After a diagnosis of prostate cancer, many men will turn to their GP for advice on treatment choice. Below is a step-by-step guide to help you achieve the best outcomes for them by asking four questions.

Q1 What is the grade and stage of the cancer?

Patients should have a copy of their pathology report to answer this question.

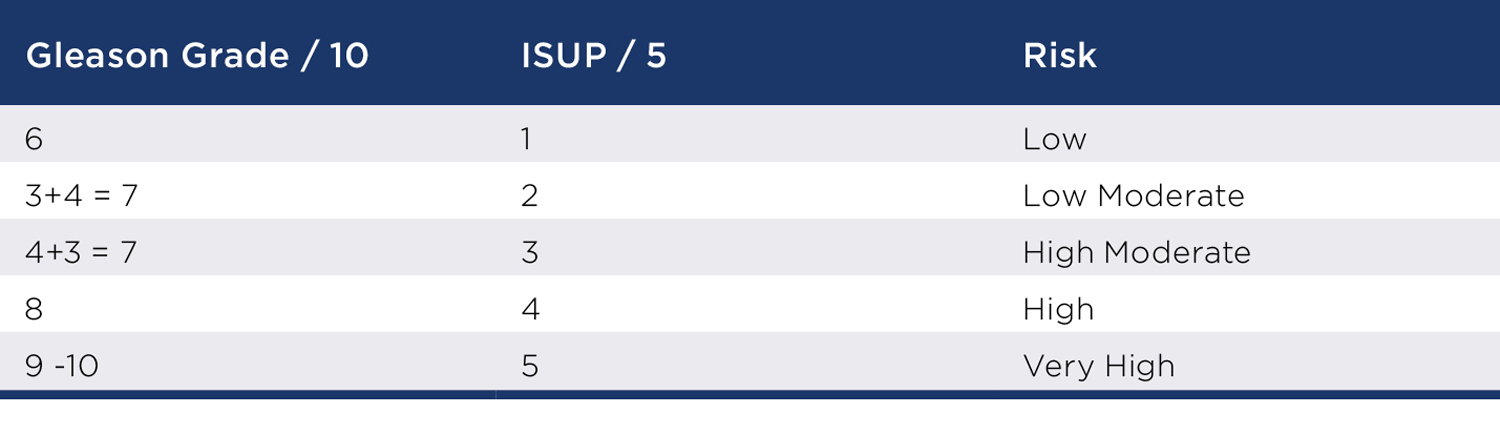

Grade is how aggressive the cancer is. This will tell you how fast it will grow and risk of spread. The Gleason grade is still used, but ISUP scores are becoming more common as they are easier to understand and correlate better to risk.

Stage is how advanced the cancer is and is a function of time. T2 cancers are assumed confined and T3 extend beyond the prostate. To determine nodal and bony stage needs further scans, however, recent advances may still permit cure in more advanced disease.

Q2 Does the cancer really need treatment?

Prostate cancer is the only cancer where active surveillance is commonly practised and this can be a good option for some men. The ProTect study followed men with largely low risk cancers (ISUP 1 and some ISUP 2) for 10 years. Equal survival was seen with treatment or observation, although more bony metastases developed in the untreated group. Older men with medical problems and low-risk disease probably don’t need treatment.

Q3 If we treat, is a cure needed or is control enough?

Cure is desirable when there are more than 10 years life expectancy or with more aggressive disease that is more likely to escape. Cure reduces the need for ADT (chemical castration) and chemotherapy, improving QoL over time.

Surgery – cure is achieved if all the cancer cells are removed, proven by clear margins and an undetectable PSA. Stage, not grade, determines resectability. With accurate MRI staging and robotic keyhole surgery, more cancers are curable.

DXT / ADT – together they achieve control through testosterone suppression and dose dependent radiation induced oxidative tissue necrosis. Devascularisation effects reduce the risk of recurrence and although cancer cells are often still present, durable remissions are expected. Advances in radiation technology can increase dose to target and reduce the dose to other organs. (Image guided IMRT / Cyberknife) Seed brachytherapy has control rates equal to surgery but is only suitable for low to moderate risk disease.

Surgery vs radiotherapy

Surgery vs radiotherapy

If a patient is seeking cure, then surgery is best. They must understand they will have a period of incontinence that is likely to settle with time. Surgery can help incontinence. They will have impotence that requires rehabilitation and may not recover if their cancer is locally advanced. Cure requires no further treatment and men live with normal testosterone levels. Cure is not always achieved, and adjuvant DXT/ADT may be needed. Success is surgeon dependent.

If control is all that is needed or patients wish to avoid incontinence or anaesthetic risks, DXT / ADT should be seriously considered. The ideal patient will have moderate risk disease and be older. Low risk disease can be watched. Overweight patients with significant co-morbidities are more likely to be sent for DXT / ADT to avoid an anaesthetic, but in our experience significant weight loss will correct most of these factors to allow surgery and improve QoL and morbidity long term.

For moderate to high-risk disease there is consistent data showing improved cancer specific and all-cause mortality with surgery over radiotherapy. The average life expectancy of a 65-year-old man is 20 years. About 75% of WA cancers are ISUP2 or more making surgery the treatment of choice for many. QoL is improved by avoiding ADT or chemotherapy, but initial side effects may be worse.

ADT is routinely used for 6-24 months with DXT. Side effects include loss of muscle, central obesity, osteoporosis, tiredness, depression, altered sleep, increased rates of dementia, CV disease, metabolic syndrome and sexual dysfunction. Non cancer death rates are higher if ADT is used. Testosterone cannot be restored after radiotherapy, as dormant cancer is still present.

Radiotherapy side effects include tiredness, radiation cystitis, proctitis (rare with rectal spacing), LUTS, bleeding, second cancers, urethral strictures and erectile dysfunction. Radiation damage cannot be reversed. Local failure is more common in high-risk disease and can lead to ureteric obstruction and renal failure. Additional local treatment is usually not possible. Isolated metastases after local control can be treated, as in surgery.

Q4 Do we have to treat now?

If cure is the goal, yes. If control is the goal, treatment may be delayed in most cases, especially in older men to avoid ADT.

Although a prostate cancer management is highly specialised, the best decisions will come from a team approach. Your understanding of the patient and their goals and life expectancy is a valuable addition to the decision tree. Cure vs control gives us a helpful base from which to make treatment decisions.