A placental examination was found to be an accurate pathologic determination of more than 90% of previously unexplained pregnancy losses, according to new findings reported on 19th September in the Reproductive Sciences.

According to Red Nose Australia, every year, “around 110,000 Australians have a miscarriage, 2,200 more endure the pain of stillbirth, 600 lose their baby in the first 28 days after birth and many more face the grief of termination for medical reasons.”

Miscarriage rates reveal that the cumulative risk of pregnancy loss between 5 and 20 ranges between 11 and 22%, and although pregnancy loss rates decrease after 20 weeks of gestation, there are still approximately 2 million stillbirths globally per year.

Current pregnancy loss classification systems require improved consistency to determine the potential causes of each pregnancy loss more accurately with a 2009 systemic review revealing large variability in the rates of unexplained stillbirths, ranging from 9.5 to 50.4%.

Consistent with these findings, the US CDC’s 2015–2017 Cause of Foetal Death report found that the most frequent cause for foetal death was “Unspecified.”

Senior author Dr Harvey Kliman, director of the Reproductive and Placental Research Unit at Yale School of Medicine, explained that patients who suffer such pregnancy outcomes were often told that their loss was unexplained and that they should simply try again – contributing to patients’ feeling of responsibility for the loss.

“To have a pregnancy loss is a tragedy. To be told there is no explanation adds tremendous pain for these loss families, and our goal was to expand the current classification systems,” he said.

“Placental abnormalities are commonly detected in adverse pregnancy outcomes and have been associated with potentially preventable types of losses – one systemic review reported that up to 65% of stillbirths are attributable to placental abnormalities.

“However, absent in these abovementioned classification systems are the categories of dysmorphic chorionic villi, represented by trophoblast inclusions, and the consistent inclusion of the category of a small placenta, which is clearly associated with pregnancy loss.

“We thus hypothesized that expanding the placental pathology diagnostic categories to include the two explicit categories of dysmorphic chorionic villi and small placenta in examining previously unexplained losses could decrease the number of cases that remained ‘Unspecified.’”

