Outrage over rogue cosmetic surgery practices has triggered not only a probe into the multimillion-dollar industry – it has renewed calls to tighten which doctors can call themselves surgeons.

Outrage over rogue cosmetic surgery practices has triggered not only a probe into the multimillion-dollar industry – it has renewed calls to tighten which doctors can call themselves surgeons.

When an Australian television program aired videos last year of medical staff dancing as they performed liposuction on unsuspecting patients, many people were rightly horrified. But perhaps more worrying, for some doctors it did not come as any great surprise.

Cosmetic surgery is big business, with an estimated half a million Australians spending $1 billion a year on it – more per capita than in the US.

But there have long been concerns within the medical profession about some outliers carrying out questionable surgical procedures, seemingly in plain sight but never challenged.

It took a couple of whistle blower nurses and social media analysts to lift the lid off practices at celebrity cosmetic surgeon Dr Daniel Lanzer’s clinics, which at the time operated in several cities, including Perth.

Dr Lanzer trained as a specialist dermatologist but had worked as a cosmetic surgeon for many years. He built a huge profile thanks to media appearances, TV shows and millions of followers on TikTok and Instagram.

But Cosmetic Cowboys, a joint investigation by ABC Four Corners and several newspapers, revealed an astonishingly cavalier attitude towards surgical procedures at his clinics, with doctors and other medical staff seemingly more intent on entertaining a social media audience than delivering safe care to patients, some of whom were under general anaesthetic.

A young woman was seen with an arm across her bare breasts while being asked by two male staff how much fat she thought they would be able to suck out of her abdomen during liposuction.

Pictures taken inside the clinics showed human fat stored in kitchen fridges, syringes sitting alongside water bottles, and surgical instruments stored in a suitcase.

Perth plastic surgeon and AMA WA president Dr Mark Duncan-Smith described it as “spine-chilling”.

“It was atrocious, it gave me goose-bumps when I saw it – it was just awful,” he told Medical Forum.

WA specialist plastic surgeon Dr Brigid Corrigan, a member of the Australian Society of Plastic Surgeons, agreed there was no way to sugar-coat practices that appeared both unprofessional and unsafe.

“If you’ve undergone a surgical training program, you understand the basic principles of sterility,” she said. “And when I saw that program, I thought, ‘Oh my god’. It might have been selective in the way it was edited, but if you watched that, anyone would be rightly horrified by what they saw.”

Soon after the damning program aired, Dr Lanzer surrendered his registration and retired, while the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency and the Medical Board ordered a review of patient safety issues in the cosmetic surgery sector.

The review is now underway, being led by former Queensland Health Ombudsman Andrew Brown, who is due to hand down a report by the middle of the year.

Areas to be examined include better ways to protect patients, the unfettered use of social media by some cosmetic surgeons to promote their services and why medical practitioners and clinicians are not fulfilling their mandatory requirements to report wrongdoings.

AHPRA chief executive Martin Fletcher conceded the inquiry was triggered by the media exposure.

“Obviously we were very concerned by the material that was broadcast … and although some of that was known to us and were matters we were actively investigating, there was an awful lot of information we didn’t know,” he said at the time.

“Patients have a presumption that the health care system is safe, and because it’s regulated by the government and they know doctors need to have licences, patients go along and think everything is going to be safe and hunky dory. ”

Debate rages

The fallout from the program has seen the many vested interests and professional organisations arguing their case – and claims of turf war tactics.

