One medical condition takes the biggest bite out of Australia’s health spending, but as Cathy O’Leary reports, it’s not cancer or heart disease.

One medical condition takes the biggest bite out of Australia’s health spending, but as Cathy O’Leary reports, it’s not cancer or heart disease.

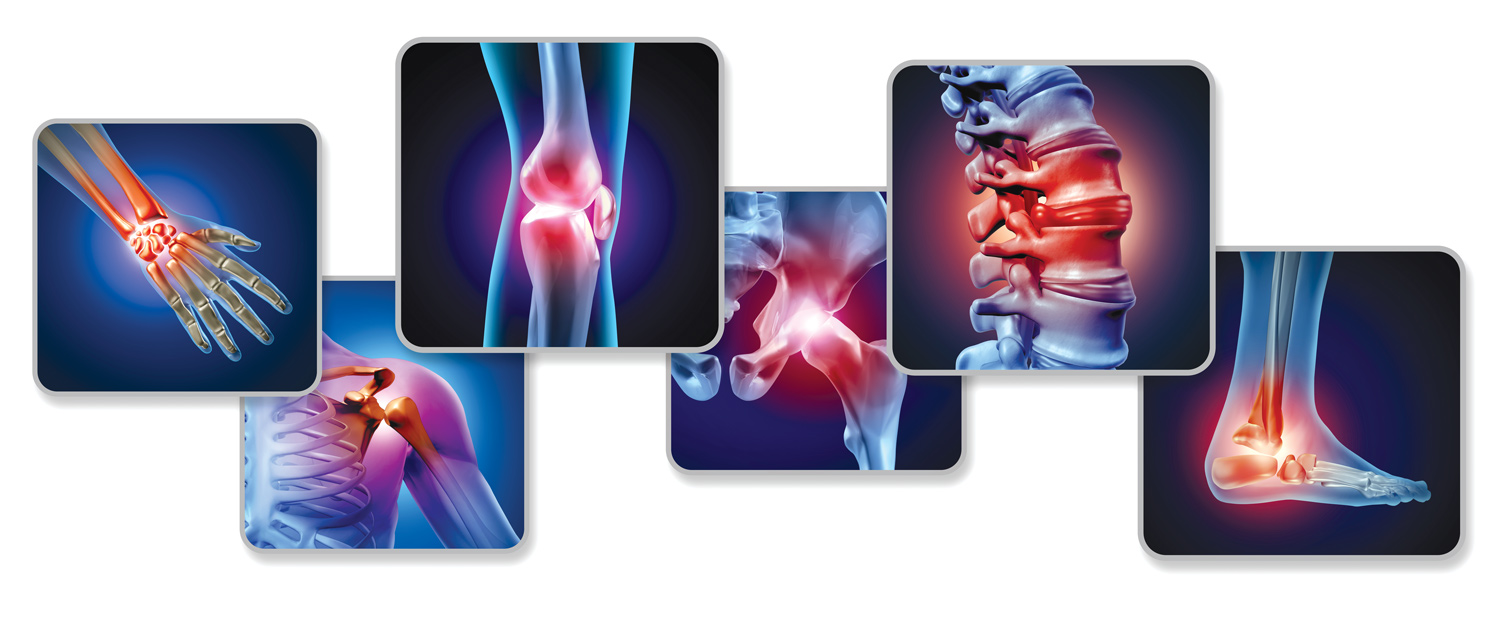

Musculoskeletal conditions are crippling in more ways than one, breaking not just bones, but also the bank – to the tune of $14 billion a year in Australia.

A newly-released report from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare found that more money was spent on musculoskeletal disorders such as osteoporosis and back pain than any other disease, condition or injury in 2018-19.

Bad backs, big bucks

Of the $136 billion spent across the entire health system that year, musculoskeletal disorders consumed the most dollars, followed by cardiovascular diseases ($11.8 billion), cancer ($11.8 billion), and mental and substance use disorders ($10.5 billion).

A separate report by Musculoskeletal Australia, based on a national survey last year, recently revealed that of the seven million Australians with a musculoskeletal condition, 93% said it had a significant negative impact on them.

More than half reported their ability to carry out basic daily activities such as cooking and grocery shopping was affected by their condition, and almost-three quarters said it badly affected their sleep.

And Musculoskeletal Australia predicts it will get worse, with the number of people living with one or more musculoskeletal condition expected to grow to 8.7 million people by 2032.

Its CEO Rob Anderson said musculoskeletal conditions already affected a staggering one in three Australians, often seriously impacting on their daily lives.

“This report reveals why so many are crying out for compassion, for understanding, for change, and the survey data now provides us with the opportunity to offer more support,” he said.

