Western Australia has, so far, been successful in controlling COVID-19 cases, largely due to West Australians’ compliance with public health measures, the state’s relative isolation, lack of population density and the vital role of contact tracing.

Western Australia has, so far, been successful in controlling COVID-19 cases, largely due to West Australians’ compliance with public health measures, the state’s relative isolation, lack of population density and the vital role of contact tracing.

Victoria is another story. Behind the headlines, politicians and health bureaucrats are finely tuned teams of investigators meticulously tracing each contact of a confirmed COVID-19 case.

Contact tracing may have become part of the vernacular in these COVID-19 times, however, it has been part of public health practice for centuries, with the first recorded contact tracing being performed by physician Andrea Gratiolo in 1576 to trace the contacts of a symptomless woman accused of spreading the bubonic plague in northern Italy.

Gratiolo meticulously investigated the woman’s movements and interviewed people she had been in close contact with and found none was infected with the black death.

Although Gratiolo’s contact tracing may seem like the rational thing to do, at the time it was unheard of, particularly when consensus of the plague’s causality was thought to be God’s punishment for sinners.

From Gratiolo’s nascent efforts, contact tracing has become an essential practice in investigating the transmission of infectious diseases. While technology and infectious disease epidemiology has made contact tracing more effective and efficient, the practicalities are much the same as they were four centuries ago – it comes down to a conversation between two people.

What is contact tracing?

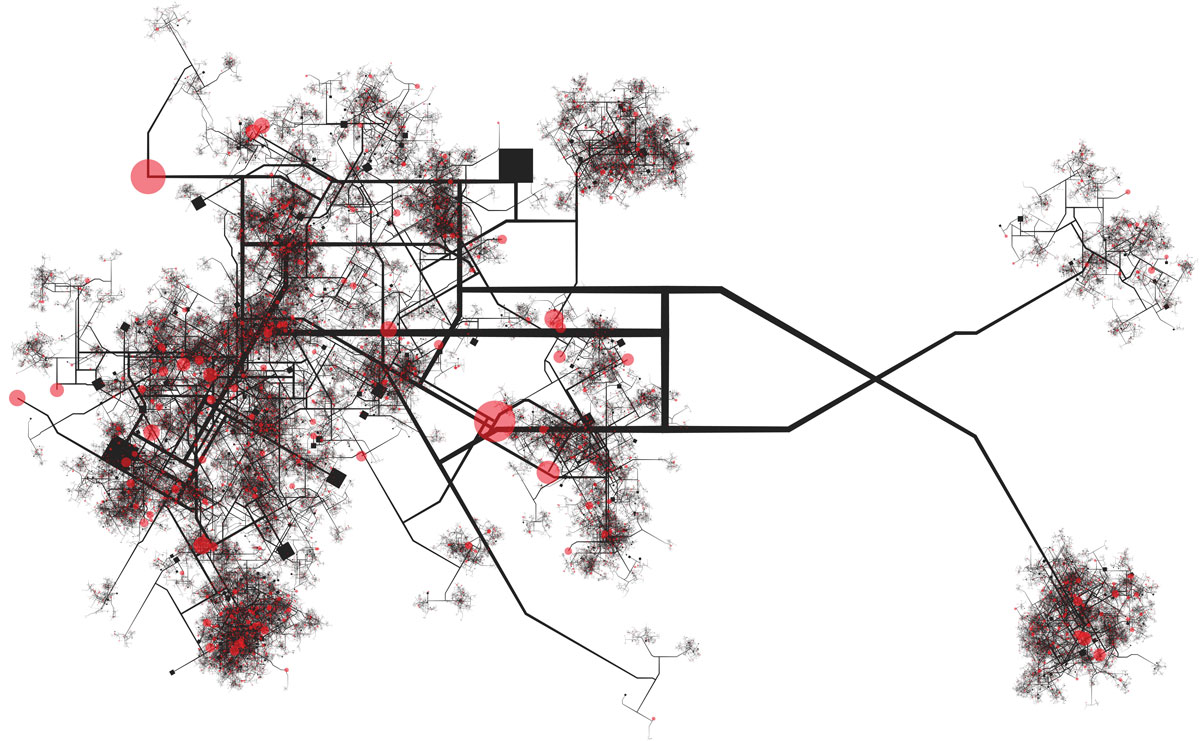

In essence, contact tracing is investigative work seeking the source or index case of an outbreak and methodically identifying all possible contacts of a positive case, interviewing them and ascertaining, in granular detail, their interactions, then contacting and assessing each possible contact and, depending on their infection risk, having them placed in quarantine.