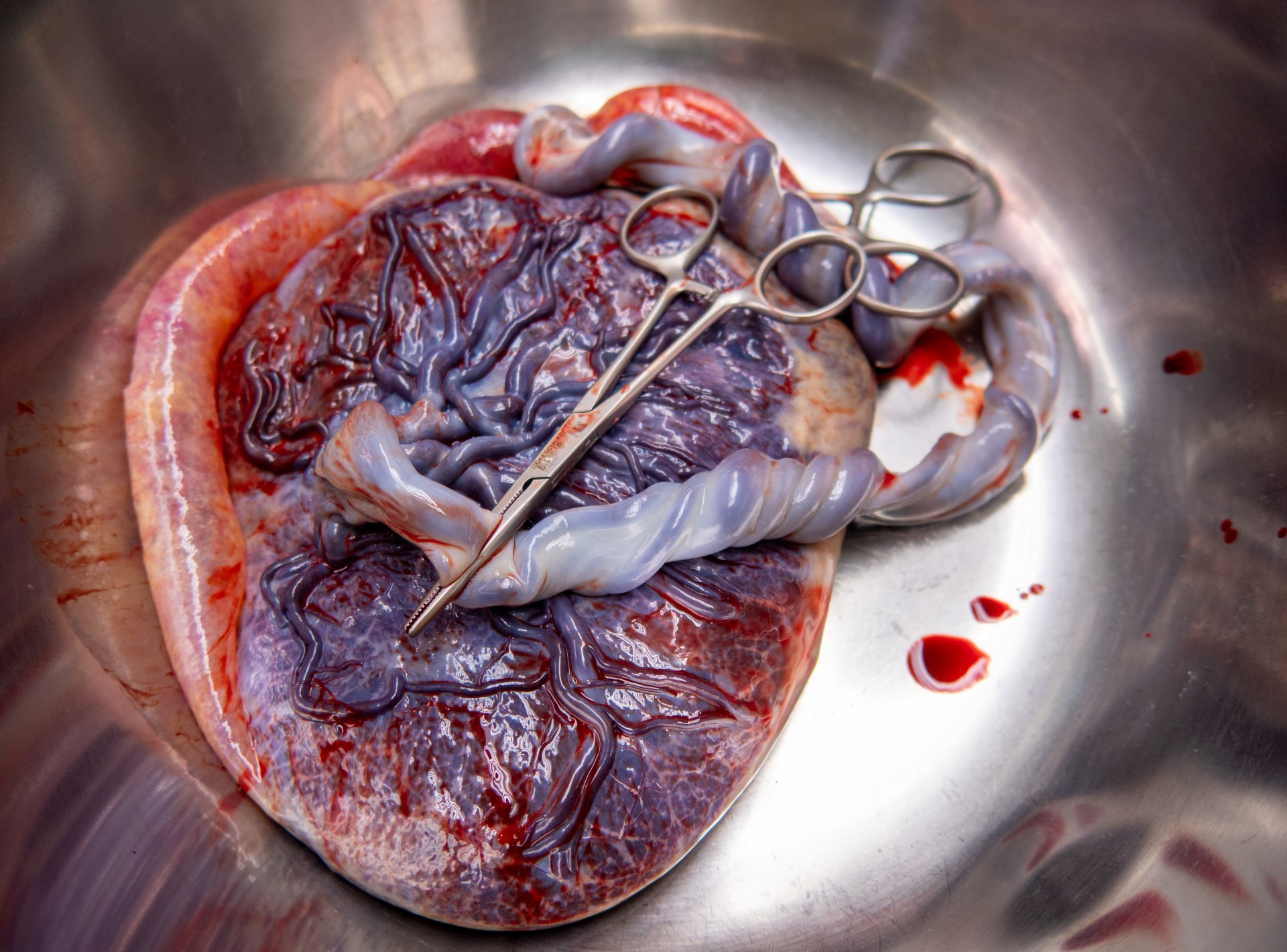

The team started with a series of 1,527 single-child pregnancies that ended in a loss that were sent to Yale for evaluation. After excluding cases without adequate material for examination, 1,256 placentas from 922 patients were examined and of these, 70% were miscarriages and 30% were stillbirths.

By adding the explicit categories of ‘placenta with abnormal development’ (dysmorphic placentas) and ‘small placenta’ (a placenta less than the 10th percentile for gestational age) to the existing categories of cord accident, abruption, thrombotic, and infection, the authors were able to determine the pathologic diagnoses for 91.6% of the pregnancies, including 88.5% of the miscarriages and 98.7% of the stillbirths.

Abnormalities were identified in 373/378 (98.7%) of analysed stillbirths.

The most common pathologic feature observed in unexplained miscarriages were dysmorphic placentas (86.2%), a marker associated with genetic abnormalities and the most common pathologic features observed in unexplained stillbirths was a small placenta (33.9%), dysmorphic chorionic villi (116, 30.7%), and cord accidents (57, 15.1%).

Of the 873 total cases of losses with dysmorphic chorionic villi, 644 (73.8%) cases showed TIs, while 229 (26.2%) showed trophoblast invaginations only.

“This work suggests that the small placentas associated with stillbirths could have been detected in utero — flagging those pregnancies as high risk prior to the loss. Likewise, the identification of dysmorphic placentas may be one way to potentially identify genetic abnormalities,” Dr Kilman said.

Adding these two diagnostic categories appears to have eliminated most remaining unexplained loss cases, supporting their adoption and inclusion in pregnancy loss evaluations.

“Having a concrete explanation for a pregnancy loss helps the family understand that their loss was not their fault, allows them to start the healing process, and, when possible, prevent similar losses — especially stillbirths — from occurring in the future.”