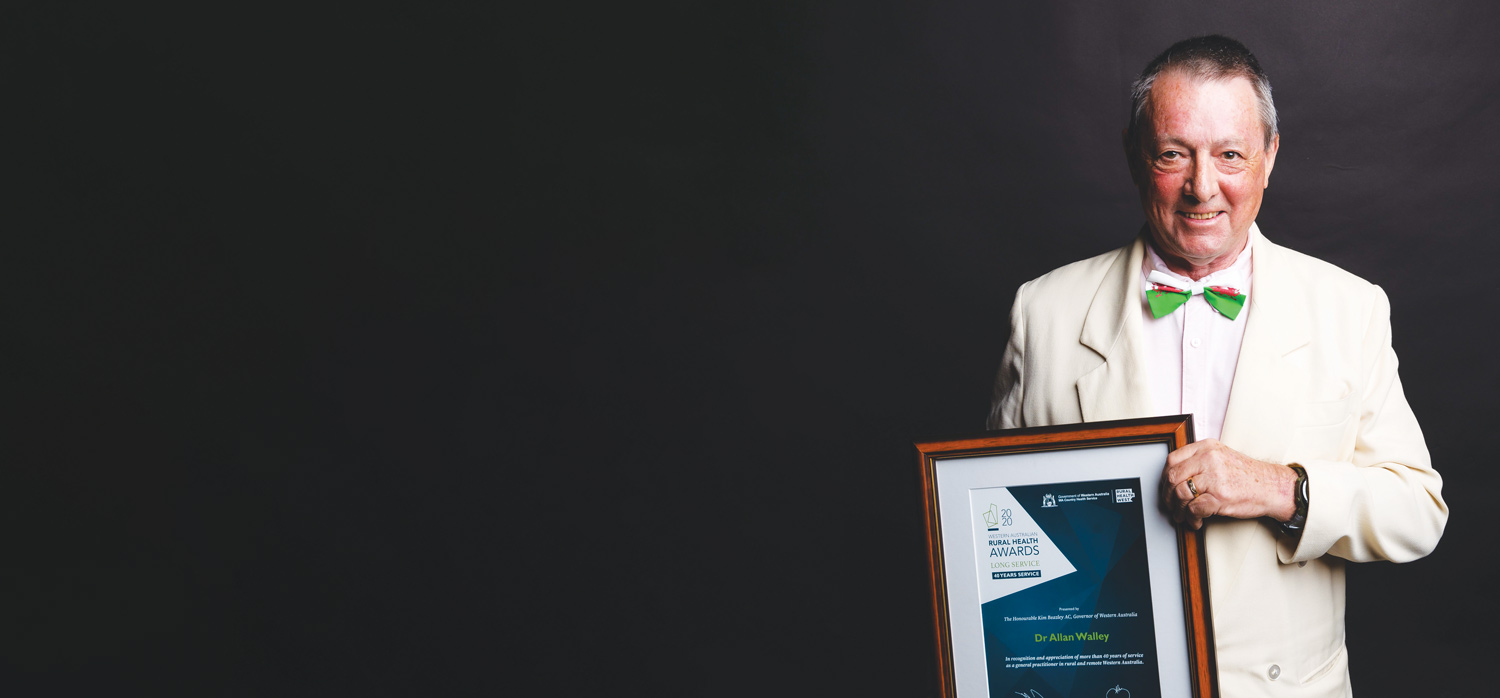

A country boy at heart, semi-retired GP Allan Walley tells Cathy O’Leary why rural life has always suited him down to a tee.

A country boy at heart, semi-retired GP Allan Walley tells Cathy O’Leary why rural life has always suited him down to a tee.

After 40 years working across the A to Z of Western Australian towns, Dr Allan Walley has had plenty of time to reflect on what makes rural doctors a breed apart.

The 74-year-old believes it is because they are part of the community. He remembers walking around small towns in the early days, when he knew everyone’s name and even the name of their dog.

The 74-year-old believes it is because they are part of the community. He remembers walking around small towns in the early days, when he knew everyone’s name and even the name of their dog.