To understand how the process works in WA, Medical Forum spoke with the Clinical Lead of Public Health Operations for COVID-19 at the WA Department of Health, Dr Ben Scalley.

Every time a positive case of COVID-19 is identified, the contact tracing team at WA DoH is notified and the process of contact tracing begins.

While COVID-19 has presented contact tracers with a novel disease to trace, the fundamental processes of tracking cases and contacts is the same as used elsewhere in public health system and was used during last year’s measles outbreak.

According to Dr Scalley, once a case of COVID-19 is confirmed, the team looks at the movements of each case in detail and the people with whom they have been in contact. These contacts may be obvious – same household, workplace and social network – to the less obvious such as those from the use of shared facilities including bathrooms.

“When a close contact is established, they are notified and put into quarantine for 14 days from the time of their exposure. We then monitor them for symptoms so that if they become unwell, they are isolated at home, stopping the chain of transmission,” he said.

The radical change for the tracing team during COVID-19 is its size. From a core team of 25 it has increased to 170 at the peak of the pandemic. The team is primarily nurses and doctors who have received specialised training.

The radical change for the tracing team during COVID-19 is its size. From a core team of 25 it has increased to 170 at the peak of the pandemic. The team is primarily nurses and doctors who have received specialised training.

Elements of the team are currently helping the Department of Health and Human Services in Victoria to contact trace during its coronavirus outbreak.

Dr Scalley attributes success in flattening the curve here in WA to the population taking the disease seriously, which has made his team’s work all the easier.

“The good thing is that people within the state have taken to the social distancing measures. People have taken quarantine seriously when they return from overseas, they have removed themselves and self-isolated if they have not been feeling well, or when they were found to be a close contact of a confirmed case.

“All these measures have meant that contact tracing in WA has been a lot easier.”

Dr Sculley said each investigation, typically, can take days, especially if people were unaware they were infectious or did not quarantine.

“Often the conversation initially might be up to two hours longer and might require clarifications. If someone asked you what your exact movements were a week ago, it might take a little while to recall. And then talking to all the different contacts, that might take a number of hours,” he said.

“There’s a lot of skill in prompting people with the right questions, such as asking them to look through their financial records to confirm where they may have been.

“Then we’re checking in on the confirmed cases every day until they are no longer infectious and all of the quarantined contacts for 14 days. There’s a lot of work that goes into each of the cases we’ve had so far.”

Dr Scalley said the confirmed cases were often easier calls to make as they have already been tested and have assimilated their new normal. Whereas the contacts of confirmed cases are usually unaware they have been in close contact with someone who was infectious.

“That is quite a hard conversation to have, telling someone to essentially take a break from their life for 14 days and stay home.

“The vast majority of people we speak with are accepting because they understand the broader context, the broader benefit to all West Australians.”

The contact tracers

Understanding the history of contact tracing and the processes are all well and good, yet who are the people undertaking this vital work?

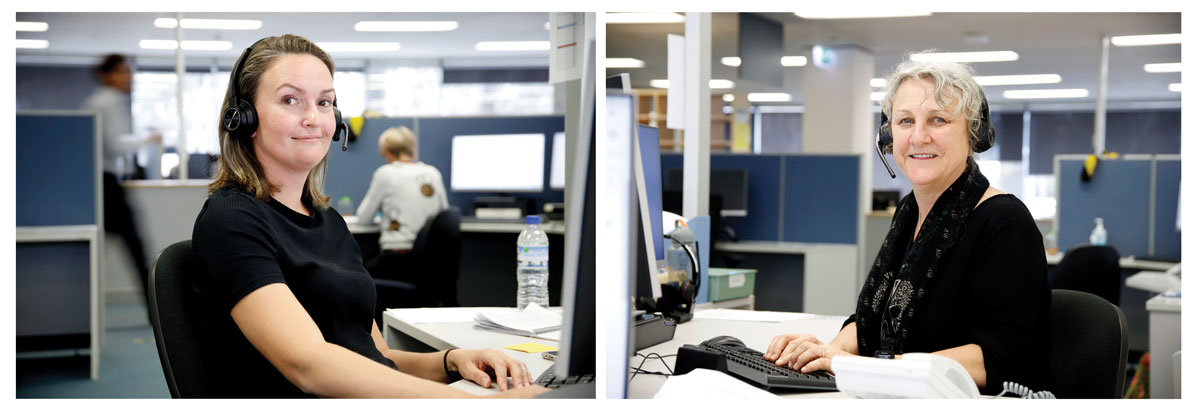

Clinical nurses Honey Lawton and Jane Newcomb are part of WA Public Health Operations’ (WA PHO) contact tracing team currently assisting Victoria Health.