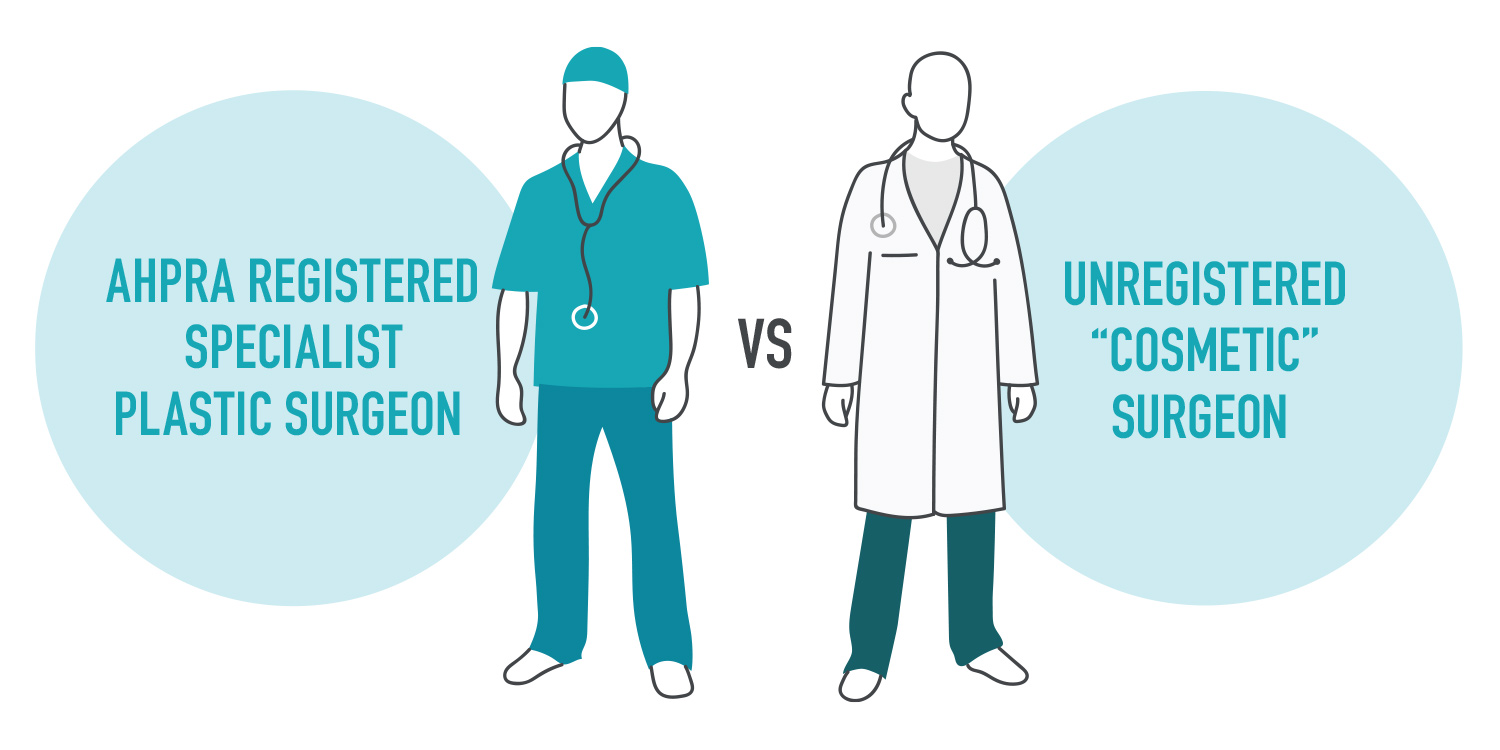

The Australasian Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons said that only doctors who had successfully completed Australian Medical Council-accredited training could use legitimate, approved specialist surgical titles. But most practitioners who used the title ‘cosmetic surgeon’ were not registered surgical specialists and had not completed AMC accredited training.

ASAPS president Dr Robert Sheen told Medical Forum the whole system of a presumption of safety and public trust was being jeopardised.

“It’s not the fault of the media program because what they’re doing is exposing things that people need to know, but it damages people’s confidence in the system itself, and that’s across the board not just in cosmetic surgery; everyone gets tarred with the same brush,” he said.

“Patients have a presumption that the health care system is safe, and because it’s regulated by the government and they know doctors need to have licences, patients go along and think everything is going to be safe and hunky dory.

“If someone calls themselves a cosmetic surgeon, then the patient makes a bunch of assumptions that these people are highly qualified specialists in cosmetic surgery.

“While some practitioners are very well qualified, some are not, but patients don’t understand the difference and can have poor outcomes as a consequence, and that’s very problematic.”

Dr Sheen said circumstances had changed from the days when there was a small number of specialists, and patients went through their GP, who had some knowledge of the specialists so could act as a type of gatekeeper.

“But what’s happened is that the number of doctors has multiplied, and the advertising – particularly online – has just exploded and because cosmetic surgery doesn’t attract Medicare benefits, patients can self-refer. So, the GP’s gate-keeping role has dropped out in the process.

“We’re not saying that this doctor should or shouldn’t be allowed to do whatever – it’s actually not our role – but we do believe medical practitioners should tell the truth to their patients as part of open disclosure.

“It’s very simple – make doctors say what they are, not what they’re not.”

Dr Sheen said ASAPS believed that the national law needed to be tightened.

“We’ve said to AHPRA we will lobby to get the laws made more explicit so you can do your job,” he said.

“The current status quo doesn’t help AHPRA, it doesn’t help practitioners and it certainly doesn’t help patients. We’re keen to work constructively with AHPRA to facilitate them to be much more proactive looking after patients.”

National register call

National register call

But while the Australasian College of Cosmetic Surgery and Medicine (ACCSM) has welcomed the AHPRA review, it wants a single national register of cosmetic surgeons.

It argues that because the current system allows any doctor to call themselves a cosmetic surgeon, patients cannot easily identify whether a doctor had the necessary specific training to be competent and safe.

