Dr Femi Oshin didn’t take a direct route to medicine, but an engineering degree has certainly helped the vascular surgeon in his area of passion – diabetic foot disease in rural and remote communities.

Dr Femi Oshin didn’t take a direct route to medicine, but an engineering degree has certainly helped the vascular surgeon in his area of passion – diabetic foot disease in rural and remote communities.

By Ara Jansen

In Nigeria, doctors, engineers and teachers are prized professions. In Dr Femi Oshin, his family got all three.

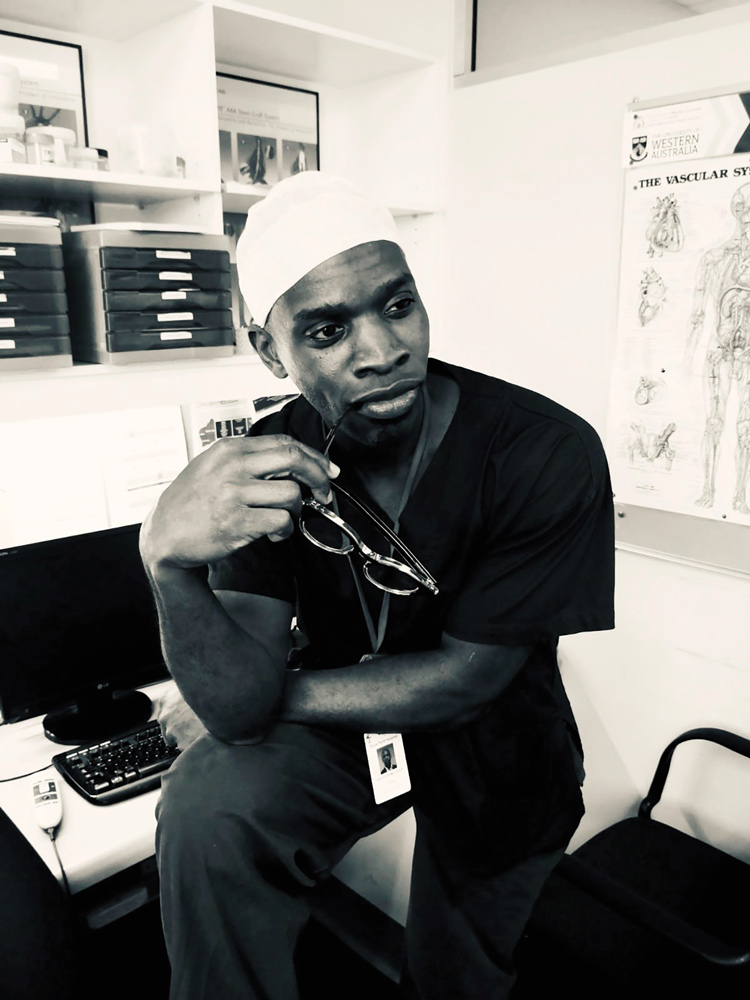

Femi is a vascular surgeon and medical co-director of the Hospital Logistics and Acute Access Division at Royal Perth Hospital as well as being a transplant to Perth. Femi – or Olufemi to his mum – holds degrees in both engineering and medicine. The former it turns out has been hugely helpful for a doctor.

Femi is a vascular surgeon and medical co-director of the Hospital Logistics and Acute Access Division at Royal Perth Hospital as well as being a transplant to Perth. Femi – or Olufemi to his mum – holds degrees in both engineering and medicine. The former it turns out has been hugely helpful for a doctor.

An excellent high school student, but when it came down to the final exams, 17-year-old Femi didn’t perform as well as he’d hoped. He’d been provisionally accepted into several medical schools but his exam results didn’t stack up. Instead, he went into engineering at the University of Liverpool, focusing on tissue engineering and material science.

The work was interesting. He investigated all sorts of cutting-edge ideas such as regenerating or replacing body parts such as lenses in the eye, and hip and knee joints. There were lots of lessons from the aerospace industry to create advanced materials and in some instances, this was coupled with cell technology to create biomaterials that restore or augment biological tissue function.

“It was fascinating,” says Femi. “And closely aligned to medicine. Turns out, a lot of the things I did have been very applicable to what I am doing now. We’ve been using engineering solutions on some of the problems we have in vascular surgery.

“I have been involved in research looking at people who have lost body parts through diabetes, and what materials we can use to regenerate lost tissue. I work with some extremely talented engineers and they love that we can talk the same language.”

Femi completed his engineering degree and obtained his medical degree in 1999. Partway through his postgraduate medical training, he took two years out to focus on research and was awarded his doctorate. He completed vascular training in his late-30s after 10 years in the surgical training program in the United Kingdom.

Much travelled

Born in Ethiopia to Nigerian parents, Femi’s father worked for the Nigerian foreign service. The family moved around a lot and his youngest brother was born in France. When Femi was six, the family moved to the UK. A British education was highly prized, so the family settled in London for the children’s education.

Born in Ethiopia to Nigerian parents, Femi’s father worked for the Nigerian foreign service. The family moved around a lot and his youngest brother was born in France. When Femi was six, the family moved to the UK. A British education was highly prized, so the family settled in London for the children’s education.

“I always had an interest in medicine and wanted to help people, particularly through surgery as I like doing things with my hands and being precise. I remember when we were growing up, my dad drew a picture of the human body and the digestive system, and I was totally fascinated. I always had that curiosity, things like that were easy to understand and medicine seemed like a natural progression.

“There was never any other path for me. Even when I didn’t get in at first, I always knew I was going to get there. As an immigrant, the desire and drive to succeed is palpable.”