“When you work in rural areas, within a fairly short space of time people get to know who you are, and they can relax and let you know what’s really happening in their lives,” he says.

“Once, when I was going away, one of my patients said to me, ‘I’ve only ever had one doctor, what am I going to do when you go away?’”

That’s part of the reason he has continued to do locum work after retiring from full-time work at his practice in Margaret River and Augusta in 2013. He knows first-hand the importance of having doctors who can step in when country doctors need a break.

“I felt I didn’t want to work full-time anymore, but I still enjoy my medicine, so the locum work fulfils me too,” Allan says.

Born and raised in Bangor, North Wales, Allan was a teenager when his family migrated to WA, and he started studying medicine at the University of WA in 1968.

His first taste of rural medicine was a six-month stint working in the Amazon Basin in Peru, just 15 months after graduating. He worked there for six months, taking a trusty obstetrics book with him which guided him in delivering dozens of babies, as he gained experience in using forceps, manually removing placentas and delivering by caesarean.

WA all over

WA all over

Allan moved to Augusta in 1979 and worked at the medical clinic in town for five years before working on Christmas Island from 1995 to 1999 and joining the Rural Health West roving locum team in 2000, before returning to work in Augusta and Margaret River in 2003.

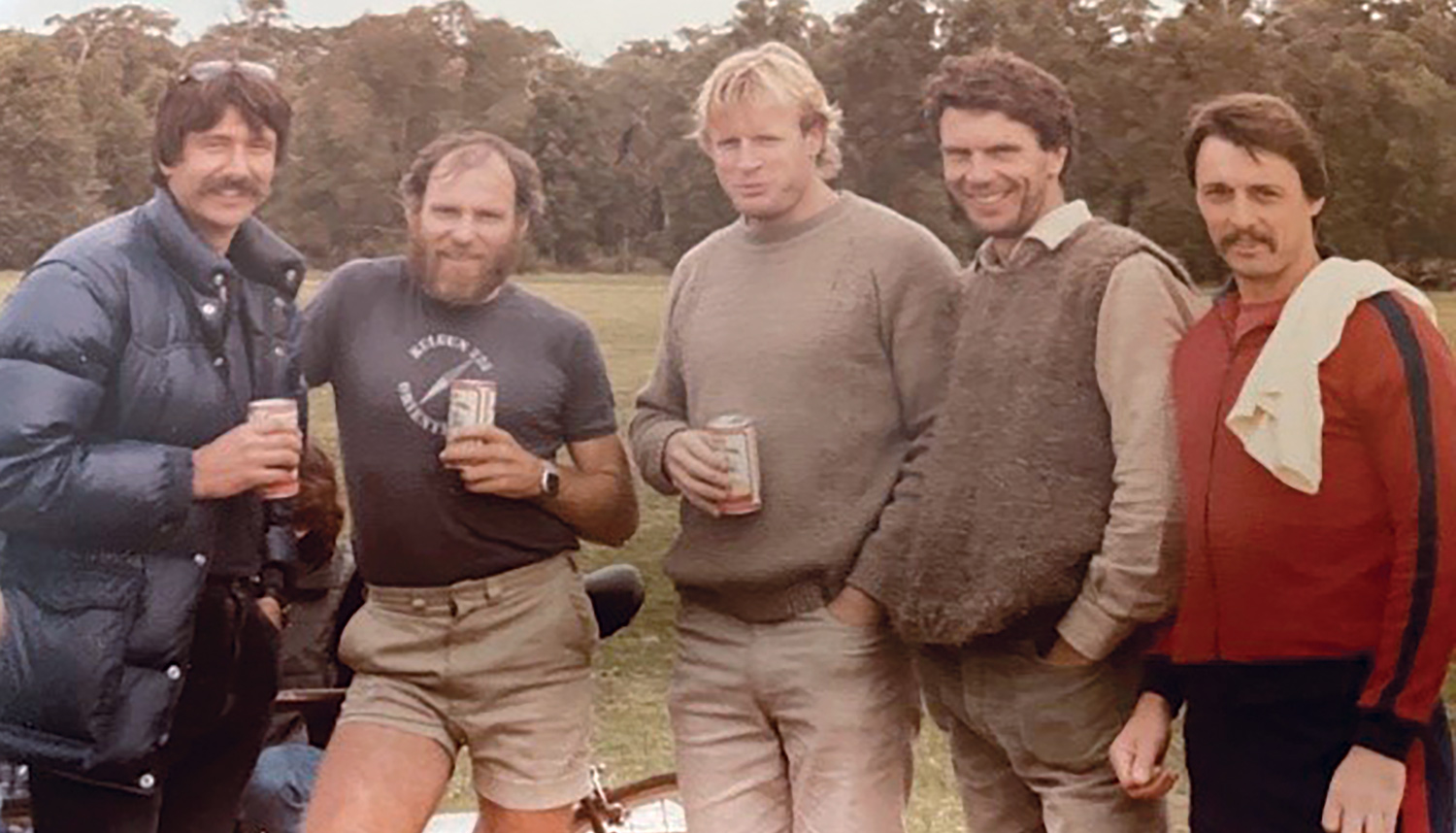

In his younger days he was a commercial diver and took part in several expeditions with the Maritime Museum to Augusta and Thailand, serving as the medical officer. And in recent years he has visited Broome to carry out commercial dive medicals for the pearl drivers.

Not surprisingly, he was Rural Health West’s Rural GP of the Year in 2011.

Because he was born and bred in the country, he feels at home there rather than in a big city and dismisses the notion that country doctors can become too involved in the lives of patients. He firmly believes friends are your patients and patients are your friends.

“Because I was born on a farm in a little village, and I was used to everyone knowing everyone, to me medicine was medicine, so what happens inside the surgery happened in the surgery, and what happens outside it is something different,” he says.

“I’ve always been very comfortable that.

“When I worked on Christmas Island, once one of my friends who was also obviously one of my patients said to me, ‘oh god how do you cope with seeing patients in the surgery and then seeing them socially and having fun with them afterwards?’ and I said ‘well, it’s the way I’ve always been… what happens at work stays at work.

