to ensure that the trial will produce safe, useful and reliable results.

Before participants join a trial, they also need to have tests that allow researchers to evaluate the person’s health before starting the trial treatment, so that at the end of the trial, they can tell if there has been an improvement.

More tests are administered during the trial to monitor participants’ health and see whether the treatment is working.

Checks & balances

Checks & balances

Clinical trials must conform to the Ethical Principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, international Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and in Australia, clinical trials need approval by a Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) registered with the Australian Government’s National Health and Medical Research Council and must follow the guidelines set by the Therapeutic Goods Administration and Medicines Australia.

HREC is guided by The National Statement, the Australian ethical standard against which all research involving humans is reviewed, which was developed jointly by the NHMRC together with the Australian Research Council and Universities Australia, in accordance with the National Health and Medical Research Council Act 1992.

In addition, the NHMRC, together with the ARC and Universities Australia, has issued the Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research to guide institutions and researchers in responsible research practices and ensure that their work has integrity and aligns with community expectations.

As part of the process of informed consent, anyone taking part in a trial must be fully informed about the objectives of the research, what is expected of them, and any risks and potential inconveniences that may be experienced – both during and after the trial.