The college has also weighed into the turf war argument, claiming Royal Australasian College of Surgeons’ specialist surgeons are trying to secure a monopoly in advertising themselves as surgeons to patients seeking cosmetic surgery, when many of these doctors have little or no training in cosmetic surgery.

It maintains the skills needed for cosmetic surgery are very different from those for reconstructive plastic surgery, because cosmetic surgery is done to change the appearance of healthy tissue, not to reconstruct after disease or injury.

And it says only a minority of specialist surgeons obtain formal cosmetic surgical training either overseas or by completing the ACCSM’s postgraduate training program and examinations.

Dr Duncan-Smith rejected claims it was a turf war between plastic surgeons and cosmetic surgeons.

He said “fringe activity” by some doctors was bad for the whole profession and AHPRA “had a lot of egg on its face” over the recent bad media.

“They were embarrassed at a bureaucratic level by that program Cosmetic Cowboys, but it’s actually nothing to do with a turf war, it’s about patients having a reasonable expectation that when they see someone calling themselves a surgeon, that person has recognised training.

“What we saw last year is terrible, and we’ve seen other clowns doing liposuction from back offices, so it’s not about what doctors want to call themselves, it’s about safety.

“It’s an interesting phenomenon when someone who’s not really trained as a surgeon all of a sudden thinks they are somehow religiously gifted in this area.”

The bigger picture

And there is a lot more at stake than issues within the cosmetic surgery industry.

AHPRA’s inquiry has an obvious bedfellow – the ongoing review into the use of the term ‘surgeon’ which has been languishing on the backburner for more than three years.

The country’s health ministers have been consulting on reforms to the regulatory scheme governing all health practitioners in Australia since 2018. They supported restrictions to the use of the titles surgeon and cosmetic surgeon, but argued more work was needed.

The Victorian Government is leading that public consultation, which closes next month (April), with health ministers due to consider the matter over the next 12 months.

Options on the table include restricting the title of surgeon under national law; strengthening the existing framework; undertaking major public information campaigns, or maintaining the status quo.

Dr Corrigan said it was the title surgeon that was most confusing to patients.

“It comes back to the crux of the issue – what you need to call yourself a surgeon,” she said.

“While cosmetic surgery is the one that gets the attention, it goes back to the basic issue that someone shouldn’t be calling themselves a surgeon if they haven’t had specialist training.

“But a lot of practitioners will have glossy magazines, brochures and websites and come across as quite experienced and well-trained, so it becomes hard for even medical practitioners to know.”

The real deal

Dr Duncan-Smith said the fundamental question the public wanted to know was if were they dealing with a real surgeon or not.

“And that’s where the term ‘surgeon’ from the point of view of a doctor, really should be reserved for someone who has a FRACS or equivalent.

“You can’t protect the term surgeon altogether, because you can have an arborist or tree surgeon, and dental surgeons, but there has to be a greater good we’re trying to achieve.

“You do have dermatologists who have training in Mohs surgery (for skin cancer), but just as equally it could be called Mohs skin cancer treatment.

“Because if the word surgeon is associated with a medical doctor, the public has the right to expect that the doctor has a FRACS or equivalent.

“Now if a doctor who has no formal surgical training wants to do tummy tucks, or breast augmentation or liposuction, then they should do that without misleading the general public by using the word surgeon.”

More than skin-deep

But the Australasian College of Dermatologists (ACD) told Medical Forum there was already public confusion over the types of practitioners working in the skin cancer space.

“Using terms like ‘skin cancer doctor’ only adds to the confusion, because in Australia anyone with a basic medical degree is able to call themselves a skin cancer doctor or similar,” it said.

Surgical techniques were an essential part of specialist dermatology practice, and the development of skin surgery skills and expertise comprised a significant proportion of the four-year AMC-accredited ACD specialist training program.

“Some specialist dermatologists have further focused their scope of practice to Mohs micrographic surgery by completing further ACD-accredited training. ACD maintains a register of specialist dermatologists who practise Mohs surgery, and they are required to complete ongoing medical education and quality assurance program activities.”

Dr Corrigan said concerns raised about practices at Dr Lanzer’s clinics only highlighted that being a surgeon was not just about techniques.

“In any surgical procedures there can be complications, and one of the things I’ve found troubling is that it’s not just about doing a course or being trained in a particular cosmetic surgery technique.

“If you’ve done surgical training, you have that background in core foundation skills in surgery, which are things like sterile techniques or managing bleeding or infections in sick patients.

“So, while in my practice I perform breast implants, if I have a problem and there’s a bleeding patient or someone with a catastrophic infection, I’m falling back on skills I learnt well before I learnt to put in breast implants.”