In 2017, Femi found his way to Perth as part of a fellowship and at the urging of a friend – a vet – who lives here and loves it. Within a few days of arriving, Femi declared the place was a lot better than he thought it would be and perhaps it was a place to settle long term.

It was initially understood as part of the fellowship that Femi would return to the UK, but he gave up his permanent job there to stay in Perth. Six years later Femi has successfully completed the Australian Fellowship exams to have his qualifications recognised and considers this home.

He’s gone through the same set of exams four times to achieve his end goal and is extremely happy to be done with them. Femi credits resilience, hard work and the strong belief he would get through, which kept him going while juggling work, two highly active children, a marriage breakdown and COVID.

“It has been tough, but I still get up and am pleased to go to work and know that I am making a difference. I miss family and friends in the UK, but I have made some incredible friends here who have become family, and have met people who have been incredibly supportive. There’s a lot to be thankful for.”

What has become one of Femi’s biggest interests and professional passions has been delivering equitable health care to Aboriginal people in rural and remote areas. He admits it poses huge challenges on several fronts, including from inside the health system, through to public perception.

Positive outlook

“The ability to have a more sanguine approach to this very complex problem is really important and helps me avoid taking setbacks personally. I understand there are different agendas and potential solutions for this issue. Navigating this to make progress to improve outcomes for Aboriginal people is going to take effort, of course, but I believe we are going to get there.”

And Femi is well placed to be part of that difference, which includes creating the WA Foot Collaborative Annual Meeting in 2019. The three-day conference brought together like-minded health professionals, specialist speakers from all over the world and patient advocacy groups such as Diabetes WA to focus on foot complications because of diabetes.

In an Australian first, the conference also featured a hands-on multidisciplinary cadaveric course to teach core skills in the surgical management of diabetic foot complications.

“I want to continue to push the boundaries in this area of Aboriginal health care and diabetic foot disease. As part of the tireless work with Kimberley Aboriginal Medical Services (KAMS), WACHS and Diabetes WA, we have managed to get a full-time podiatrist based in Broome. That’s been a huge game changer and Broome, in my view, is a regional hub for diabetic foot care in the Kimberley.”

Working with the podiatrist in situ makes it much easier for Femi to decide if someone needs surgery. Patients arrive on Thursday, he operates on a Friday and, where possible, they go home over the weekend.

“These patients are no longer coming to Perth fearful and not knowing what’s going to happen to them. Because they already know me, there’s a bit of a comfort in that. Nothing like word of mouth to spread the word that it might not be as bad as you think and the mob in Perth will look after you. I’m very excited about the ongoing development of the relationship with regional communities.

“There is enough going on that this could be a full-time job for me. One thing we have been exploring and thinking a lot about is how we could deliver this service at other sites. Along with other like-minded people we could make this the norm and part of sustainable change.”

Tech unites

Tech unites

Femi says one of the great lessons of COVID was leveraging technology – the use of telehealth – especially in remote areas and regional centres. His approach to diabetic foot care has embraced this and it has made all the difference in building patient-doctor relationships, which otherwise would never have happened for him in Perth.

“I can still work with patients who can’t come to see me in person, I can work around the times that work for them and build those relationships. We can also fix some problems without them having to come to hospital, rather than them coming to hospital only to find out they didn’t need to come.

“It’s not unusual for patients from remote communities with diabetic foot disease to end up in Perth. But if we can work with someone who knows them, like a podiatrist, then maybe we don’t have to bring them down. Between us, they are still getting the knowledge to help the problem. The more we can leverage local expertise, the more we can provide them with access to specialist knowledge.”

While Femi doesn’t formally teach, he certainly believes in helping others to learn. He’s not a fan of didactic learning because, in his experience, teaching doctors to be great clinicians is only part of the job. Teaching them to be able to reflect on what they do and how they do it is also important. Fostering and encouraging compassion and connection

should be equally prized.

“I also tell junior colleagues there’s always something to learn in the ordinary. I remind people they have taken the Hippocratic Oath for a reason – and it must mean something. Doctors are scholars, teachers and scientists and that is an immense privilege.”

A natural runner, you’ll also find Femi at the gym or chasing after his kids and the dog as his way of keeping in shape. He likes to paint and draw during quieter moments and has a passion for home improvement, which apparently,

he’s quite good at.

Luckily, he also doesn’t like mess and is very ordered, so he tidily finishes the jobs he starts. He finds it therapeutic and is another outlet where he can enjoy using his hands. Largely self-taught, he couldn’t afford to pay a tradesman to do fix-it jobs while he was studying and training. He says the affinity his children have for drawing and building Lego seems to echo their dad’s love for home improvement and working with his hands.

Dab hand

Femi’s mother went to Le Cordon Bleu while they lived in France, so he definitely grew up with a solid basic knowledge of how to cook. In Liverpool, many of his university friends missed their Sunday dinners at home, so Femi took it upon himself to cater for them. They paid for the ingredients, he channelled his mum’s skills and sometimes turned a small profit at the end of the night.

Since moving to Australia, Femi has added improved barbecuing skills to his repertoire. Now all his exams are done, he’s enjoyed finding time to entertain again and teaching his sons the appropriate use of cutlery.

Saturdays at the Oshins are given over to rugby and athletics, the boys are learning to play chess and have discovered board games. There’s also always Lego, crafts and Harry Potter on audio book.

Femi’s partner Kirsty is a social worker. The pair met online and Femi said he was really into wine – accompanying the comment with a photo of his fledgling wine collection. While Kirsty’s wine knowledge was more advanced, it’s now a shared interest. They’ve been in their house for nearly two years and continue to work on the renovations together.