Global push

Meanwhile, a new global effort involving Perth experts aims to put musculoskeletal conditions firmly on the map in terms of government awareness and funding.

An international research team found that despite being the world’s leading cause of pain, disability and healthcare costs, the prevention and management of conditions such as low back pain, fractures, arthritis and osteoporosis remained under-prioritised.

In response to a call by the Global Alliance for Musculoskeletal Health based at the University of Sydney, the team has identified key areas for improvement, including better access to medicines and technologies and more health care professionals working in the area.

Project lead Professor Andrew Briggs from Curtin University said that globally more than 1.5 billion people lived with a musculoskeletal condition in 2019, which was 84% more than in 1990. Despite many calls to action and an ever-increasing ageing population, health systems continued to lag behind treating these conditions and catering for their rehabilitation needs.

Invisible conditions

He said musculoskeletal disorders were not on the radar because they had a lower profile compared to other areas of medicine and were not commonly linked to death. Therefore, the presumed significance and societal relevance was considered to be lower.

“But when you think about people having to live a long time with pain and disability, that’s also important,” Professor Briggs said. “Death is tragic of course, but living in chronic pain and not being able to work or go to school, that’s equally problematic to society.”

He said many policies and funding were directed at conditions such as cancer, diabetes and heart disease, while musculoskeletal disorders languished.

“Costs for cardiac disease are obviously high but typically episodic and in tertiary hospitals, whereas musculoskeletal conditions go across primary, secondary and tertiary care,” he said.

“And when you scale up the cost by the number of people who have musculoskeletal issues, then it’s enormous compared to a smaller fraction of people that might have big costs but the net cost is much less.”

While some conditions such as osteoporosis and osteoarthritis were more common in older age, autoimmune conditions such as juvenile arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis occurred much earlier in life and were life-long.

“So, this idea that musculoskeletal diseases are an inevitable part of ageing is inaccurate because they can be lifelong and occur in children aged as young as five,” he said.

“We’re trying to take a system view rather than a clinical one, so you have to consider financing, workforce, policy and service models, or in other words what needs to be done at a macro level to address this huge burden.”

Professor Briggs said that while there was a pressing need to put musculoskeletal health care on the global map, there were varying levels of care and resources between low, middle, and high-income countries.

“One of the limiting factors to reform efforts is that no global-level strategic response to the burden of disability has been developed until now,” he said.

While WA led the world in policy and strategy for coordinated care for musculoskeletal conditions, he said it was disappointing the conditions were not a focus in WA’s Sustainable Health Review, given the data was clear that it was the leading cause of disability in Australia.

Hip fracture registry

Hip fracture registry

In other moves to improve how musculoskeletal conditions are managed, Perth doctors have helped develop the world’s first hip fracture registry toolbox to improve care for the more than one million people in Asia Pacific who fracture a hip each year.

Developed by the Asia Pacific Fragility Fracture Alliance and the Fragility Fracture Network, the practical resource explains to other countries how to advocate for a national hip fracture registry.

One in four patients who sustain a hip fracture die within a year, and less than half of those who survive regain their previous level of function.

Tailored to clinicians, hospital administrators, healthcare systems and governments alike, the toolbox shows how to set up a registry, including getting ethics approval and patient involvement.

Fiona Stanley Hospital consultant geriatrician Dr Hannah Seymour, who among her many roles is co-chair of the alliance’s hip fracture registry working group, said WA had been leading the way for some time when it came to hip fracture care through its tertiary hospitals and coordinated geriatric services.

“A national hip fracture registry has been going in Australia for five or six years, and WA has been performing quite well,” she said.

“But we can always do better, given the epidemic of osteoporotic fractures, and hip fractures are the most common types that come into hospital.”

Proactive care

Dr Seymour said the registry aimed to measure and improve clinical care, such as time it took for patients to receive analgesia in emergency departments. The toolbox was to help other jurisdictions learn from places like WA and develop their own models of care.

“For some hip fracture patients, it’s about fixing them and getting them back to full independence, and then there’s a group in the middle who are frail older people at home and the aim is to get their lives back to as close as possible as it was before.

“And then we have very frail patients coming from residential care, and some have dementia, and the reason we’re fixing hips is mainly for pain relief, and generally they do poorly.”

Dr Seymour said a hip fracture could be life-changing for many people, and prevention was key so that they did not become a statistic on the registry.

“An important message is to treat osteoporosis before someone has a hip fracture, so when people come in with a wrist or humoral fracture, there needs to be a path to treat their osteoporosis so they don’t end up with a hip fracture.”