This content is part of a paid partnership with Australian Clinicallabs.

Seasonal activity of respiratory viruses is relatively predictable with well-established surveillance systems worldwide to monitor their trends. However, the current COVID-19 pandemic due to SARS-CoV-2 virus, started in late 2019 necessitating unprecedented public health measures to control its spread.

The national 2020 Influenza Season Summary1 found:

- The GP ILI consultations were four times less than the five-year average for the same period (1.6 versus 8.1 per 100 consultations)1.

- Laboratory confirmed influenza notifications were almost 8 times less than the 5-year average (21,266 versus 163,015)1.

- Admissions resulting from confirmed influenza diagnosis to the sentinel hospitals were markedly lower in 2020 compared to the five-year average (15 versus 2,641)1.

MBBS FRCPA D(ABMM)

Dr Sudha Pottumarthy-Boddu has a distinguished career in microbiology with extensive experience in the US New Zealand and Australia. Sudha is a Diplomate of the American Board of Medical Microbiology, and a member of both the Antimicrobial Stewardship Committees and Infection Prevention and Control Committees at multiple St John of God hospitals in WA.

Australia is not alone, with these findings corroborated by similar reports worldwide. United States and other Northern Hemisphere countries, the tropics and also the Southern Hemisphere temperate climate countries have all noted a sharp decline to virtually nil influenza activity in the 2020 influenza season, all temporally related to the implementation of the nonpharmaceutical public health measures2. This worldwide decline in influenza notification, while compelling to attribute causality to these measures, the effect of little travel, vaccination and viral interference have also been postulated2.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) activity also remained low in winter 2020, with sustained absence over a four-month period noted in WA3. School age-children are recognised to play a central role in transmission of both influenza and RSV. Even though schools remained open in WA, the noted marked reduction in RSV detections is thought to be consistent with the absence of a sizeable local reservoir and the true lack of local infections3.

In contrast, a marked change in RSV trends4 was noted in early 2021, with:

- interseasonal resurgence of RSV in Australian children and rise in cases

- higher median patient age, 18.4 months versus range of 7.3 to 12.5 months (P < 0.001; 2012-19).

This change has been attributed to an expanded cohort of RSV-naïve patients, increased number of older children coupled with waning population immunity4.

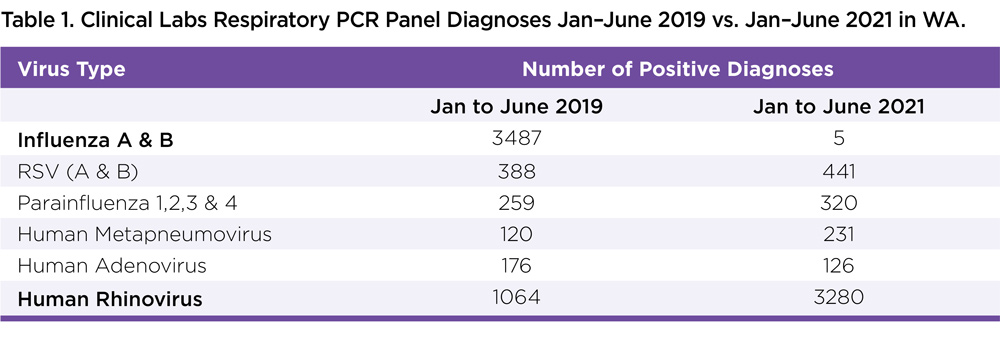

Comparative rates of detections of respiratory viruses by multiplex PCR panel at Australian Clinical Labs in WA during the first six months of 2019 versus the same period this year, are detailed in Table 1.

The notable absence of influenza detections among our test cohort from Jan-June 2021 is unsurprising given similar reports from other parts of the world5. In the Netherlands, the incidence and disease severity in 2020 due to human metapneumovirus was not impacted by the COVID-19 outbreak. 6 Human metapneumovirus is recognised to cause respiratory disease not dissimilar to that of SARS-CoV-2 and is noted to circulate independently6.

The cause of the rhinovirus surge, also noted by others, is unclear7. Rhinovirus spread is driven by children who are more susceptible and immunologically naïve to many serotypes. Additionally, rhinoviruses are non-enveloped viruses, and so less susceptible to inactivation by soap-and-water handwashing7.

The cause of the rhinovirus surge, also noted by others, is unclear7. Rhinovirus spread is driven by children who are more susceptible and immunologically naïve to many serotypes. Additionally, rhinoviruses are non-enveloped viruses, and so less susceptible to inactivation by soap-and-water handwashing7.

The unpredictable nature of the trends of respiratory viral infections in the current winter of 2021 places renewed emphasis on testing for a broad range of respiratory pathogens. This practice has also been advocated by several groups internationally as targeted testing may not hold all of the answers.

Multiplex PCR to diagnose influenza and respiratory viral infections allows for a rapid and accurate diagnosis. This will enable the clinician to initiate targeted treatment early, avoiding inappropriate antibiotic therapy.

Additional clinical tests recommended based on relevant symptoms:

- If you suspect a lower respiratory infection then the appropriate sample is sputum for MCS

- If the patient presents with pharyngitis symptoms then obtain a swab from the throat for culture.

– References 1-7 on request

The author wishes to acknowledge the ACL-WA molecular team led by Ms Dimbi Crogan and Mr Alvaro Defreitas for their unfaltering efforts during the continued COVID-19 outbreak.

Questions? Contact the editor.

Disclaimer: Please note, this website is not a substitute for independent professional advice. Nothing contained in this website is intended to be used as medical advice and it is not intended to be used to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease, nor should it be used for therapeutic purposes or as a substitute for your own health professional’s advice. Opinions expressed at this website do not necessarily reflect those of Medical Forum magazine. Medical Forum makes no warranties about any of the content of this website, nor any representations or undertakings about any content of any other website referred to, or accessible, through this website