Prior to becoming a contact tracer, Mrs Lawton told Medical Forum she worked as a clinical nurse in a tertiary hospital for 15 years where she recognised the importance of public health in disease prevention. When the opportunity was presented to become a contact tracer, she jumped at it.

Mrs Newcomb was a clinical nurse at the Australian Council of Healthcare Standards – travelling around Australia assessing mandatory standards. When she was asked to assist, she thought it was an opportunity to do her bit to help out in a pandemic.

Most of the contact tracers in the WA PHO are registered nurses, yet, according to Mrs Newcomb, the role not only requires clinical skills, education, and experience but also effective communication and investigative skills.

“It helps to be able to pick up clues over the phone, including being able identify any problems or concerns as we’re talking to people. We need to have good problem-solving skills and be something of a historian to trace people’s movements in their incubation and infectious period.”

The WA PHO has four working teams – WA contact tracing, ongoing management (of WA cases and close contacts), quarantine management and Victoria contact tracing.

“Staff will then rotate within these teams to allow everyone to remain efficient and up-to-date on new processes within each area. No two cases are alike – and each case is interviewed individually,” Mrs Lawton said.

A day in the life of a contact tracer can vary depending on the amount of cases or new cases, Mrs Newcomb said.

“If you are interviewing a newly confirmed case, you’re identifying their movements and any close contacts who could potentially put the community at risk. These people then need to be contacted and informed of the need to isolate for 14 days, preferably away from others in their household so as not to put them at risk.

“Each case is followed up individually, although sometimes with family members in the one household, one key person (such as mum or dad) will provide the information for the family.”

When a person has been identified as a close contact with a confirmed case, contact tracers are often the first to inform them, which can be challenging, said Mrs Lawton.

“They usually handle it well, although for some people being asked to quarantine for 14 days can cause them some stress, as this can obviously have an impact on their ability to earn an income.”

Mrs Newcomb underscores why effective communication skills are so important for contact tracers: “Informing someone of their contact with a case and what it means for them regarding quarantine can be stressful, so compassion, understanding and empathy is important, as well as being informative about what quarantine means to the person and their family.”

According to the Department of Health, all of WA’s recent COVID-19 cases have occurred in people who have come from overseas and have been required to quarantine in a hotel upon arrival. Therefore, their close contacts have been minimal and easily traced.

“Only a small portion of our case load is focused on active COVID-19 cases as we have low numbers In WA at present. We are in contact with our active cases daily to monitor their health and symptoms,” Mrs Lawton said.

Although WA’s only cases are currently from overseas, Victoria has significant numbers of new cases from community transmission. The WA PHO team has been tasked with assisting the contact tracing effort currently under way by the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and Australian Defence Forces.

“We are given roughly 20 to 30 cases daily via a live database that lists relevant contact information. With this information we then contact trace positive cases and close contacts, at the end of each day a progress report and any issues with follow-up is provided back to Victoria,” Mrs Lawton said.

Mrs Newcomb offers some insight into the situation in Victoria:

“I have been the team lead for Victorian cases and developed a rapport with some of the team leads there. I phone them first thing in the morning our time to see if there have been any changes in direction or processes that we needed to be aware of.

“We then check cases allocated to us and look at our capacity to do above that. I believe that WA has collaborated with Victoria to help as much as we can.”

Back in 1576, Andrea Gratiolo had no methodology or process, this is not the case today.

“Each contact tracer follows the current operating procedures which guide us on what information we need. However, the actual interview itself can become quite a personalised process. It is important to establish a good rapport with the client as it will shape all future interactions with them,” explained Mrs Lawton.

However, with the rapidly expanding body of knowledge surrounding COVID-19, the WA PHO must be agile as processes can change often.

“We have developed set processes for contact tracing, however, with COVID-19, specific regulations for people coming to WA around testing and quarantined are changed and updated frequently, so the team must ensure they keep up to date with these changes daily,” said Mrs Newcomb.