If you’re trying to help someone who is obese, it seems logical to focus their efforts on losing weight. But, as Cathy O’Leary reports, perhaps that’s not always the best approach.

If you’re trying to help someone who is obese, it seems logical to focus their efforts on losing weight. But, as Cathy O’Leary reports, perhaps that’s not always the best approach.

Sometimes it doesn’t even take words – it can be a glance or a roll of the eyes. But for the person on the receiving end who is overweight or obese, subtle forms of stigma can be an extra load to carry around.

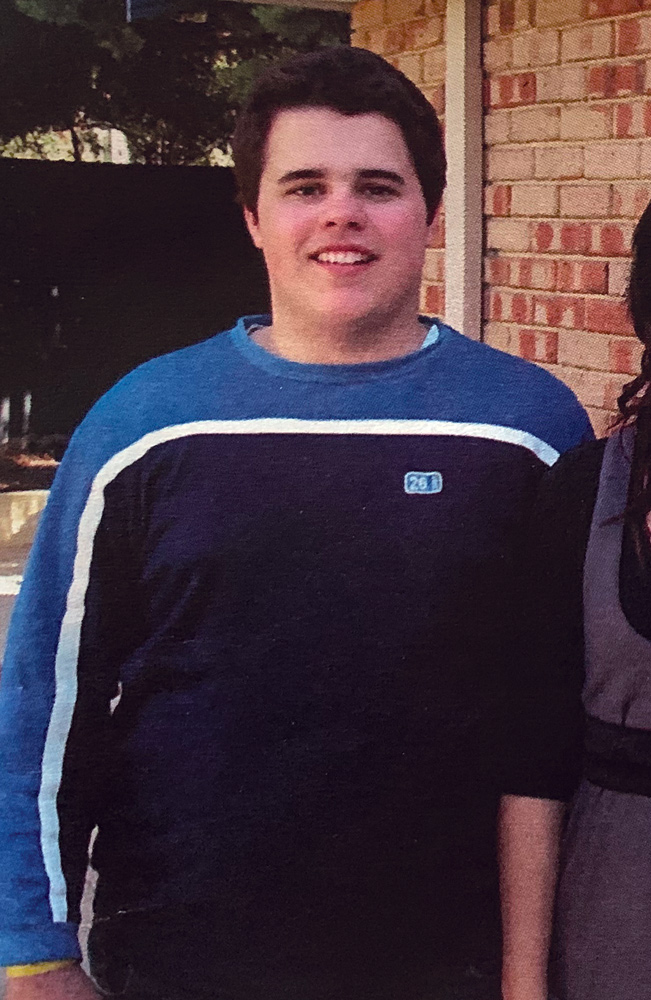

Curtin University School of Population Health researcher Dr Blake Lawrence does not need any lessons in weight stigma. As a child and teenager who battled with obesity, he can remember feeling constantly on the outer.

It became a personal motivator when he and colleagues decided to review more than 40 studies into weight bias among health care professionals and how it could have a negative impact on people living in larger bodies.

Their review, published in the journal Obesity late last year, confirmed weight bias was found among doctors, nurses, dietitians, psychologists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech pathologists, podiatrists and exercise physiologists.

“I was previously somebody living with overweight and obesity, right through my childhood and into adolescent and early adulthood, and can remember distinctly the negative experiences I had in health care settings, and more broadly around the bias and stigma associated with living with it,”

Dr Lawrence said.

If health care professionals had a weight bias, it could make them believe the patient was lazy, less likely to follow their medical advice or had a general lack of care about their health. Some studies, he said, suggested that a weight bias could even negatively affect the care provided by the health professional.

WA’s Health Consumers’ Council has also been active in this area, working with the WA Health Department and the WA Primary Health Alliance – as part of the WA Healthy Weight Action Plan – to unpack how attitudes can alienate people who are overweight.

Weight of numbers

The need for change is clear, with two-thirds of adults and a quarter of children in WA considered overweight or obese.

WAPHA is developing a healthy weight general practice clinical content working group to find better ways to engage with patients, while the HCC recently held an online community forum.

The HCC argues obesity is a complex chronic condition with genetic, environmental, physiological and behavioural determinants. Yet the causes of obesity are often oversimplified to focus only on a person’s behaviours around food choices, levels of exercise or knowledge of nutrition.

In other words, it is easier to label someone who is overweight as lazy, lacking in willpower or non-compliant.

HCC deputy director Clare Mullen said that despite the prevalence of overweight and obesity in WA, it was difficult to talk about, and how people responded was very individual.

While some people were happy to discuss their weight and might even want it to be raised, others found it unhelpful and sometimes harmful.

“One of our consumers who has a daughter with a health condition that makes managing her weight difficult talks about how when she sees health professionals it’s always doom and gloom because her daughter hasn’t lost weight,” she said.