Drawing a line

Drawing a line

“But it wasn’t like I was Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde because when I saw them at work, they were still my friends as well as my patients. It’s just about drawing a line. I put my professional cap on and switch into that mode, but they can still be your friends.”

There is an emotional downside, he admits, when your friends (and patients) get old and die.

“That is difficult. You grieve, and that’s never comfortable, but you still have to do your best with the scenario that’s before you. It’s not that you harden up, but you have to adjust and do your job.”

He found it relatively easy to slip back into the role in his locum work as needed, particularly as most practices make sure he has a good set of notes on patients.

“The fact that it’s computerised makes a big difference and makes life a lot easier – even though it was challenging for me because computers weren’t even invented when I was doing my training,” he says.

But he laments some changes in rural practice that he has seen in his later years.

“One downside is that in places like Augusta we used to do a lot of minor operations, and we did anaesthetics for the visiting surgeons, and we delivered babies – we did the whole lot but now none of that happens there.

Changing times

Changing times

“The bureaucrats said, ‘no you’re too isolated’ and in inverted commas ‘you don’t have the skills’ which of course we did.

“You learned to manage things well and pick things early that needed to be transferred. In the 40 years that I’ve done medicine, we never lost a baby, never had an anaesthetic incident and never lost anyone in theatre because you learnt to predict so well. But now it’s not done like that, they just say your hospital’s too small so you can’t do it anymore.

“I’d been delivering babies for 10 years, and I had a diploma in obstetrics and gynaecology as well, and I hadn’t had any incidents, and yet I had to justify why I should still be allowed to deliver babies.”

Allan says the birth of a baby is always an exciting moment and that excitement never leaves you.

“One of the things I love to hear is the baby crying because it means the baby’s OK,” he says. “People forget that. They want these quiet births, but a baby crying is a beautiful sound and very reassuring.”

ED: For more on what’s happening in the State’s rural medicine landscape, watch our for our special publication, Going Bush, which will be arriving in your mailbox in early June.