More than weight

“The mother says it’s not just that health professionals want to focus on her daughter’s weight, it’s the fact that she can’t get them to focus on anything else.

“The professionals might argue there’s no point talking about x, y, z until you lose the weight, but the person might already be doing a lot to try to lose weight and they’re not sure what else they can really do.”

Ms Mullen said there was a lot of emerging science around weight health, and while many health professionals believed weight management was part of their scope of practice, very few had specialist training in it.

“Because we all eat and move, many people get a lot of advice from their family and friends – along the lines of ‘have you tried this or that’. I’m not a clinician but having worked in health services for a while, I feel that the more I discover the less I know.”

She said some literature argued that humans were driven to eat a certain amount of protein, and because a lot of it was now wrapped up in ultra-processed foods, our bodies could be fooled into thinking we were getting protein when in fact we were just consuming more carbs and sugars.

And that’s just one strand of the research – there were other factors such as hormones, and the links between mental health and weight gain.

Missing the mark

Missing the mark

That was why glib advice to “just lose weight” often did not hit the mark.

“There seems to be a series of biological mechanisms and we’re still at the bottom of the mountain in understanding them,” Ms Mullen said.

“And some consumers who have been living with obesity since they were children still carry the memories of being bullied at school.

“People in larger bodies say it’s sometimes the non-verbal things, but sometimes it’s the glance, and possibly it’s not even within that health professional’s awareness, but they’re rolling their eyes or looking at you in a funny way.”

When seeing a doctor, perhaps the blood pressure cuff is not big enough for someone’s arm, or the scales do not go above 100kg.

“Much of their life they’re being told, either directly or indirectly, that they don’t fit. Take a chair, some don’t want to sit on it because they’re not confident it won’t break it, or the chair might have arms on it and they couldn’t fit anyway.”

Away from health services, overweight people faced negative attitudes on a daily basis, down to name calling in the street.

“I get so angry because it’s like the last bastion of acceptable prejudice that people can say these comments out loud,” Ms Mullen said.

“And while with some health conditions you can meet other people with the same thing and share experiences, the way we’ve been socialised into thinking about being overweight or obese is to say, “at least I’m not as bad as them” so there is this comparative and internalised stigma.”

Ms Mullen said people with weight issues were not homogenous. The experience of someone who might have hovered most of their life between healthy weight and being overweight and then in middle age had some weight creep on was very different to that of someone who was 150kg and had lived with that for a long time.

“That’s why it’s important we have health professionals who firstly understand enough about the science and secondly have the time and empathy to come to the conversation genuinely interested in finding out what’s going on for that person.

Being overweight might be a filter – not the underlying issue.

“And you need a health professional who will stick with it as long as you, because it can be very tiring trying to do it on your own,” she said.

“And what we’ve also heard from consumers is ‘if you’re going to tell me I’m overweight, I’m kind of hoping that you’re going to be able to help me do that’ because most people don’t need a clinician to tell them that they’re overweight.

“What they might need help with is understanding their actual risk. For someone with a family history of diabetes, weight loss might be particularly important because there are significant health issues, so that might mean looking at weight loss surgery.”

Ms Mullen said that she started looking at this issue back in 2018, HCC did a survey of consumers about weight issues and it really struck a chord.

“Some of the stories were awful – people who had struggled with weight problems for years and just wanted help, but nothing worked,” she said.

“We’re immersed in this idea of personal responsibility and if you’re in that situation of being overweight, it’s entirely your own fault. And not only is it your own fault, it’s because you’re lazy and you don’t look after yourself.”

Weight not the end-all

Weight not the end-all

It was also wrong to assume everyone viewed being heavy as a bad thing.

“Some people might have a body size that puts them in the overweight or obese category, but health and weight is not an issue for them, and then you have others for whom it’s been a major struggle,” she said.

“Consumers want to be asked what it is they have tried and what they think works for them. People think they’re being helpful telling them they should lose weight – but as if that person has never thought or tried to lose weight.”

Ms Mullen said there was a push to change the narrative that ‘fat equals bad’ and promote a more nuanced discussion.

The way people viewed nutrition and eating was affected by many factors, such as grandparents’ attitudes to food and whether or not as children they were told to eat everything on their plate regardless.

“My concern is that if people are making an effort and taking measures to lose weight such as good nutrition and activity, but they don’t in fact lose weight, are they going to potentially stop those behaviours that are still good for them?

“For some people losing weight is never going to be an easy thing, and the motivation required to change habits is significant.

“But I’m excited that there is increasing awareness about weight stigma and its impact.”

Start by asking

The “5 As” model involves a step-by-step framework for realistic and sustainable weight management, with a focus on improving health and wellbeing.

- ASK for permission to discuss weight

- ASSESS weight-related risks and potential causes of weight gain

- ADVISE on weight risks, benefits of weight management and treatment options

- AGREE on realistic goals and expectations

- ASSIST with identifying and addressing drivers and barriers.